To Serve and Connect

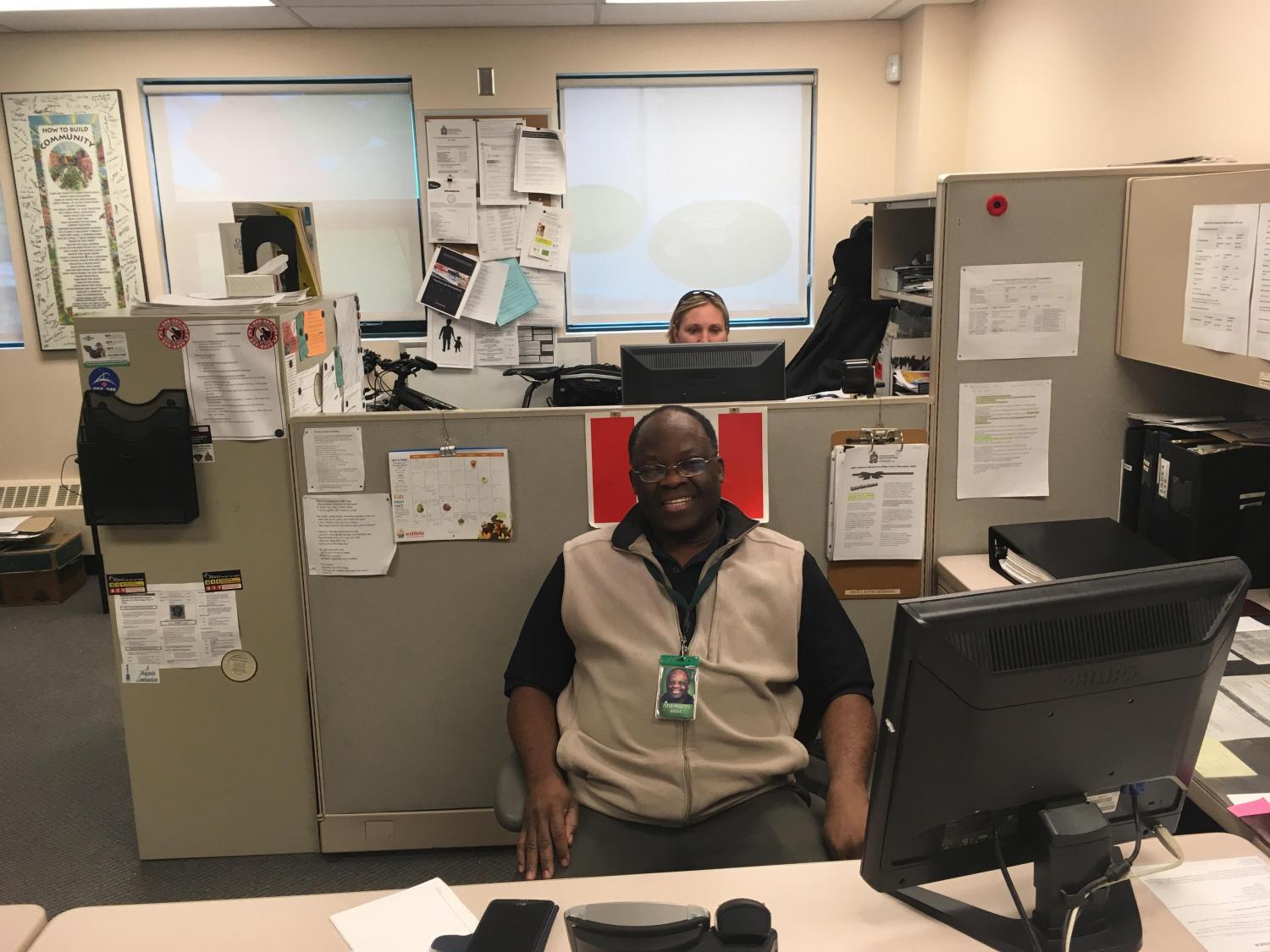

Story and photos by Noah Richardson / Feature image: Const. Dawn Neilly-Sylvestre, a community police officer with the Ottawa Police Service stands in her office at the Wellington Community Police Centre in Hintonburg.

When Wayne Rodney was a kid growing up in the Ottawa community of Hintonburg there was still a police officer walking the neighbourhood beat.

“At night, he’d walk into every yard, check every door, every window. All those things are long gone. They don’t do it anymore,” says Rodney, a retired public servant whose lived in Hitonburg for more than 40 years.

Rodney, a tireless crime prevention advocate and community volunteer, describes what many might envision when thinking of community policing: an officer of the law that residents get to know and come to trust when it comes to their personal safety as well as the protection of their property.

Ottawa’s police force has long been committed to community policing through its 15 community police centres scattered across several neighbourhoods, including Hintonburg. Staffed by volunteers and community police officers, the centres serve as the primary location for crime prevention initiatives and outreach. Community police officers make regular appearances at neighbourhood meetings and events and are the main point-of-contact for those requiring police services. But a massive overhaul underway at Ottawa police has Rodney worrying he and other community leaders across the city will soon be seeing less of their trusted community police officers.

The Ottawa Police Service is currently undergoing one of the largest transitions in its recent history. A major part of the sweeping changes is a reduction in the number of community police officers, down to 10 from 15. The remaining officers are now responsible for much larger geographical areas, and the community policing program has moved to a newly created unit called Community Safety Services. The force also recently merged three separate departments (patrol, neighbourhood officers and emergency support), which includes 800 sworn officers serving on the front lines, under one big platoon.

The restructuring at Ottawa police is deeply concerning for Rodney, who co-chairs the security committee for Hintonburg’s community association. He’s experienced first-hand the vital role community police officers play in helping to foster a positive relationship between citizens and the police.

“I don’t think we’ve ever had a complaint about this police centre. Everybody loves the idea of [having it] here. I think it’s something that every community should have,” he says.

Jeff Leiper, the city councillor for Ottawa’s Kitchissippi Ward agrees. He remembers the role a community police officer played in helping to resolve problems with street prostitution and crack houses in Hintonburg back in the late 1990s.

“The fact that we had a community police officer—and we have had some great community police officers—who had the neighbourhood knowledge, and the history of the issue, and who had the mandate to address something on a day-to-day basis rather than just react, to be proactive about crime, was hugely helpful,” he says.

With the crack houses and sex workers on the streets now long gone, both Rodney and Leiper say they have reaped the benefits of having one designated officer working in their neighbourhood.

While Rodney says he fears he won’t have the same kind of access to his community police officer that he’s been accustomed to for years, the man heading the new unit says residents should notice little to no disruptions to the community policing program.

“Right now, we’re delivering a transition service which is status quo,” says Insp. Sterling

Hartley, who now oversees the officers involved in community outreach, including school resource officers, mental health constables and community police officers.

Despite the elimination of five community police officer positions, Hartley, a 36-year veteran with the Ottawa police, says the program still has 14 dedicated officers, including three community sergeants and one staff sergeant.

According to Hartley, the Ottawa police is unique among municipal police forces in Ontario because it serves urban, suburban and rural areas. He says increased financial pressure is what led to the changes.

Hartley says Ottawa police are listening to neighbourhood groups, having made it a priority to consult with key stakeholders through each step of the overhaul. A community advisory group is continuing to work with the force throughout the transition period.

“My biggest challenge is getting meaningful input from the community,” he says. “That kind of process is going to be built on trust, and it takes time to build that trust.”

Hartley added that moving forward, senior management wants all patrol officers to “get out of their cars and do more community interface.”

One policing expert says Ottawa’s police service, much like those in other municipalities, was operating in ways that were no longer efficient or economically sound.

“I know policing costs have soared in the last you know, 30 years, 40 years. They’ve outstripped increases in almost every area of public service,” says Ronald Melcher, an associate professor of criminology at the University of Ottawa. “That level of increasing cost is simply unsustainable.”

According to the Ottawa Police Service’s 2017 draft operating budget, 81 per cent of the force’s overall budget is dedicated to staffing costs. The budget says personnel continues to be the police service’s most significant cost. The changes being implemented are meant to help the force trim costs. While police officials wouldn’t comment on how much the force will save under the changes, it has invested over $1.2 million into the restructuring, which it calls the Service Initiative.

Melcher says the direction in which Ottawa police is moving is not about cutting money for community policing programs, but rather “reducing resources applied to types and styles of policing activities that aren’t related to public safety in any meaningful way.”

Leiper agrees. While he initially worried community police centres and community police officers would be eliminated entirely, he says the new model is realistic given the costly nature of policing.

“There is an ideal world in which there is a cop on every corner,” he says.

“Today, so much of what police are being asked to deal with is the fallout from the abandonment of mental health issues and other health issues by the province,” he adds. “As long police are doubling as social workers, the idea of having a strong police presence proactively cruising around looking for trouble is probably unrealistic.”

Across town in the east-end community of Vanier, Lucie Marleau doesn’t share Leiper’s viewpoint.

As the volunteer co-ordinator for Vanier’s neighbourhood watch program, Marleau has come to rely heavily on her community police officer. She says the officer has assisted with conflict resolution, addressed derelict properties and helped to educate the public on when to call for police services.

“He’s been extremely open and receptive to the concerns of the residents. He’s definitely a really good model for what we expect from our community police officers,” she says.

Like Rodney, Marleau is concerned that her community police officer now has too much ground to cover. A member of the Ottawa police’s community advisory group, she says losing the former neighbourhood officers to regular patrol functions is troubling.

“This new model, it does not feel proactive. It feels more reactive. It feels like some of the resources that were allocated to neighbourhoods have been reduced or removed in order to support more reactive policing,” she says.

Back in Hintonburg, Rodney isn’t convinced the police are listening to the anxieties held by neighbourhood groups.

“They seem to think they know it all,” he says.

After losing his neighbourhood officers and with less access to his community police officer than ever before, Rodney feels defeated by the process.

He maintains the police “bullied their way into communities,” and forced them to accept the changes.

“I’m glad that we don’t have as many patrol cars going up and down the streets. That doesn’t bother me at all,” he says.

“But, when they’re needed, I want them there, plain and simple.”