Is An Energy Corridor the New National Dream or an Ottawa Mirage?

Our Economic Future May Depend Upon the Answer.

“Nationalism was a strange new word. Patriotism was derivative, racial cleavage was deep, culture was regional, provincial animosities savage, and the idea of unity ephemeral”. The writer goes on to say, “There are few Canadians yet who care deeply about it; most provincial politicians indeed, are ‘either indifferent or hostile’” to the project.

A recent Globe and Mail editorial perhaps? Or excerpt from a new book on the state of Canadian democracy? Sorry, this analysis of the state of the nation was written 55 years ago by Pierre Berton in his seminal book, The National Dream: The Great Railway 1871-1881. The Conservative Prime Minister, Sir John A Macdonald had made a commitment to British Columba to build a railway to tidewater on the Pacific coast, notwithstanding the fact that the thousands of kilometres between the top of Lake Superior and the Rockies were part of Canada only by virtue of the previous decade’s purchase of the North West from the Hudson’s Bay Company. Indigenous First Nations inhabited the prairies and the Canadian Shield from Lake Nipissing to the Métis heartland of the Red River, which was largely unexplored by Europeans. Provincial interests in the east were largely opposed and the commercial side of the undertaking required huge financial considerations from the young nation just four years after Confederation.

We are now 150 years removed from that momentous decision – without which Canada would not exist today – yet the parallels with the current debate on the efficacy and indeed, necessity of a national energy corridor are striking. Plus la change, as the saying goes, plus c’est la meme chose.

The energy corridor concept essentially envisions a long and narrow swath of pre-approved right-of-way, within which energy infrastructure such as pipelines and power lines can be built. The concept is based upon the understanding that there is a national interest in the development of energy infrastructure that can best be achieved through collective action, rather than through a series of uncoordinated private sector initiatives. Such corridors can minimize land disturbances, environmental impacts – notwithstanding opponents such as former Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault – facilitate inspection and monitoring activities, simplify and potentially make more timely regulatory approval processes, while allowing for enhanced community engagement that would better integrate Indigenous and local knowledge. We may assume that a specific route would likely follow existing routes thus minimizing costs, environmental impacts and broader impacts on local communities.

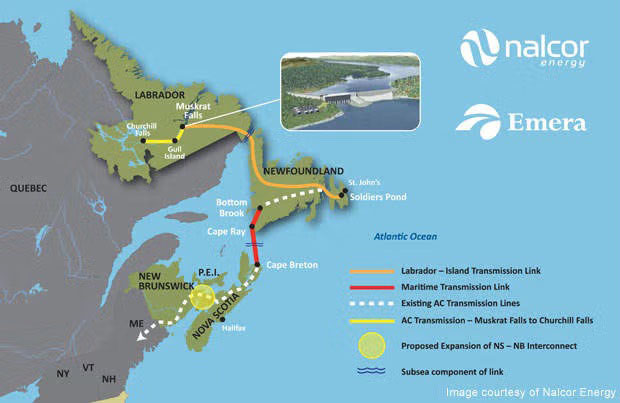

The concept is not new to Canadian public policy and politics. Nearly 70 years ago, Prime Minister John Diefenbaker championed the long-distance transmission of hydroelectricity from Canada’s North to the population centres in the south. He called for the development of major hydroelectric sites in Quebec, Manitoba and British Columbia while deferring the construction of coal-fired generation on the Prairies and in the Maritimes. Pre-dating nuclear construction in Ontario, Toronto was to be powered by Hydro-Québec. While the Chief’s national grid initiative never came to fruition, a Liberal government introduced the federal policy to strengthen regional transmission interconnections in 1974. The policy saw the federal government cover 50 percent of the cost of interconnection studies, and provide up to 50 percent of capital costs for approved projects. This policy was unilaterally discontinued as a cost-cutting measure in 1994. In recent years, the Government of Canada has re-inserted itself in this field with loan guarantees for the Lower Churchill project at Muskrat Falls in Labrador and the associated sub-sea transmission lines to the island of Newfoundland and then thence on to Nova Scotia (see Map 1). Rather than simply strengthening the national grid, the emphasis in this regard has been on environmental improvement with an eye on reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

ABOVE: Map 1

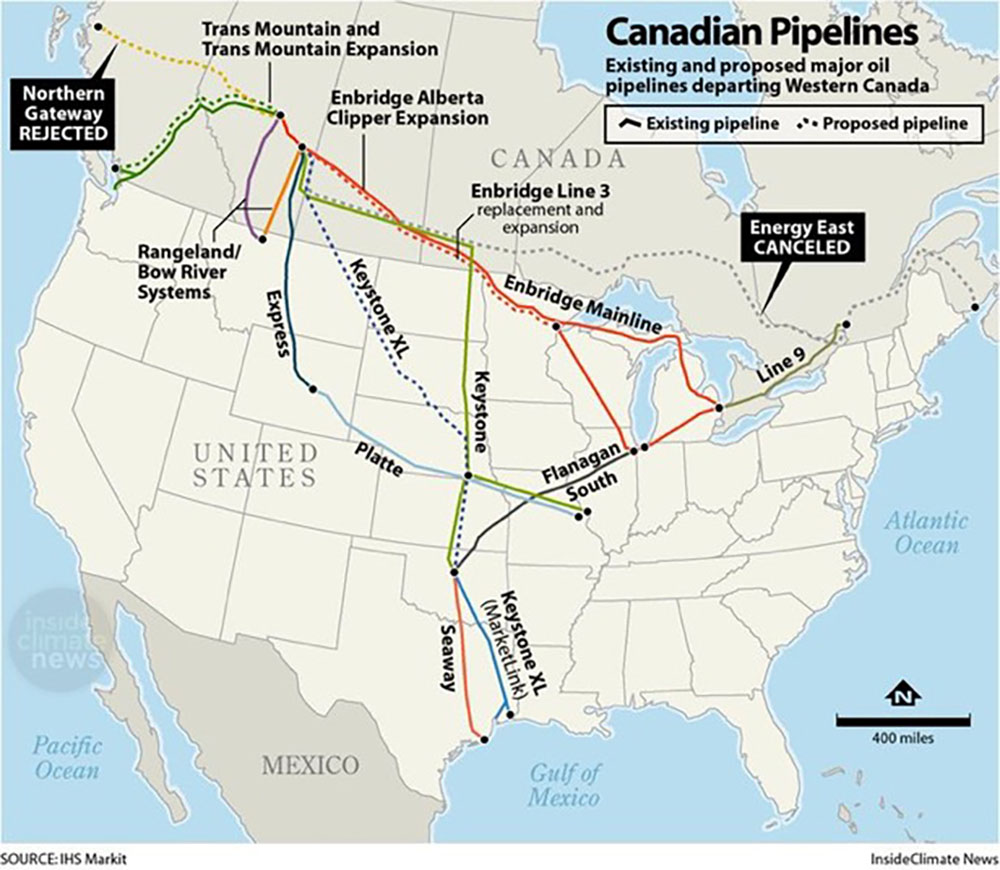

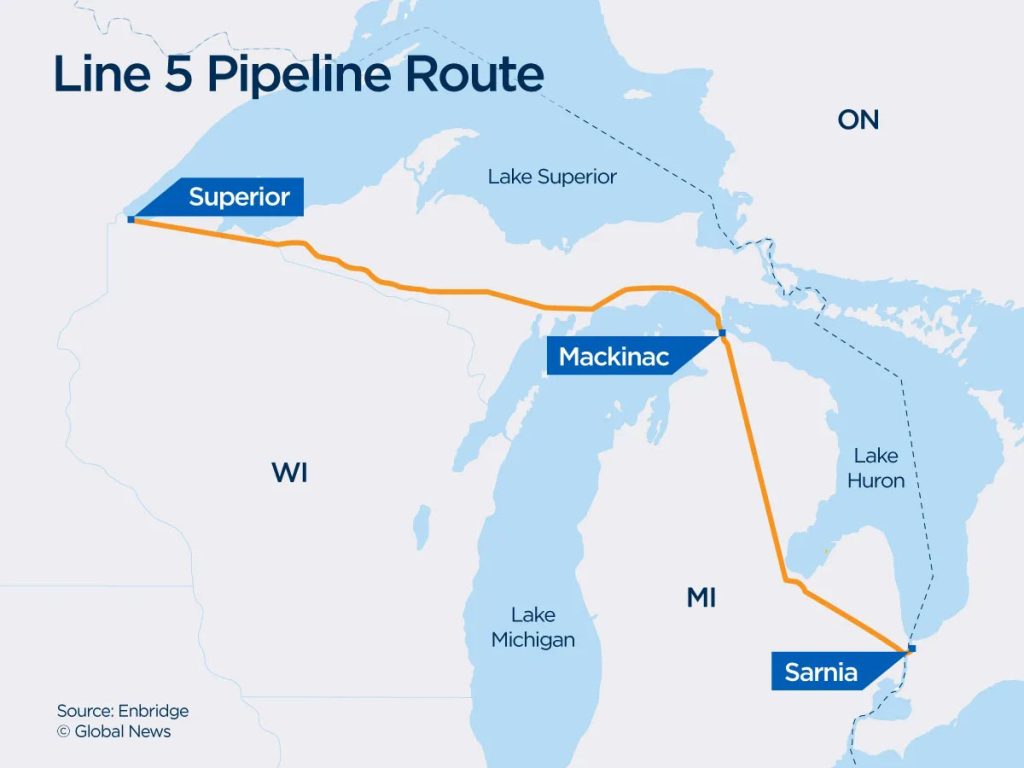

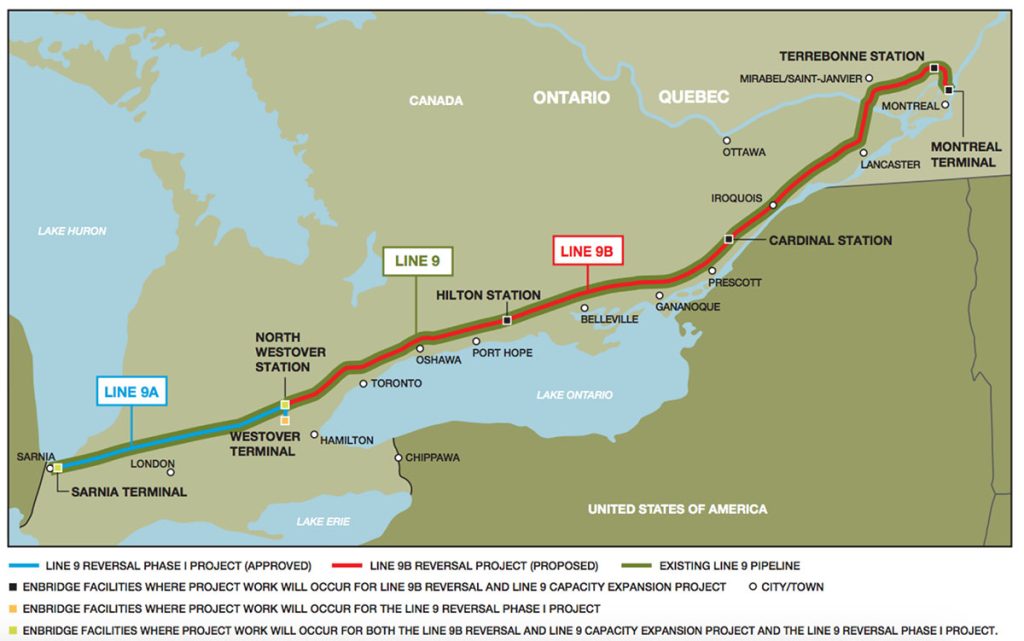

The post-war years also saw the development and construction of a spiderweb of oil and gas pipelines from Alberta and Saskatchewan to Ontario and Quebec and various points in the United States. Incredibly, the first 1,600 kms of the Enbridge Mainline was built in 150 days in 1950. Its terminus is at the Great Lake’s seaport of Superior, Wisconsin (see Map 2). Line 5 to Sarnia was built in the mid-50s with a major expansion and upgrade in the 1990s. Due to geography, oil supplies to refineries and the petrochemical industry of Central Canada is dependent upon a pipeline that passes through Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan. In the 1970s, Line 9 was built linking Sarnia to its Montreal terminus. Over the years, the line alternately sent oil east to west and vice versa. It currently flows entirely west to east (see Map 3).

ABOVE: Map 2

So, we have a continual oil pipeline system from the Port of Vancouver to southern Manitoba where the Enbridge Mainline enters Minnesota, and then from Sarnia to Montreal. Our natural gas pipeline system runs from the Pacific Ocean with a new LNG terminal in Kitimat soon to open to Quebec City. New Brunswick and Nova Scotia are linked to New England and Quebec via a circuitous route to Quebec City (again transiting the United States). And while the electricity grid can be said to be national in that lines are connected across provincial boundaries, major chokepoints exist, between: in the Maritimes; Ontario and Quebec; Manitoba and Ontario; and Manitoba westward – you get the picture.

ABOVE: Map 3

Add on the threat posed by the Trump administration to Canadian oil transiting the US, to the need for new transportation links for critical minerals development, and the necessity to streamline current federal environmental assessment legislation, particularly Bill C-69 known colloquially as the ‘No New Pipelines Bill’, Prime Minister Mark Carney’s campaign commitment to make Canada an energy superpower globally seeking increase conventional energy production (read oil and natural gas) while simultaneously catalyzing the transition to renewable sources by reducing red tape and project approval timeframes, makes obvious sense. But can he do it?

Early signs were mixed. Former Environment Minister Guilbeault, the bête noire of the oil patch, emerged from the first Cabinet meeting to say that the need for new pipelines was receding, incorrectly citing international demand forecasts and current pipeline utilization. He was obviously slapped down internally as he hasn’t commented further on this issue. Carney himself has adopted the language of ‘social acceptability’ of new projects; Quebec political parlance for obstruction. And essentially said, ‘pipelines if necessary but not necessarily pipelines’ when asked if these projects would be prioritized by his government.

He did however, appoint former Goldman Sachs investment banker, Hydro One and oil sands company Meg Energy board member Tim Hodgson as Minister of Natural Resources, and while this weeks Speech from the Throne does not specifically reference the oil and gas sector, the government recognizes that, “Given the pace of change and the scale of opportunities, speed is of the essence. Through the creation of a new Major Federal Project Office (MFPO), the time needed to approve a project will be reduced from five years to two….” The government will also seek to strike ‘one project, one review’ agreements with the provinces.

Neither commitment is earth-shaking. The Harper government introduced the Major Projects Management Office (MPMO) in the 2007 Budget. More than $300 million in bureaucratic expenditures later, the MPMO appears to have done little more than publish an annual inventory of major natural resource projects across the country, and it would appear that the office has been folded into the Canadian Energy Regulator. In 2024, the Clean Growth Office was established within the Privy Council Office, with a mandate to support government-wide coordination and culture change to advance major clean growth projects. Its objectives are faster decision-making, clearer regulatory signals and rigorous assessments, among others. It promised high-level – ADM and above – interdepartmental coordination, and sought to set a five-year Impact Assessment timeframe for permitting. Carney seeks to cut this further to two years! It will be interesting to see whether this office is folded into the new MFPO, and time will tell whether federal urgency in this regard is sustained. And the federal government already has the ability to strike ‘one project, one review’ agreements; other than on one occasion with British Columbia, the Trudeau government just never bothered to.

Urgency and the political will to use this climate of crisis and national awakening will be crucial to the success of the Carney plan. In a speech last week in Calgary entitled, Canada Strong: Building the Future of Energy, Minister Hodgson reemphasized his Prairie roots, his experience at Goldman Sachs in capitalizing pipeline projects, and in the electricity sector with Hydro One. He spoke of the need to identify – and quickly do so – Projects of National Interest, “projects that matter to “our economy, our environment and our sovereignty”. Projects in the field of oil and gas referencing the vulnerability of Eastern Canada, hydrogen, nuclear, biofuels and electricity. Development, processing and refining of critical minerals is high on the priority list, as is the forestry sector and its vital link to housing construction. For the first time in a decade, a Liberal minister thanked energy workers for their contributions to Canada. Riffing off Pierre Poilievre’s Boots not Suits slogan, Hodgson said, “This government isn’t just about people in suits in Toronto or Ottawa. It’s about people in hard hats …. That work powers our country, and it earns our respect.” Wow, one can almost feel a cloud lifting across the country.

The ‘rubber hits the road’, hard work begins at the First Minister’s Conference next week in Saskatoon. Doug Ford favours a national electricity transmission grid and pipelines that utilize Ontario steel. Scott Moe and Danielle Smith are obviously onside; despite her bizarre dalliance with Alberta separatists. Manitoba’s Wab Kinew recently announced a strategic economic and energy corridor to link Manitoba with Nunavut, couched entirely in terms of sovereignty and security. Atlantic Canadian premiers are largely supportive of energy corridor discussions, and Quebec’s Francois Legault, who, in spite of his continual references to the need for social acceptability for projects, is more open to the idea than any of his predecessors in the past two decades. BC’s David Eby is a weathervane, and potential wet noodle but he also wants grid expansion, and with an economy increasingly reliant on the natural gas sector, should be open to proposals.

The original National Dream? We all know how that ended: a railroad coast to coast, an expanding country solidified; and US Manifest Destiny denied. It doesn’t diminish this accomplishment to acknowledge all was not well – the treatment of Indigenous People, and outright theft of their lands, and the exploitation of Chinese workers. But the fact remains that Canada would not exist in its current form if not for the railroad and Sir John A’s vision.

Largely lost to history is the fact that it was a Quebecer, Sir George-Étienne Cartier, who convinced the British Columbia delegation to Ottawa in the summer of 1870 to move off their initial request for a wagon road from the Rockies to the Pacific. Cartier told them, “No, that will not do. Ask for a railway the whole way and you will get it.”

Can Mark Carney channel Cartier? For the sake of Canada, let’s hope so. The hopes, and stakes for the economic future of Canada have rarely been higher.

Photos: Flag image, iStock; Marc Carney, www.bloomberg.org; George Etienne Cartier, www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca.