Ottawa’s Historic Houses and the Stories They Tell

Ottawa’s stately beauty and charming neighbourhoods make it easy to forget that ours was originally a lumber town and not a federal capital. Today’s scenic waterways, including the Rideau Canal, were once lined with mills and manufacturing concerns serviced by smoky trains. It was only a few decades ago that log booms floated behind Parliament Hill, and the air conveyed the unmistakable stench of pulp and paper.

The scrubbing began with Laurier’s vision for ‘a Washington of the North’ and culminated with The General Report on the Plan for the National Capital (1946–1950), or Gréber Plan. While the rails, mills and an entire neighbourhood in Lebreton Flats are now gone, a city street can be read like a cultural map that preserves the original social identity of long-lost communities. Drive along Crichton Street in New Edinburgh, for example, and you’ll find unadorned brick rows that backed on to what was once a railway corridor. By contrast, only a few blocks away on Mackay Street across from Rideau Hall, you’ll find the elegant Georgian-style Lansdowne Terrace from when New Edinburgh was evolving from an industrial district to a fashionable suburb.

Ottawa is rich with material memory. This is the first in a series of essays about our city’s historic houses and the stories they tell.

ABOVE: This Crichton Street row is right out of the industrial heartland of England.

ABOVE: A railway corridor crossed Beechwood Avenue until the 1960s. Old streetcar tracks can also be seen in the pavement. The Crichton Street brick row is visible on the far right.

The history of permanent settlements in the Ottawa Valley differs from other regions of Ontario and Quebec. French exploration of traditional Indigenous trading routes beyond the St. Lawrence River began with the arrival of Étienne Brûlé (c. 1592 – c. 1633), who spent his early adult life among the Hurons, who instructed him in their language and culture. This knowledge prepared Brûlé to serve as a guide for Samuel de Champlain, who joined him after having sent him on exploratory journeys to the Great Lakes, Georgian Bay, and up the Humber River. Given that the Kitchi-Sibi (Ottawa River) was navigable only by canoe, the French regime did not establish fortified trading posts along its waters as it did elsewhere, nor did it seed great cities beyond the St. Lawrence.

Following the American Revolution and the flight of refugees north into the colony of Quebec, a mostly rural population of roughly 6,000 United Empire Loyalists settled between present-day Belleville and Cornwall. None made it as far north through the mosquito-infested bush to the Ottawa River, and no portage was worth the effort to overcome the bluffs that separated the Ottawa River from the Rideau, a waterway that was itself not navigable beyond what we today call the Hog’s Back. Colonel John By eventually changed that, but a monumental effort of men and Great Britain’s most advanced machines were required to do it.

John Strachan was a prominent official in the government of Upper Canada and the first Anglican Bishop of Toronto. He described the loghouse as only the first step in a process of ongoing development. The new world was, after all, about social and personal progress, so as the new society developed and personal fortunes increased, so too would the permanence and scale of the family home. The original structure would be built with a superior house in mind and might have been repurposed as a kitchen or an outbuilding once the owner “got a little forward in the world.” When time and funds permitted, a frame house covered with a double lining of boards was erected, presuming the existence of a lumber mill. True affluence, which was rare, produced a more costly brick option if it could be supported by an abundance of clay and consequent brickworks.

John Langton’s Early Days in Upper Canada conveys a similar sequence of dwellings but adds stone houses to the list from the perspective of 1833:

As to the house, I cannot say what it will be as I hear so many opinions and indeed have not yet finally settled its nature and dimensions. No two people give the same advice. Some say a shanty is good enough; others talk of log, frame, stone, and brick houses. Franklins, cooking and common stoves, and chimneys of different constructions, have each their advocates. I incline myself to the regular routine; a wigwam the first week; a shanty till the loghouse is up; and the frame, brick or stone house half a dozen years hence, when I have a good clearing and can see which will be the best situation.

In 1796 on the far eastern reaches of the Ottawa River, the intrepid N. H. Treadwell, a land surveyor of old New England stock, purchased one of only two manorial land grants of the French seigneurial system in what is now Ontario, the system being an institutional form of allotment established in New France in 1627 by Cardinal Richelieu. With 54 square miles in his possession, Treadwell and his Dutch-born wife Caroline Adriance settled into what was known as Seigneurie de la Pointe-à l’Orignal (meaning “Moose Point.” Bogs are everywhere). Timber was found in abundance, as was good soil and water power in the higher terrain where Treadwell encouraged others from New York State to settle. An eventual francophone migration from the north shore of the river began occupying the boggy land that the Treadwell colonists and their descendants had previously rejected. Incidentally, L’Orignal is home to the province’s oldest courthouse.

Local construction was booming for the Ulster masons from Ireland who sought relief from the economic depression gripping post-Napoleonic Europe. They first worked on infrastructure projects along the Ottawa River, such as locks and barracks, and for the lumber barons of nearby Hawkesbury, who desired fine homes. Upstream in Wrightville, the timber trade was harvesting the red pines and noble white pines of the Gatineau hills and the upper Ottawa Valley starting in 1806, years before those same Ulster masons moved west to build the locks and earliest stone buildings of the Rideau Valley.

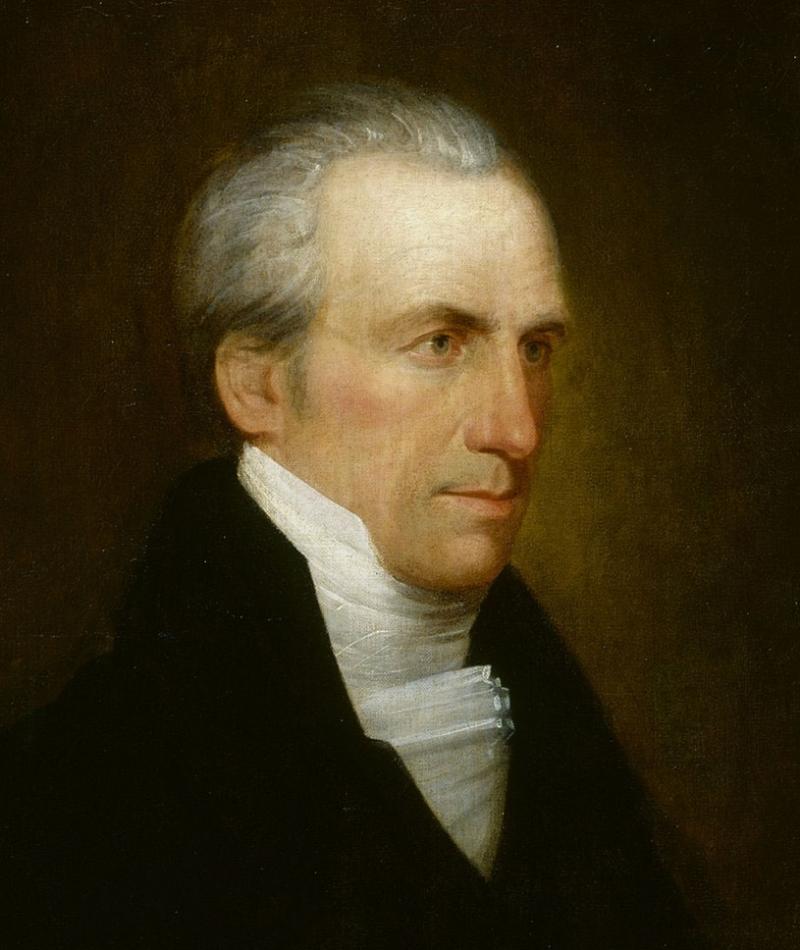

The first of the great lumber barons and home builders in the Ottawa Valley was Philemon Wright, an ambitious farmer, and merchant who first arrived from Massachusetts in 1796 to survey this region. Two more visits convinced Wright to sell his land in Woburn and lead four other families and 33 “labouring men” to establish a settlement in 1800 next to the Akikodjiwan/Chaudière Falls, near the meeting of the Tenàgàtino-sibi (Gatineau) and Kitchi-sibi (Ottawa/Outaouais) rivers. A land grant application from the Township of Hull and an oath of allegiance to the Crown made Wright the holder of thousands of acres of rich farmland. The Gateno Farm (1800) and the Columbia Falls Farm (named in 1801 for what Wright called the Chaudière) were the first to be cleared. Before long, a thriving settlement took hold, with enterprises established to support a local supply of goods to replace the expensive alternatives brought up against the current and around the rapids from Montreal. Industry and entrepreneurship began to thrive in what is today an epicentre of bureaucracy. By 1820, there were five mills, four retailers, three schools, two hotels, plus two distilleries and a brewery for whistle-wetting.

ABOVE: Philemon Wright, the great lumber baron and founder of Hull.

With affluence came respectable houses, but not before a sequence of steps up in scale and style. Wright constructed a humble cabin on the Gateno Farm in 1800, followed by a second, larger home with a stone foundation supplied by one of his many companies, a limestone quarry. In 1810, a third home was built on the sprawling 800 acres of the Columbia Falls Farm, where he lived until 1818, when he passed it on to his son Ruggles, along with the entirety of the Chaudière operations. The match magnate Ezra Butler (E.B.) Eddy eventually bought the property and demolished that version of the Wright home, which was replaced by two versions of a true industrialist’s mansion named “Standish Hall.” Version two came after version one went up in flames in 1900, the later becoming a hotel and a very popular music venue that featured the likes of Ella Fitzgerald, Tony Bennett, and their peers in the 1950s when Hull was the place to go, and Ottawa was even dozier than it is today. The Standish operated until the 1970s as a rock music club before it was torn down to make way for a hotel to the west of Les Terrasses de la Chaudière.

ABOVE: The Standish Hall. Stately manor, hotel, and music hall extraordinaire.

Philemon Wright’s last residential project was located just west of the Standish near the Chaudière Falls and was so grand he named it “The White House” after his farmstead home back in Massachusetts. All of his houses are gone today, but the estate of Braddish Billings, a longtime Wright employee, closely resembles Wright’s White House and today gives us a sense of the ambitions of these early builders of our region.

House building was picking up on the south shore of what was then called the Grand River due to Rideau Canal construction and the laying out of the street grid of Lower Town by Colonel John By. In our next installment, we’ll explore some of the earliest dwellings still standing on these early streets.

Photos: Courtesy Michael Bussiere