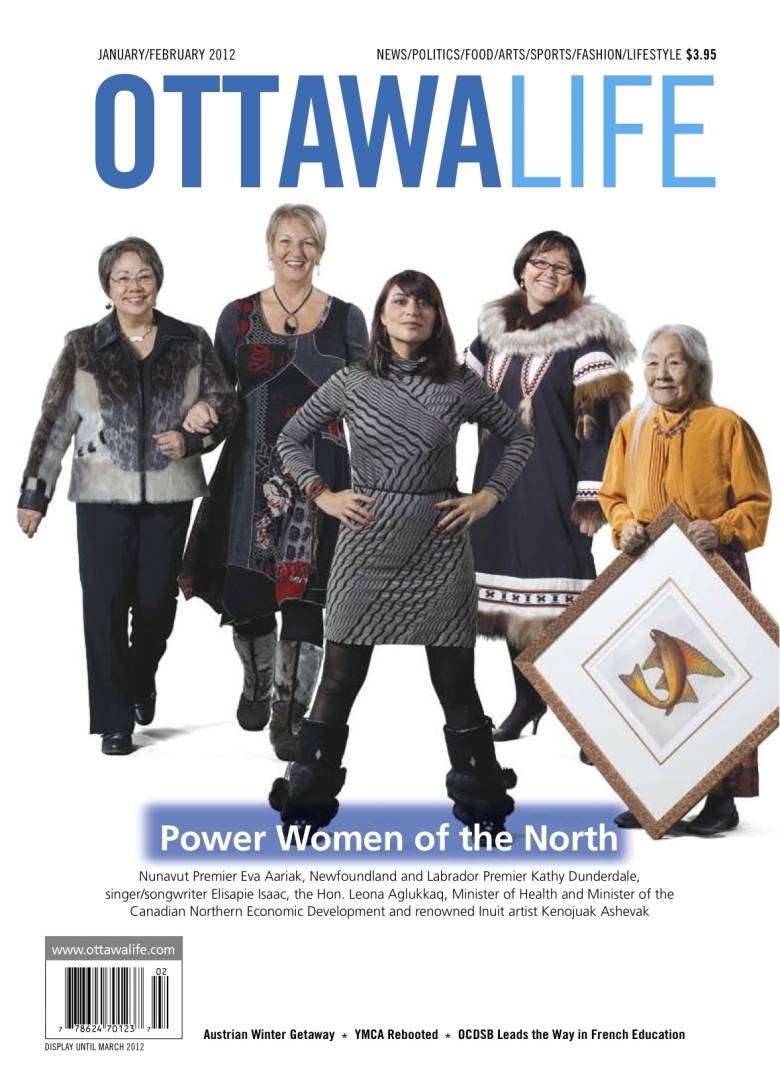

Climate Change and Arctic Sovereignty

ABOVE: Melting Arctic Sea ice.

Many of Canada’s most enduring myths originate in the Arctic. We still tend to think of the Arctic region as a vast unchanging space, as though frozen in time. The region is unrelentingly cold and the landscape consists of snow and ice, with very little vegetation. Although the environments are harsh and unforgiving, the Inuit and other Northern communities have lived according to its subtle rhythms. Their dependence on marine and wildlife for their survival has been the basis of a long and peaceful coexistence. Indeed the polar bear remains the Inuit’s most important cultural symbol.

Climate change is slowly but inexorably altering this perception of the Arctic. Although the region remains numbingly cold for much of the year, there have been subtle, but steady, increases in temperatures. As this occurs, snow and ice have melted. In the past few months alone, massive islands of ice broke off the Petermann Glacier off Greenland and the Ward Hunt Ice Shelf, respectively. The region’s refractory power is diminished as more snow and ice melt away, an underlying effect of which is to accelerate the warming process.

In time, thawing tundra will precipitate the release of methane in the atmosphere, a gas with higher concentrations of carbon than carbon dioxide. This could in turn contribute to more severe outcomes, such as the eventual disruption of ocean current circulation systems. These sorts of scenarios may seem far-fetched and invariably draw the ire of climate change skeptics. They will seem less so as warming and all of its associated consequences continue. In any case, the warming process has already generated more immediate outcomes.

To take one example, the hole in the ozone layer above the Arctic Circle has led to dangerously high ultraviolet (UV) radiation levels. Elevated UV radiation not only exposes people to higher risk of illness, as researchers have identified, it also compromises the photosynthesis process and the development of fish and amphibians.

It is within the context of climate change that the emerging debates over Arctic sovereignty (particularly with respect to marine areas) should be assessed. In addition to Canada, Russia, the U.S., Norway and Denmark all have legitimate claims over areas in the Arctic. The unfolding debates have been the source of a curious tension inherent in the Harper government’s responses to emerging Arctic-related issues.

On the one hand, Stephen Harper has asserted Canada’s sovereignty over Hans Island and the Northwest Passage. On the other hand, he is notoriously skeptical of the climate science that most effectively explains why the Arctic is suddenly subject to warming. Important questions flow from this tension. What will Stephen Harper’s claims to Arctic sovereignty actually entail? Do they simply amount to declaring Canada’s sovereign control over the Northwest Passage and our nation’s right to unfettered access to the vast energy resources lying under the Arctic Ocean seabed? Or do they entail a commitment to assuming a leadership role in protecting the increasingly fragile cultures and ecosystems that make up the Arctic region? More specifically, do they mean working productively with other Arctic nations via the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)? The answers to these and other such questions will define the Harper government’s Arctic legacy.

Protecting increasingly fragile ecosystems is fraught with enormous challenges. For amid the promises of ecological preservation are similar promises to tap the region’s energy and economic potential. Indeed the combination of climate change and powerful political and economic forces are leading inevitably to the more extensive extraction of the region’s vast reserves of natural resources. Oil, natural gas and gas hydrates are all in abundance. There are iron ore deposits in Mary River on Baffin Island. As ice melts and warmer seasons last longer, energy reserves are increasingly accessible. Moreover, technological advances render the resources more accessible still. Lastly, the relentless pace of urbanization in emerging powers such as China, India and Brazil will only fuel demand for oil and natural gas for decades to come. Small wonder then, that as the temperature warms and the snow and ice melt, littoral countries especially are rushing to stake their claim on their part of the Arctic region.

How then should Canada advance its sovereignty claims? Thus far, the focus has been on Hans Island and the more substantive issue of Canada’s rightful claim to the Northwest Passage. The Harper government is right to stake Canada’s claims to both, but should not do so at the expense of pursuing a multilateral approach to preserving the region’s ecological integrity. There is reason for concern, given the Harper government’s suspicion of climate change science. Its ambivalence towards the UN should also make us pause.

For better or for worse, UNCLOS remains the most appropriate forum for reconciling the competing claims among littoral countries as well as dealing with the extraordinary tensions between the region’s ecological preservation and its looming economic development. It will require the sort of sensitivity to the issues that Stephen Harper has yet to demonstrate. If he hopes to change this impression, acknowledging that global warming is the source of accelerated changes to the Arctic would be a good place to start.