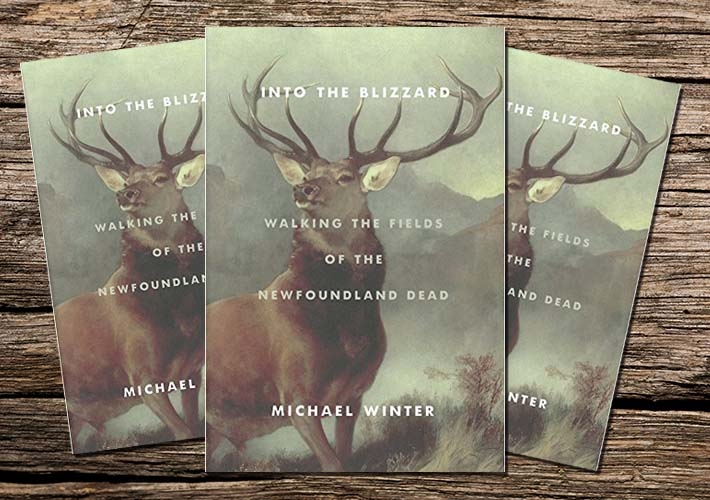

Into the Blizzard: Walking the Fields of the Newfoundland Dead

In October 1914, 537 young men from Newfoundland boarded the Florizel, the ship that would sail them across the Atlantic and towards the battle shores of Europe. The Great War had started in August of that year and Newfoundland’s governor had offered England this small contingent of soldiers. As a British Dominion – Newfoundland was still decades away from joining Confederation–this sort of contribution was expected. After ten days at sea the Newfoundland and Canadian regiments with whom they travelled would dock at Devenport, England. Other contingents of Newfoundland soldiers would eventually follow. Their first and for a time only experience of war was of the tediousness and often severe loneliness of training. That would change when they were called to fight in what would become some of the war’s great theatres of battle, Gallipoli, the Somme and Beaumont-Hamel, among others. By the war’s end in 1918, approximately 1300 young Newfoundlanders would lose their lives in the fighting. That number would be unexpectedly, devastatingly high.

Indeed, as Michael Winter discovers in his moving book, Into the Blizzard: Walking the Fields of the Newfoundland Dead, one of the most striking features of the Great War was the disconnect between everyone’s expectations and the war’s grim, horrific realities. Young men from Newfoundland enlisted seemingly in the spirit of fun and adventure and with every expectation that the whole enterprise would be short in duration. They would be home soon. No one had any inkling what lay in store for them. Parents of soldiers apparently thought no different. Families gathering at ports to see their sons off did so more in a mood of jubilation than foreboding. Only slowly did the horror of what was to come alter the community’s perception of war. Winter describes how one mother sent her son a parcel of socks, as though cold feet was the most dire hardship the young man would experience. When told that the son in question was dead, she asked that the socks be then given to her other son in the army. The mother’s response had both naivety and stoicism in equal measure.

Winter sets out to better understand the experience of Newfoundland’s young soldiers. He does so by flying to Europe and then traversing some of the same territory in which Newfoundland’s Royal Regiment found themselves. He bicycles to Beaumont-Hamel, Auchonvillers and Les Galets. He attends ceremonies honouring the soldiers of the Great War. He seeks out cemeteries containing the fallen. The result is a book that’s hard to classify. It’s at once a sort of memorial to all the Newfoundland men and women who fought in the Great War and a meditation on war itself. It’s also something of a personal traveling memoir.

There is a deep ambivalence running through Into the Blizzard. The ambivalence is expressed not so much in the questions Winter asks but in the thoughtful, searching answers he gives. How should those Newfoundlanders who enlisted and fought be remembered? How should they be memorialized? How should we understand the relationship between this chapter of Newfoundland’s past and the present?

Tracing the territory Newfoundland soldiers traversed and the places where the fiercest battles were waged and the greatest losses of human life occurred is, of course, meant as an act of memorial. The decision to walk through former theatres of war is also what gives rise to the book’s chief strengths. Winter is most effective when he finds himself in say, Salisbury, and casts his mind back to 1916. He employs seemingly the most innocuous type of activities as portals to go back in time. Kicking a soccer ball on the fields of Salisbury reminds him that Newfoundland soldiers in training likely engaged in the same sort of fun. Writing post cards to his wife and kids allows him to picture soldiers doing precisely the same thing.

More importantly, it allows him to imagine the nightmare in which those young men just beginning their lives were thrust. The lush fields of Gallipoli in which Winter himself stood were fields of slaughter and unbearable suffering during the war. The juxtaposition is meant to be jarring. For here in 1916 is where soldiers were introduced to trench warfare and the many hazards it wrought. Trench foot, dysentery, flooding: all were experienced by the soldiers living and dying in the trenches. Here in Gallipoli and the places of subsequent battles–at the Somme, for example – is where soldiers were forced to walk into a ‘blizzard’ of bullets and artillery. Nearly entire regiments could be mowed down in a matter of minutes, as was the case in Beaumont-Hamel. Winter honours their courage but laments the obscene waste of so much life.

The suffering soldiers endured, moreover, was not always inflicted by the Germans or the Turks. Winter tells the story of John Roberts, a 20-year-old soldier who in 1916 walked away from his regiment while stationed in France. When he was found a few months later he was charged with desertion. His punishment was to be blindfolded and then executed by a firing squad. Robert’s sorry end speaks to the tragic absurdity of the conditions into which all of these young men were unwittingly pushed and hopelessly unprepared. As Winter suggests, he was not simply afraid; Roberts was likely suffering from post traumatic stress disorder. But the army did not understand, let alone tolerate, any such afflictions. They were treated as signs of personal weakness that, left unchecked, would threaten the entire regiment and by extension the entire war effort. Winter uses Robert’s story as an important antidote to the sort of jingoism he takes pains to avoid. In honouring Newfoundland’s fallen, Winter is also insisting that war constitutes a type of madness that destroys and deforms the men sent to fight. Although hardly novel, this remains a vital insight in a world that remains so rife with conflict. Think Syria and Iraq.

The connections between the past and the present is never far from mind for Winter. One problem, however, is that those connections are not always evident, particularly when Winter refers to his own experiences. In one instance he talks about his family’s purchase of their new home in Toronto and the decision to renovate. The reader is left scratching his head. For there is no connection between the author’s home improvements and the book’s larger theme. On the contrary, that sort of discussion is too far removed from the idea of tracing the steps of Newfoundland soldiers fighting in the Great War–and is perilously close to self indulgent. There are other such moments in the book. Into the Blizzard , for this reason, works beautifully as a meditation on Newfoundland’s experience in the Great War but not very well as a memoir.

All of the young Newfoundlanders who fought in the Great War are now gone. Hundreds were buried under the ground that a century later Winter himself walked on in preparation to write this book. So much of what he writes is meant to evoke their memory and shed light on their respective legacies. To great effect, he recalls individual soldiers’ particular stories. We learn of Alexander Parsons, a soldier who was sent to Quebec in 1916 after contracting pleurisy and then returned to Europe’s battlefields in 1917. He survived and, in 1921, returned to Newfoundland and opened a family cabinetmaking business.

Other legacies are perhaps harder to discern, but no less profound. Winter shares Cyril Gardner’s story, a soldier responsible for capturing seventy Germans, but who was later killed at the Battle of Arras in the spring of 1917. When the German prisoners were handed over to the British he made sure all their lives were spared. If any Germans were killed, he declared, those responsible would be killed themselves. The Germans awarded him the Iron Cross. Gardner’s legacy is the memory of he retaining his humanity amidst so much carnage. Like thousands of his fellows soldiers, he did Newfoundland proud.