How My Wife Woke Up Left-Handed

By Jean-Pierre Allard

After suffering two strokes, my wife, Cathy, actually considers herself lucky.

As a young mother on maternity leave from her government agency job, Cathy was immersed in the joys of bonding with her baby girl. Naturally, we were anticipating a bright and exciting future for our precious family. Then, in an instant, it all came crashing down.

On January 28, 1984, she suffered her first stroke, just three months after our daughter was born. She was only twenty-seven. From getting married to buying a house to both receiving promotions to her giving birth… what an eventful, but stressful year it had been. And now our lives were about to get even more chaotic.

Looking back with the eyes of the huge music aficionado that I was, along with my wife’s interest in the metaphysical, I suppose we should have heeded David Bowie’s 1984 eerie lyrics and stayed home that cold and windy night instead of partaking in a little Trivial Pursuit game with friends:

The times they are a-telling, and the changing isn’t free

You’ve read it in the tea leaves, and the tracks are on TV

Beware the savage lure of 1984

The initial prognosis wasn’t good. The stroke affected her mobility on her right side and also the thalamus, the part of the brain that relays the body’s sensory and movement information to the cerebral cortex. Her entire right side was numb and burning, and her ability to balance and sense exactly where half her body parts (proprioception) was severely altered. As she lay in hospital that first week, awaiting the final diagnosis, she was gripped by fear, guilt and an expanding feeling of despair. How would she ever be able to properly care for her daughter? Would her disabilities prevent her from ever working again? Were failure and disappointment now to be her destiny?

I recall Cathy being devastated when I brought our baby girl to the hospital the first time, because she immediately realized she couldn’t even hold her. And to think that all my life, I’d been told that baseball is cruel. Call it a premonition of becoming “Mr. Mom,” or just sheer good fortune, but only three days before that fateful night, I’d asked my wife to show me how to prepare formula bottles as well as program the washer/dryer in the basement. (Yes, it was already the 80s, but not every male had jumped on the home duty-splitting bandwagon).

After three weeks at the Ottawa General, she was transferred to the stroke rehabilitation ward at St. Vincent Hospital, mainly a chronic care facility. The day Cathy arrived by ambulance, she had an anxiety attack, no doubt fueled by the sight of a joyfully loud, mentally-challenged paraplegic resident in the lobby. She was overwhelmed with the fear that she would never be allowed to leave. The words from The Eagles’ Hotel California rang so eerily clear in her fragile mind:

I had to find the passage back to the place I was before

“Relax” said the night man, “we are programmed to receive”

You can check out anytime you like, but you can never leave

However, she quickly realized that the wonderful staff at St-Vincent cared for her like she was family: anti-depressants allowed her to focus on the physiotherapy that she would need to regain strength in her right side, all the while hoping those darn pins and needles would go away. It became obvious very early on that she could no longer use her right hand for writing. Yikes. But she soon found a way to hone her “southpaw” skills, keeping a journal about her transformation over those short, yet interminable weeks. Her psychologist at the hospital then suggested she should write a book about her medical journey. I guess it helped a bit that she was a pianist – well, former pianist, now that her right hand had lost its fine motor skills. And there was another challenge. She was bluntly told she would require a left-foot gas pedal if she was to get her driver’s license back, because her right ankle and foot were not sufficiently responsive for road safety’s sake.

Along the way, she learned new ways of managing daily tasks to accommodate her “differently abled”, regaining many skills through neuroplasticity — the brain’s incredible ability to rewire itself. After a year’s convalescence, she was ready to resume her job as a marketing officer at Export Development Corporation (EDC) but was promptly informed that her position had been abolished. Would she mind accepting a secretarial job instead, asked the human resources officer? Imagine! I vividly recall that when she road-tested her new left-foot accelerator the next day, she inadvertently rammed the car into our garage door. I briefly wondered whether she was confusing the door for her callous employer. Much later in 2002, after learning that the same Crown Corporation had been named one of the top employers in Canada, my wife hoped that their experience with her in 1985 contributed, in some small way, to their becoming a more flexible, equal-opportunity employer that respects diversity in the workplace.

After stints in human resources at the Solicitor General’s office and as a writer-editor at the Department of the Secretary of State, she spread her wings to freelance so that she could be home to escort and pick up her daughter at the school bus stop. And that worked quite well for a spell. During that time, she also got a short humorous piece published in Dogs In Canada.

Then came a second crushing setback, on July 31, 1990. Just one day after Cathy had boldly taken it upon herself to trim our cedar hedges on one of the hottest days of the summer, our six-year-old daughter rushed upstairs to see her mommy after her swimming lesson. She found herself semi-conscious on the office floor, the phone hanging off its hook, after apparently having dialled 811 in confusion.

Another stroke. Another life interrupted.

This one was downright brutal, and from the onset, it was feared she had lost her oral skills, not to mention being confined to a wheelchair. Her right foot was paralyzed from the ankle down and became twisted, making it very painful to walk, even with the custom-made leg brace she was initially told she’d wear for the rest of her life. I recall she was so discouraged at first, totally unable to envisage another eight-week rehabilitation stint at St. Vincent. But there was just no quit in my soulmate as she did her best to get used to wearing a leg brace, despite every painful step along yet another new path.

Having lost my dad when I was 11, my brother by suicide when I was 23, and my mom two years after my wife’s first stroke, thus becoming an orphan at 33, I was slowly boiling over by that time, desperately waiting for those darn guardian angels to show up as promised. I can only surmise I must have been a crappy altar boy. Or maybe it was because I repeatedly lied in the confessional booth.

But once back home, Cathy was most grateful to focus on taking care of her family, as she was convinced this was it, and she would never be able to work again. I once again got off easy, being slapped with some more house duties. No sweat, Jeepster. By then, I’d become quite proficient at whipping up some succulent eats and, besides, I’d given up chasing that elusive hole in one (though patience is a virtue and seven rewarding aces and counting awaited me once I reached the sage age of retirement). What a blessing that we found inspiration in our brave daughter, who remained strong and resourceful – the glue that held us together. Our daughter had become our little guiding light.

As if my poor wife needed more aggravation, she eventually gained some weight from her forced inactivity. But she passed her driver’s test again, this time even joking with the instructor that if she wanted to really speed up, all she had to do was press on both left and right foot gas pedals. She also began attending a soft aqua-fitness class twice a week, significantly helping pave the way to recovery, and made some dear forever friends, which allowed her to enjoy much-needed social outings after the sessions.

Another significant step forward occurred when her new family doctor, Blackburn’s Louise Linney, diagnosed her borderline high blood pressure and high cholesterol levels and quickly prescribed the right medications. (still shaking my little head as to how this was not treated by her previous family physician after her first setback). And the late Graham Curryer, her chiropodist at the Rehabilitation Centre, recommended she look into a new procedure called Botox (botulism) injections to relax the highly spastic muscle tone in her damaged foot. Cathy always chuckles that the ageing well-to-do now use this same method to remove facial wrinkles.

After the first set of injections, her foot flattened considerably, and the pain was greatly reduced, making it easier for her to begin working a four-day week at the Department of Justice, starting in November 1997, with a term of employment as Editor of the newsletter Inter Pares. The position had opened after Clive Doucet took a leave of absence to run for Ottawa city councillor in the Glebe riding and won. All her colleagues were so kind to her, not to mention the ergonomics team with their very accommodating solutions. Whenever there was a fire drill, her “buddies” strapped her into an “Evac-U-Trac,” an ingenious conveyor-belt machine that enables the occupant to be brought down stairs to the next level, although they often joked that it would be so much simpler to just lower her down the window with old bed sheets tied in a knot (a useful tip from a fireman friend). During those twelve years at Justice Canada, two of her highlights were interviewing Minister Erwin Cotler and sitting on the Deputy Minister’s Advisory Committee For Persons With Disabilities.

But the best news of all came early in 2002 when, after the effects of Botox started to diminish, as they do for wrinkled people, she was referred to Dr. Jacques Brunet, a brilliant orthopaedic surgeon. The two surgeries to reconstruct her foot were so successful that she no longer needed to wear her leg brace, allowing her to work another seven years at Justice.

Cathy has been happily retired for 16 years and is now a proud and blessed grandmother of the sweetest little three-year-old girl.

Just last year, she finally got her book published, entitled Becoming Comfortably Numb: A Memoir on Brain-Mending. (Mission possible, albeit 40 years later.) While her memoir recounts her medical history, she also aims to give practical advice and inspiration to all those living with disability or chronic health issues, including caregivers and support persons. To show her gratitude for the excellent care she received during those two eight-week stints at Bruyère Health, she is donating 10 percent of the book proceeds to them in their quest to improve stroke awareness.

Since her book launch in September 2024, she has had three book signings with a few more to come. On December 3, 2024, International Day For Persons With Disabilities, she was thrilled to see her book excerpt published in the Ottawa Citizen, while later receiving a congratulatory plaque from Ottawa Mayor Mark Sutcliffe and his council. Just last month, she was honoured to share a booth with officials from Bruyère Health at the Fifty-Five Plus Magazine exhibit.

In no time, my wonderful wife evolved from being a stroke victim to becoming an advocate for people with disabilities and chronic health issues. But never would she have imagined that she would now be collaborating as a spokesperson for Bruyère Health and the Heart and Stroke Foundation, as well as a speaker at the Vancouver International Publishing Conference on writing about trauma this coming June 8, 2025.

Her message is that every stroke is different, and the risks and symptoms of stroke can be different for women and men. She is particularly passionate about empowering women to learn more about their increased and unique risks of stroke throughout their lives. She was utterly shocked to learn recently that 89 percent of women are not aware of these inherent risks, mainly due to the fact that the majority of stroke treatment research has historically been conducted by and on men. Consequently, women are more frequently misdiagnosed and their rehabilitation is also more complex. Consider that it took the doctors a full week to diagnose her stroke in 1984, even if they knew she was a post-partum patient, never mind that they assumed a 27-year-old coming in to emergency on a Saturday night at 11:30 p.m. had simply gone to the wrong party and just needed time to shake it off.

Hence, she urges everyone to learn the FAST (Face, Arms, Speech, Time) signs of stroke, and to call an ambulance as FAST as possible. Not only is time essential, but paramedics can start treatment immediately and will know which hospital is best to treat their particular symptoms. A complete recovery from an otherwise life-threatening stroke is now possible with immediate medical treatment. Based on her own experience, she is also suggesting to learn everything one can about what parts of the brain have been affected and what one will need to do in order to continue improving after discharge from the hospital.

In my wife’s case, she was extremely fortunate to have received the best possible treatment at the time. This support from family, friends, and various healthcare professionals continues to this day as rehabilitation NEVER stops due to the brain’s ability to find new pathways to do things differently.

I often need to intervene when I sense it’s time for Cathy to slow down, given her unencumbered enthusiasm to embrace living as actively as she can. For instance, she regularly walks, swims, stretches, meditates, and practices yoga; she has even taught herself how to kayak and snowshoe, and now she’s considering getting a foldable electric tricycle.

In a funny way, Cathy’s story can be easily envisioned as the modern-day Aesop’s fable, The Tortoise And The Hare. Why so? Because if truth be told, my wife is probably in better physical and mental shape than most other persons her own age, owing to her daily efforts to get her body and mind ready for another day of joy and gratitude to be alive. She certainly gets what Yogi Berra was reported to have said, “We’re lost, but we’re making good time”. Slow is good in her world.

There’s nary a day in the last 40 years that my brave and resilient wife has complained about the bad hand she’s been dealt, always maintaining she’s been pretty lucky. In a way, it’s a bit like the great Lou Gehrig addressing a packed Yankee Stadium crowd and saying he considers himself to be the luckiest man on the face of the earth, despite knowing full well that his fickle fate was to die a few weeks later.

Indeed, my best friend Cathy has been extremely lucky, thanks to Ottawa’s marvellous medical profession and the Canadian healthcare system. Still, the lion’s share of the credit must go to her. Cathy is now Becoming (more and more) Comfortably Numb with each passing day.

And most importantly, she still hasn’t learned how to write the word “QUIT,” even with her left hand

For more from Jean-Pierre Allard, check out his moving story, I Always Thought That I’d See My Brother Again

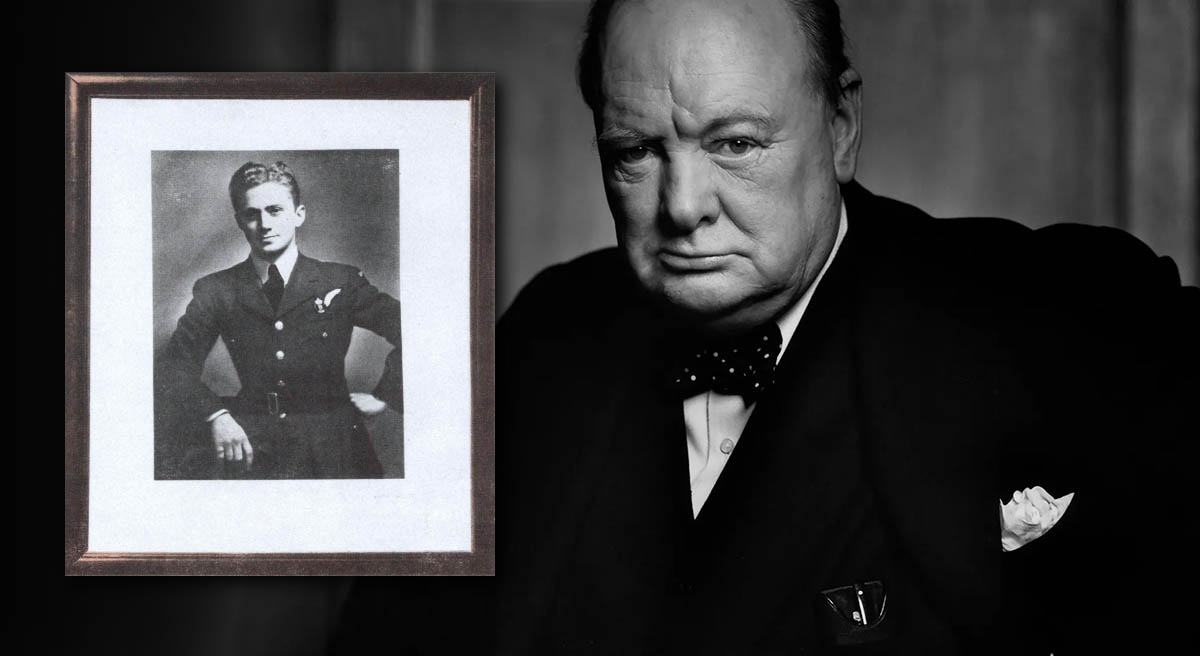

HEADER PHOTO: Cathy Allard, courtesy Jean-Pierre Allard