Tracing Grandfather’s Footsteps through Berlin and Leiden

By Ping Yan

My grandfather’s Berlin

While the much advertised attractions in Berlin are turning into tourist traps, I was attracted to the less advertised, vibrant Prenzlauer Berg neighbourhood, mainly composed of apartment blocks. Streets were laid out in the 19th century and buildings were built in Wilhelminism style during 1889-1905. They almost entirely survived the heavy bombings by the end of World War II. During the era of the East Germany (GDR), it was a working class district where workers and the families lived in short distances to factories. Following a large exodus of residents in the 1970s and 1980s, the GDR government planned to demolish the entire area, paving way to a new "socialist model city" with prefabricated housing structures. Luckily this master plan never fell through by the time of reunification. The government of the reunified Germany attempted to find the original homeowners. It became daunting and impossible due to missing documentation along with the owners. Squatters, bohemian artists, grassroots social activists and socially disadvantaged groups started to move in, followed by aspiring young urban professionals. Today, Prezanlauer Berg has a growing young demography, a stark contrast of the ageing population of the rest of Germany. It is emerging as a thriving, fashionable and avant-garde new attraction.

Prenzlauer Berg is the site of the largest synagogue in Germany and a large Jewish cemetery. Before World War II, there were approximately 18,000 Jewish residents living here but only 48 of them remained by 1945. Walking through the streets with such a rich history and looking at these hundred year old apartment buildings, I started to imagine thousands of the deceased homeowners. My mind started to drift to another era with my grandfather’s tale and a Jewish family.

It was about 90 years ago, in the era of the Weimar Republic when Germany was a democratic republic filled with optimism and hope. To its east, Poland had just regained its independence less than 10 years prior, after 123 years of partition by Russia, Prussia and Austria. Further east, the civil war in the newly created Soviet Union had subsided and the Great Terror under Joseph Staline had not yet begun. Overall, it was a short lived nostalgic era.

My grandfather, Puqing Yan (also known as Yen Fu-ch’ing ), was just over 20 years old at that time and was on his way to the Netherlands by train to study. During his brief stop in Moscow, he paid his tribute to the body of Vladimir Lenin. A Soviet official tried to persuade him to abandon the journey to the west and choose between the University of Moscow and the University of Leningrad instead. My grandfather declined the offers.

Now he was on the next leg of his journey: Moscow – Warsaw – Berlin. He shared his sleeper coach with a Polish passenger, who seemed to be very friendly and talkative. The Pole offered a long, slim cigarette with a slightly strange aftertaste. He woke up from a deep sleep and the train had passed Warsaw on the way to Berlin. The Pole had gotten off the train. My grandfather suddenly realized that the bulging pocket of his jacket was now flat. Gone were the gold coins of the value of 300 American Dollars! These were the initial funds prepared for settling down after arrival in Holland.

Left penniless and helpless, he desperately paced back and forth in the long corridor of the carriage. An elderly gentleman came out from the adjacent cabin in his pajamas and asked: "Why are you not sleeping this late at night?" After learning about the story, he then said: "Don’t worry, I live in Berlin and my wife will come to meet us at the station. Stay with us and we shall figure out the rest.”

Left penniless and helpless, he desperately paced back and forth in the long corridor of the carriage. An elderly gentleman came out from the adjacent cabin in his pajamas and asked: "Why are you not sleeping this late at night?" After learning about the story, he then said: "Don’t worry, I live in Berlin and my wife will come to meet us at the station. Stay with us and we shall figure out the rest.”

The elderly gentleman was a Jewish merchant. In the following days in Berlin, the Jewish couple took my grandfather to the Chinese consulate of that time and was rudely received. There was no sign of sympathy nor was there any willingness to help. The Jewish man was appalled and so angry that he yelled, cursed and made a scene on the spot which did not help. The next day, the Jewish couple bought him a ticket from Berlin to Amsterdam and saw him off at the train station. While boarding, they put a full 300 American Dollars into his pocket, equivalent to nearly $ 5,000 today. This was undoubtedly a huge sum of money.

In the next few years, my grandfather maintained letter correspondences with the Jewish couple looking forward to the day their kindness would be repaid. One day, he received a letter from them saying that Berlin was no longer a good place to live and they were planning to migrate to Jerusalem. They left a forwarding address. When my grandfather had saved enough money, he immediately wired $300 by cable to the forwarding address. At that time, communication had become difficult. There was no response to his letters or acknowledgement of whether the money had been received. He never knew what had happened to the family.

Wandering around Prenzlauer Berg 90 years later, I imagined my grandfather had also walked on the same streets and perhaps the Jewish couple might have lived in this borough. It led me to wonder if they descendants and where they might be today.

Leiden Stories as heard on the streets

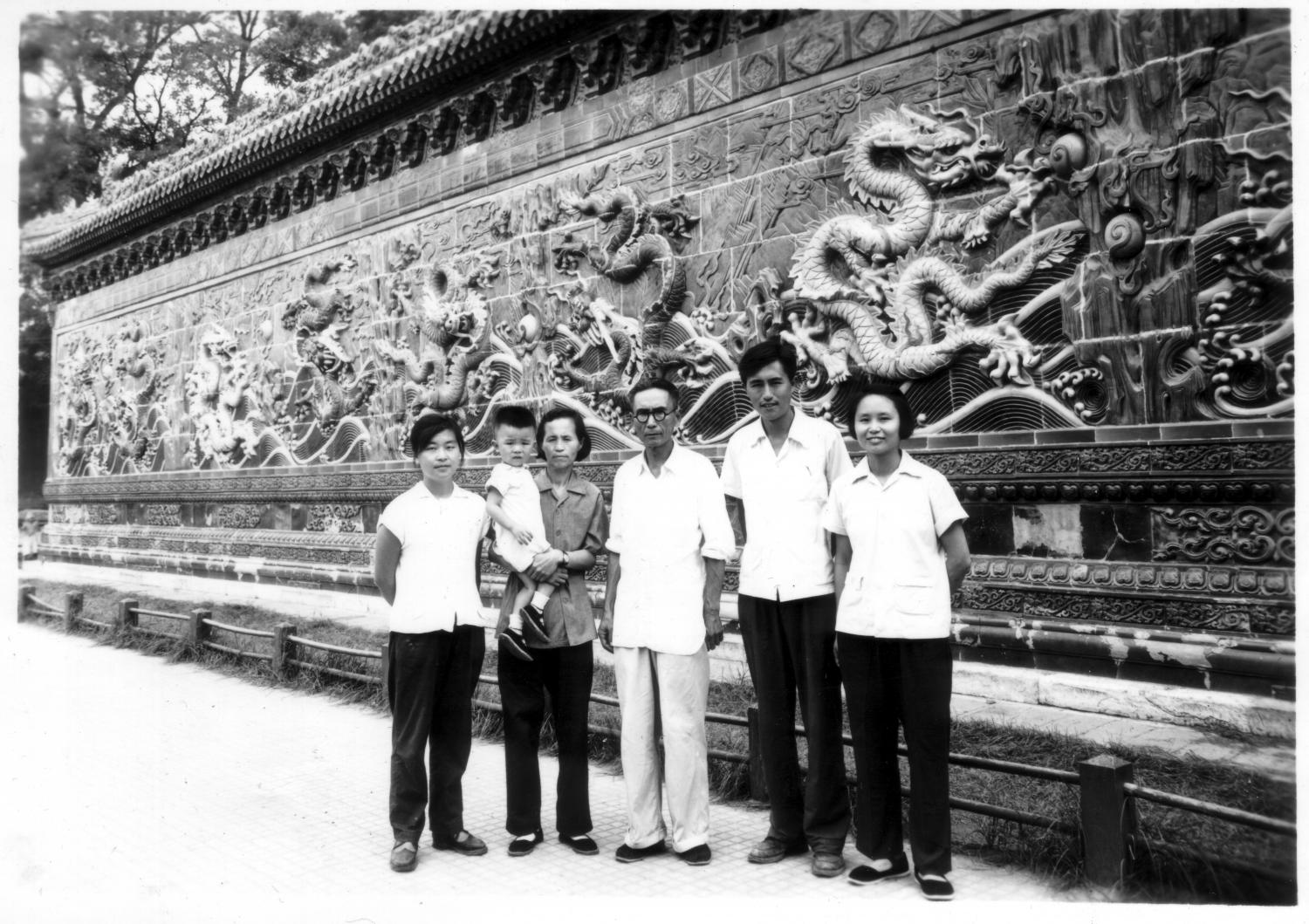

I was born in Beijing in 1958, known as the year of the Great Leap Forward in China. After giving birth, my mother returned to the northwestern China near the Gobi Desert to be with my father, who was punished during the infamous Anti-Rightist Movement . My grandmother took me home from the hospital and I grew up under the care of grandparents. I still remember my childhood days before the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) when my grandfather would often pick me up in his arms to point at a black and white photograph in green frame hanging over his bed. In the picture, there was a canal, a bridge and a clock tower. My grandfather would say: “Look at that, Universiteit Leiden!”. From then on, whenever I heard people talking about the "foreign lands" or the “western world”, what came to my mind was always that canal, that bridge and that clock tower.

Throughout my childhood and adolescence, information from outside was prohibited. From the day I could walk up until my high school years, my grandfather insisted on taking me along in a daily ritual: “after supper, walk a mile rain or shine”. Among the countless other stories while strolling along the streets, he recounted his experiences. These "hearsay" became my windows for perceiving the outside world. I could “see” his Trans-Siberian train to Moscow followed by his journey to Amsterdam via Berlin and his Venice-Shanghai Express ocean liner that took him through the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, the Suez Canal, the Indian Ocean, the Strait of Malacca and eventually entering the South China Sea along with the interesting stories he experienced along the way. However, what remains deep in my mind was his description of the city of Leiden in the 1920s and 30s.

My grandfather traveled to Leiden to study in the mid-1920s and by the time of his return to China in 1935, he held the title of Lecturer at Leiden University. In that era, he was among the luckiest of the Chinese youths who travelled abroad. These good fortunes were largely attributed to the kindness of those who helped him during those crucial moments as did the Jewish couple from Berlin.

My grandfather had a childhood friend bearing the same name “Fu-ch’ing” with the slightly different family name Yang instead of Yan. They grew up in the same rural village in Laoting County, Heibei Province. Yang was about 10 years older than Yan. Mr. Yang Fu-ch’ing studied in Japan and returned to China in 1919 as a very successful industrialist and philanthropist. He started to sponsor young talents to attend the Changli Huiwen Academy (a school established by American Methodist missionaries) with potential studies abroad thereafter. My grandfather’s study in Huiwen Academy and subsequent study in Europe were largely indebted to the sponsorship of Mr. Yang. Many years later, during the 8 year Japanese occupation of Beijing, Mr. Yang once again offered help. Consequently, among the countless stories I learned while strolling the streets, Mr. Yang was a name my grandfather often mentioned with passion.

Another frequently and passionately mentioned name was “My landlord, Duyvendak the Dean” (J.J.L. Duyvendak). He was among the first group of diplomats posted at the Dutch embassy to the new Republic of China in Beijing from 1912 to 1918. During this period, Mr. Duyvendak befriended some American missionary teachers at Huiwen Academy. Upon returning to the Netherlands, he started his academic career at Leiden University and subsequently founded the Sinological Institute. This was how my grandfather chose to study at Leiden University and to become a boarder at the Duyvendaks.

My grandfather’s initial intent was to study the fields of agricultural economy. Less dedicated to his own study, he was heavily engaged in the preparation of raw materials and index for The Book of Lord Shang: A Classic of the Chinese School of Law, translated from Chinese with Introduction and Notes by J.J.L.Duyvendak which was published in 1928 (Arthur Probsthain, London, UK) then reprinted in 1963 (Chicago Press), 1974 (San Francisco), 2003 and 2011 (The Law Bood Exchange, Ltd. New Jersey). This was one of the earliest achievements of Professor Duyvendak before he became one of the world’s most renowned sinologists in the 20th century. The Sinological Institute at Leiden University was formally established in 1930. My grandfather was given a teaching job in Duyvendak’s courses on Chinese ancient philosophy and school of law, which studied the work of classic Chinese thinkers such as Zhuangzi (also known as Chuang-Tze, ca.369 – ca.286 BC), Mozi (also known as Mo-Tse, ca. 468 – ca. 391 BC), Han Feizi (, ca. 475 – ca. 221 BC), Kung-Sun Yang (Lord Shang, ca. 390 – ca. 338 BC), among others. He taught in Leiden and lived with the Duyvendaks until 1935.

A Chinese proverb reads: “If you deliberately plant a flower, it might not bloom, but sometimes when you accidentally seed a willow, it ends up providing you with shade.” My grandfather often self-deprecatingly described himself as “a tradesman” or “retailer”. While in the West, he was “reselling” the knowledge about the classic Chinese schools during the Warring States Periods (770-220 BC) which he learned from his grandfather as a child. These turned out to be valuable at the Leiden Sinological Institute for aspiring young members of the upper class who hoped to govern the colonial territories under the "Dutch East India Company " where the Chinese culture had predominant influence. After his return to China, he was “reselling” English language and literature which he acquired during his sojourn in Europe in Chinese universities. Never in his life had he applied his studies in the field of agricultural economy.

My grandfather took the Venice-Shanghai Express ocean liner and returned to China in 1935. He had intended to help China to fight against the Japanese invasion. He found he was nothing more than a scholar with no expertise besides teaching. He travelled from Shanghai to the deep interior regions of China (northern Sichuan province and southern Shaanxi province) without finding employment. He finally settled down in Peking (the older name of Beijing). The Marco Polo Bridge Incident broke out on the 7th July 1937, marking the beginning of the full-scale Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945). The entire northern and eastern parts of China were occupied by the Japanese. The Japanese junta in Peking gave my grandfather two choices: either working for the junta or imprisonment. He like many intellectuals from Peking fled the city. Most were heading to China's remote and mountainous southwest where they established the National Southwestern Associated University (1937-1946) in Kunming City, Yunnan Provinces. My grandfather was not one of them. Instead, he chose to flee and hide in the countryside in the rural village where he grew up in which was also under the Japanese occupation.

It was much more difficult to hide in the rural countryside than it was in a large anonymous metropolis. So he sneaked back into Peking and took refuge in a machine factory owned by a large charity organization that provided social assistance for those in need. The Chairman of the Board was Mr. Yang Fu-ch’ing, the philanthropist who sponsored my grandfather’s studies in the 1920s. My grandfather lived in a collective dormitory and shared bunk beds with others for 8 years without employment. He became spiritual, was ordained in a Buddhist monastery to serve as a Lay Buddhist. He also became the apprentice of one of the best known Chinese traditional herbalist to learn traditional medicine. For the remainder of his aimless days, he gambled and smoked opium. The Japanese junta seemed to have ignored him as being a member of the “useless class”.

On a bright day in 1946, after the surrender of Japan, my grandfather took a leisure walk in the Jingshan Park in Central Peking and ran into an old friend he met in Paris in the 1930s. He was Professor Chi who had just arrived from Kunming to Peking and taken the post of Chairman of the Department of European Languages at the former Sino-French University in Peking (1920-1950). Mr. Chi said: “Report to me tomorrow morning and teach English in my department.” Overnight, my grandfather ended his 8 year unemployment, terminated opium use “effortlessly” and became a Professor! He never accepted the concept of addiction. He often said: "As long as there is a purpose in life, there is no addiction that is hard to quit."

In the decades that followed, my grandfather worked in several Chinese universities sometimes as a professor teaching English, sometimes as a doctor practicing Traditional Chinese Medicine in the university clinics and sometimes part time in both capacities. In my childhood memories, he was well known and respected by the neighbours as “Doctor Yan the herbalist” but very few people were aware of his past experience and career in the western world giving lectures on ancient China in Leiden.

These are some of the many stories I learned while strolling the streets during the daily ritual “after supper, walk a mile”. These are the stories that he could share with his grandson but unable to reveal to anyone else. From these stories, I could feel his deep regret. Since the day he arrived in Shanghai in 1935, he had been cut off from the rest of the world. The City of Leiden as it was in the 1930s was the image of the Western world frozen in his memory forever. Meanwhile, his stories about Leiden became the window into the outside world for me to peek through before China opened its door again in the 1980s.

Ninety years after my grandfather’s time, I had the opportunity to visit Leiden. I immediately recognized the familiar canal, the bridge and the clock tower built in 1575. I found the exact perspective of the black-and-white picture (from memory). I pulled out a modern Canon digital camera and “recovered” the same photograph that used to hang at the end of my grandfather’s bed.

I felt as if Grandfather was just standing beside me, pointing forward and saying: “Look at that, Universiteit Leiden!”

Ping Yan spent his first 28 years in China before starting his study at University of Waterloo in 1986. After obtaining his doctorate degree in 1992, he moved to Ottawa and has been working in the field of developing mathematical and statistical models for public health as a scientist in the federal government. In his spare time, he enjoys ballroom dancing with his wife. They compete at provincial and national dance sport competitions.