Remembering the Politics of Fear

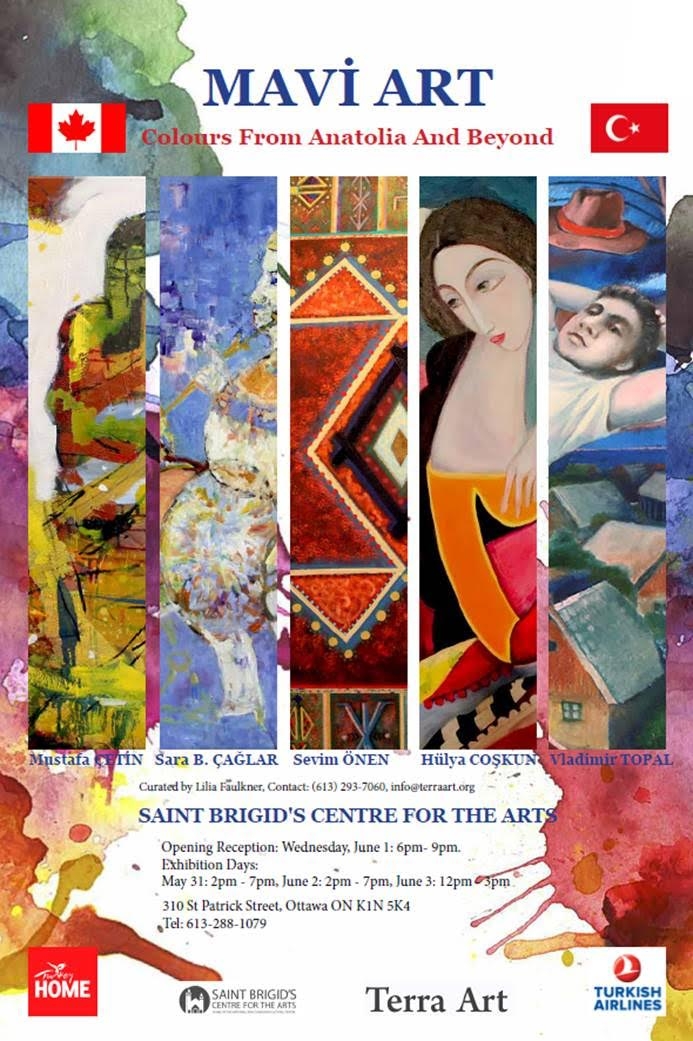

The recent debate over the admittance of Syrian refugees is ominously reminiscent of events that took place over a century ago in Canada. Indeed, Syrians were among the hundreds of thousands of immigrants who entered Canada, aggressively recruited by Canadian government agents and their proxies throughout Europe, the Ottoman Empire and Asia to facilitate unprecedented economic growth between the years 1896 and 1914. Despite the numerous challenges inherent in the migration process, these newcomers embraced their new surroundings as settlers on the prairies, labourers in urban factories or industries on the Canadian frontier and established communities in the process.

When war broke out in the summer of 1914, Syrian loyalty to the British Empire was without question. They immediately contributed $525.00 to the Canadian Patriotic Fund in September, 1914 and established a Syrian Home Guard company with the intent of gaining recognition from the Militia Department and eventual attachment to the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Indeed, community spokesperson and businessman J. Aziz explained their sentiments in Toronto’s Globe, “We are not Turks and resent being called Turks. We, Christians, have been deprived of civilian and religious rights in Syria… we Syrians fully appreciate the freedom with which we are permitted to live and trade in Canada, and interference with the Dominion and her trade means interference with us, and that is why we want to express our loyalty.” The federal government duly recognized their contribution to the war effort.

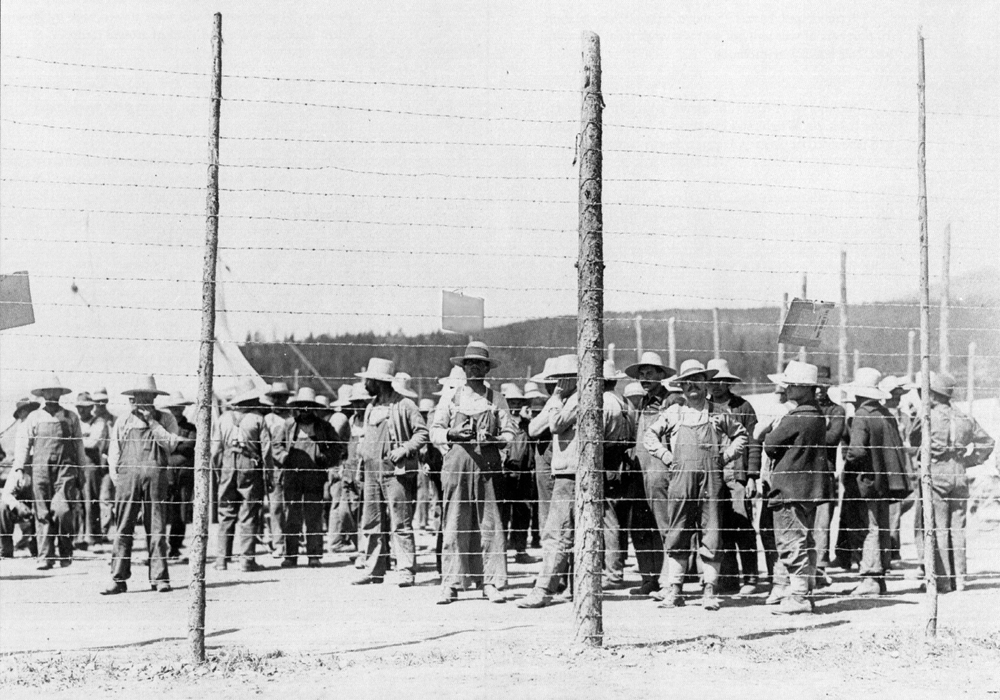

However, things would soon change. Turkey’s declaration of war against Great Britain in November of 1914 did not concern Syrian-Canadians as they were resolute in support of the Entente Powers that included Great Britain, France, Russia and the United States among others. However, the Canadian government utilized its broad powers under the War Measures Act and suddenly ordered all Syrians to register as enemy aliens in early 1915. They joined approximately 80,000 other subjects of Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria in Canada that had to report to authorities as required and were denied their civil liberties for the duration of the war and beyond. Syrians, along with 8,579 persons that included Ukrainians, Alevi Kurds, Armenians, Bulgarians, Croats, Czechs, Germans, Hungarians, Italians, Jews, Turks, Poles, Romanians, Russians, Serbs, Slovaks and Slovenes, of which most were Ukrainians and civilians, were deprived of their personal property and became prisoners of war in a network of 24 internment camps established across Canada. They were used as a cheap source of labour by the government and commercial interests and some remained imprisoned until early 1920. Over 100 internees died while in custody.

The Canadian government’s policies regarding alien enemies were both contradictory and controversial. Although the international factors related to the war influenced public opinion against the foreigner, domestic factors played a significant role as well. A growing recession in the years before the outbreak of war swelled the numbers of the unemployed who crossed the nation in search of work, congregated in cities and often protested for fair working and living conditions. Moreover, mass immigration after 1896 forever changed Canadian society and as a perceived threat to the British values and morals upon which the nation was built, aliens increasingly became the targets of advocates of social control. Anti-foreigner sentiment became an ideological undercurrent that permeated social, economic and political debates of the day and fed the fear, paranoia and xenophobia that made the misguided policy of internment a reality during the Great War.

The Canadian government implemented similar policies throughout the 20th century. Residential schools; restrictive immigration policies; the suppression of the labour movement in the interwar period; the internment of Japanese, Germans, and Italians during World War II; surveillance of ethnic communities throughout the Cold War; the FLQ Crisis; security certificates and the war against Islamic terrorism – continue to be the subject of debate. The entrance of 25,000 Syrians into Canada hopefully will not garner the same attention decades from now.

Frank Jankac is an independent public historian who has conducted extensive research into the issue of internment in Canada.