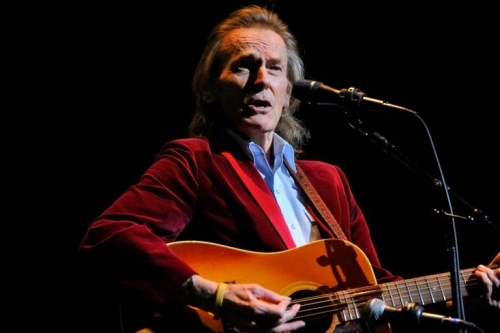

Plans of His Own – The Gordon Lightfoot Interview – Part 2

Listen to part two of our interview with Gordon Lightfoot above.

Part one can be found here.

Gordon Lightfoot walks in on a young Bob Dylan hunkered over a typewriter, the poetry of his renowned lyricism passing through his fingers and onto the keys to be imprinted in ink on paper. They will either be used or jettisoned. We’ll never know. It was a pretty prolific time for both of them.

You could picture Dylan there, disheveled, a wisp of smoke rising from the collection of crushed out cigs in the ashtray beside him, hammering out his lines while Lightfoot stood dumbfounded by the man's ability to type.

Bob, perhaps without missing a keystroke, turns and, through the smoke, speaks in a voice that can only belong to him: “What, Gord, you never learned how to type in high school?”

Lightfoot retorts with the first thing that comes to mind: “Well, Bob, I took Latin lessons.”

Bob may have grinned, he may have grunted, but he most certainly kept on typing. As I said, it was a pretty prolific time.

The year is somewhere around 1964 and Bob’s about to blow the roof off the folk revival by going electric. Lightfoot may have very well been bearing witness to the genesis of lines that would form Dylan’s lyrical rock revolution.

How does it feel

To be on your own

With no direction home

Like a complete unknown

Like a rolling stone

How did it feel, I wonder?

This is the mid-60s. This was Woodstock, New York, a couple of years before half a million strong would descend upon Yasgur’s farm forever transforming the little town into a moment that would define an era. For now, though, Woodstock wasn’t a festival. It was a colony of creativity where one could have painted one of those music icon assembly posters and it’d have actually been a reality. Along with Gordon and Bob, people like Janis Joplin, Simon and Garfunkel, Hendrix, George Harrison, Eric Clapton, Van Morrison and the Band would all pass through at some point.

Bob and Gordon would carry a mutual respect for one another all their lives and when asked Lightfoot wouldn’t hesitate in saying Dylan was his favourite musican but it all started there. Lightfoot was writing songs that would become hits for others at the time while working on his first album. It would be released after his buddy Bob hammered a few nails into the coffin of his time revitalizing the folk scene. Those days were gone and soon so would go Woodstock. There would be a motorcycle crash, those world-shattering new recordings and a man who was already a star would move out of his shimmering corner of the universe into the galaxy of legend.

Gordon had a few years to go but he’d get there. 16 Juno Awards, 4 ASCAP song writing awards, five Grammy nominations, Canadian recording artist of the decade. He was inducted onto Canada’s Walk of Fame in 1998, made a celebrity captain of the Leafs, given the Order of Ontario to go along with the Order of Canada. Heck, they even sculpted him out of bronze in his hometown of Orilla. It was only fitting when, in 1986, Bob got to induct Gordon into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame.

Still, with all the accolades and trophies and plaques, Gordon shy’s away from acknowledging what his music has meant to his country. He doesn’t really consider himself a legend, Canadian or otherwise, just a guy with a guitar and a few words to sing. When asked what his most cherished award is he mentions certificates he won singing for the Kiwanis club. This was before meeting Bob, before Woodstock, before even writing his first songs.

Gordon was only 13.

Now in his twilight years, he looks to his youth and, like Charles Foster Kane in the famed Welles film, he holds tightly to the memories of growing up. Lightfoot’s Rosebud would be Massey Hall.

"There I was 13 years old and singing a solo," says Lightfoot still sounding astonished by this moment, as though it were only last week and not over five decades ago.

Though illness has threatened to take him out a few pieces at a time, thankfully, the memory remains. He'd later play there dozens of times but, as a kid, it was where he first got a taste of what could be.

There was no other way to go. A few deviations, yes, but he would be a musician, and, whether he likes to admit it or not, that once 13-year-old kid on the Massey Hall stage would become a legend.

Unlike at least one of his contemporaries, however, he'd become a legend with Latin lessons.

In the second part of my chat with Lightfoot we’ll touch upon his illness and how he overcame it only to come full circle, returning once again to his youthful memories where he's still a kid singing Christmas tunes on his relative’s kitchen table.

Ottawa Life: Many don’t expect such a drastic curve to be tossed their way so late in their career but, in 2002, you were standing at the start of what would become a bump filled road ahead of you for a few years. A few newspapers, if I recall correctly, even proclaimed you hadn’t survived. How did that affect you? I read you were having visions of your own death for a while?

Gordon Lightfoot: That thing lasted for 19 months altogether, from start to finish, but for the first six weeks I don’t remember anything. They played music for me to make me wake up and the very first tune I heard was one of my audience’s favorite tunes, “Minstrel of the Dawn”. It was the first thing that I finally heard coming through that headset. So for the next several months I recovered from the multitude of operations that I had and started working on some demo recordings. I got the guys into the studio and we made another album.

I wondered if I would ever be able to perform again. I tell you for awhile there I wasn’t sure. Then I started to get the feeling that I would be able to the second or third time around going back into the hospital for more rounds of operations. I mean, this thing was something else!

I practiced all the time, when I was home and healing, just practicing the guitar. I think I learned things about the guitar that I didn’t know. We wound up getting a pretty good album out of it. By the time it was all over with it took fourteen months to work on that album while I was going through this whole process and I never thought of my condition at all. I thought how fortuitous it was that we had some raw material that we could work on.

You said you learned new things about the guitar. As somebody who playing must have seemed like second nature by that point, losing feeling in your fingers must have had you having to approach the instrument differently. What were some of the things you did to keep in form?

What happened next, well, we lost our lead guitar player. He died. Terry Clements, one of my very best friends and it almost brings tears to my eyes. He worked with us for 40 years. I brought him into the band with (Laurice) "Red" Shea when he had to leave the road. Terry was a wonderful guitar player. He got into some health issues and he died at an early age of 63 years old. During that time we brought in a replacement and this guy brought in a tuning system, an idea for me to get better tones out of my instruments because my tuning has never been 100 per cent. Now I had a guy who comes along who had perfect pitch and he shows me what to do. We take the guitars to a technician to get work done that I’d never think of doing and suddenly these guitars are getting easier to tune. By doing this we were achieving about 30% more volumn and the sound is a lot cleaner also. We’re getting into some of these places and the people just love it.

Certainly nobody would have blighted you had you decided to retire. I’ve seen you perform twice in recent years. For a guy who’s taken the toll you have your energy still comes out powerfully in the performance. What continues that drive in you to perform?

This is the truth: I exercise every day. I’ve been doing that since 1982. It’s impossible to keep up and yet I’ve been doing it. The older I get the more I do it. That is what is giving me my stamina, my strength, whatever it is. I feel that way when I am up there. I feel strong. I don’t get tired but I have to do that workout every day. I don’t do it in my basement or living room, either. I have to go to a gym. I’ve been going there ever since I gave up alcohol back in ’82. I tried working out about three years before I quit but trying to go in with a hangover wasn’t a great thing. When I gave up alcohol I got into a pretty serious regiment.

That’s a pretty good trade off, alcohol for exercise.

Absolutely! I could never do it with the amount of strength that I do without the exercise. It’s a routine.

You’ve been pretty modest when asked about how you feel your music has shaped this country. We know what your music has meant to Canada but what, do you feel, has Canada meant to you and your music?

Well I got a lot of good ideas about Canada when I was up canoeing in the North. A lot of wonderful landscapes come to mind up above the boreal forest. Landscapes often come into it as backup to a song when I am using my imagination. It’s kind of odd, like background music in a movie. I would get ideas while watching sporting events and practicing my guitar. When you’re under contract, which I was for 33 years, you’re thinking about song titles. For example, the song “Early Morning Rain” was “Early Morning Train” and then I thought there were too many songs about trains on that record.

Another musician that has meant a lot to Canada is Gord Downie. What were your reactions to his announcement this year and him and the Tragically Hip pursuing one final tour?

I know one thing for sure is that he had already had one operation about 11 months ago. I did a show with Gordon for the CBC and it was some of the most fun I’ve ever had. When they were doing their last tour I was afraid I wouldn’t get to see them at all as they were on the road and we were doing our trip. As fate would have it we were playing in a Casino down in Moncton and just as we got off stage we knew their show on CBC was just coming on. So we raced up to the hotel room and watched the whole show from Kingston. It was an experience, watching how that show was done.

Looking to your coming show here at the NAC, can you share a memory about times performing there?

Well, it was 1967 and the place had just opened and all I had was my trio. I had "Red" Shea and John Stockfish and we walked out and played in that place and I was amazed. It was the first night or first week but it was brand new. It was Canada’s 100th birthday. At that time I was not even a confident performer. I still got nervous and felt I was inadequate musically. I got that cured later on.

It’s got to be interesting coming back now for Canada’s 150th. The place has had a bit of a makeover.

Well, I’ll be able to see it from point A from point Z. They’ve told me about this and it only makes me curious.

Over your career you have amassed many awards and accolades but, looking back, what have you personally found the most rewarding aspect?

I don’t know, I think maybe it could be the certificates that I won at the Kiwanis Festivals when I was 13. That was the first time I played in Massey Hall, singing the solo there because I won my class in the second year.

It’s kind of like your Rosebud.

Yeah, I mean, it was a long time before I played there again but there I was 13 years old and singing a solo. My parents loved Bing Crosby and I’d ask my mother if he makes a living doing this. I wanted to make a career out of it even then. I wanted to be a professional!