Abdulrazak Gurnah’s latest novel explores the nature of freedom in post independent Tanzania

Tanzania, a country on Africa’s east coast, has a long and complicated history shaped by colonialism. It was first colonized by Portugal in the 16th century, when the country’s name was Tanganyika. In 1885 Germany took over; so began a period in Tanganyika’s history marked by simmering anger, eventual revolt and severe repression. After the Great War, and as part of the Treaty of Versailles, Tanganyika was made a protectorate of England, which it remained until 1961, when it gained independence. To further complicate matters, in 1964 Zanzibar – the island archipelago separated from mainland Tanzania by the Zanzibar Channel — underwent a violent revolution that led to the overthrow of the Sultanate but also to the massacre of tens of thousands of Arabs. Zanzibar’s revolutionary government was thus short-lived. By April 1964 the government relinquished power and the two countries — Tanganyika and Zanzibar — merged to form Tanzania. Dar es Salaam, although not the capital, is the country’s biggest city. It’s located on the country’s east coast. Like other big, coastal cities, Dar es Salaam is a place to which the ambitious gravitate. It also acts as a critical point of connection to the wider world; a place where different cultures converge. It has been for centuries. But the conditions under which such convergence happens have changed in ways both dramatic and subtle. Portugal, Germany and England, like their European counterparts, are no longer in the business of empire building. Tanzania is no longer a colony or a protectorate, its people no longer considered inferior servants to some distant crown.

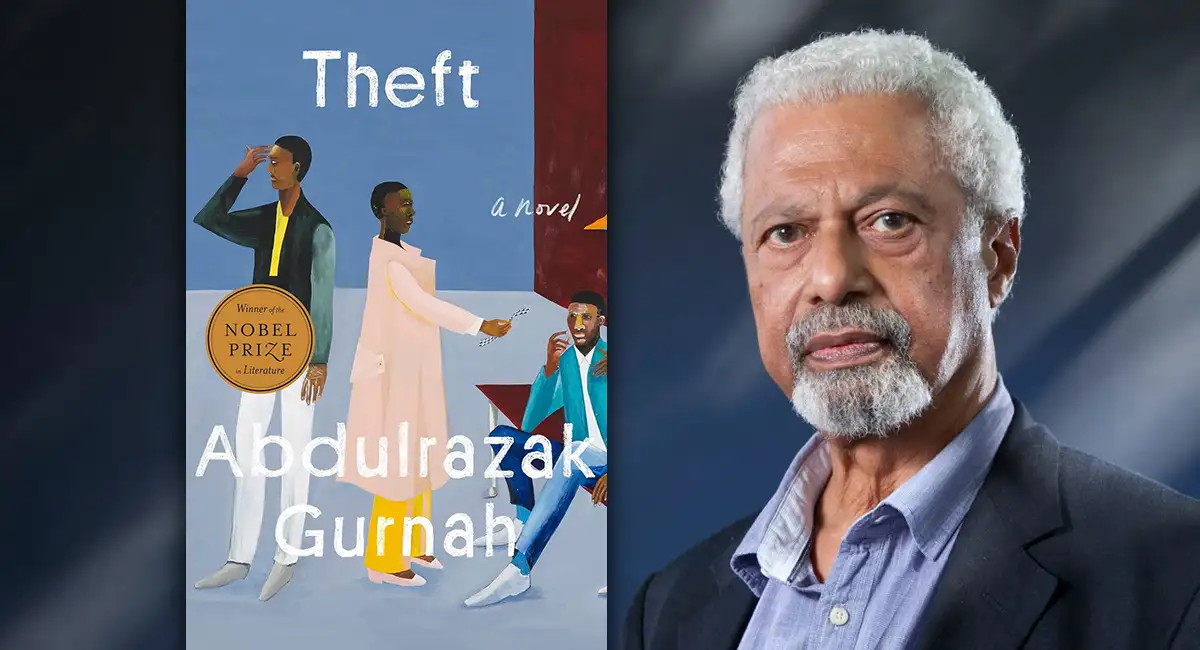

Post independent Tanzania is where the 2021 Nobel Prize winning author Abdulrazak Gurnah locates and begins Theft, his latest novel written in his wonderfully understated style. Yet the country’s name is rarely, if ever, spoken; nor are exact dates ever mentioned. Instead mostly oblique references to both place and time are scattered throughout as Gurnah traces the lives of the cast of characters who populate the novel. Still the country and critical points in its evolution form the backdrop to the story, like a sky in a landscape painting. Or to choose another metaphor. The country is like air: invisible but fundamental to the lives Gurnah depicts.

Theft opens with news of a marriage. Rayka marries at a young age after her father witnesses a young revolutionary spending too much time around her. He doesn’t like or trust the young man. He has a history of violence and for courting young women only to abandon them later. So Rayka’s father arranges a marriage between her and an older man, a contractor with a decent reputation about town. He’s divorced and, we learn later, has a boy from that previous marriage. Rayka agrees more in a spirit of submission than enthusiasm. Love or deep affection for her new husband never entered the realm of her feelings. From the moment they’re married, he expects his young wife to submit to his carnal urges, no matter how frequent or how aggressive.

Initially Rayka does submit, even as she starts to loathe her husband. They have a child, but his birth does nothing to strengthen their union or to inspire a deeper affection. On the contrary, the experience merely heightens her resolve to leave him. Rayka goes to visit her parents with no intention of returning to a man she despises. Her resolve remains unshaken even in the face of her husband’s many threats and her father’s insistence that she honour her duty as a wife. Rayka, the reader discovers in the novel’s early stages, is strong and buttressed by a streak of independence. Her quiet defiance seems to embody a broader social change.

Thus in Theft’s opening pages Gurnah lays bare some of the competing forces his characters will have to negotiate over the course of their lives. On the one hand, the young revolutionary’s early, fleeting presence highlights the importance of the political. Instability and turmoil are the backdrops to the story Gurnah is telling; one of the gifts of colonialism that keeps on giving, even after the various European powers have left and the country’s independence secured. Radical change is in the air but so too is the threat of violence and the abuse of power. Over time the exact nature of both the instability and the turmoil alters slightly but crucially. In one scene, a young man laments to his mother about the recent election violence and how it leaves him uncertain about their country’s future. Security forces are still abusing those who protest. To make matters more challenging, hyper inflation means the little money he and others earn is almost worthless. He refers to foreign countries having taken advantage of Tanzania, but also laments the country’s government’s incompetence and corruption. His disgruntlement reflects a more modern malaise: the apparent absence of alternatives to a crisis prone system that fails so many and that is secured by violence or the threat of it.

On the other hand, custom and religious orthodoxy act as heavy counterweights to the winds of change and upheaval. The Islamic faith anchors people and the communities of which they are a part. There is a timeless quality to the repeated references to the morning call to prayer. During Ramadan fasting is not simply an individual act of self deprivation and spiritual renewal, although it is those as well. The daily act is also the prelude to the evening’s meal and family and neighbours enjoying each other’s company. Adults talk and kids might play outside. Not that Gurnah’s depiction of Islam is entirely rosy or one dimensional. He is attuned to the dangers of dogma, particularly where women are concerned. For it is women whose to duty to obey is most assiduously observed, first to their parents and, later, to their husbands. It’s God’s will, the following of which will secure His blessings and rewards. This is what women are told and tend to believe until those like Rayka begin to question and reassess. Why should I give myself to someone I don’t love or who has so little regard for me? Why should I not be allowed to pursue the life I want? Notions of duty and fate must compete inside the heads and hearts of characters with ideas of personal freedom.

Gurnah’s aim in Theft is to establish a constellation of characters and then allow for their lives to unfold and for the connections among them to be uncovered. Towards this end, the lives he beautifully depicts are not unusual. Karim, for example, is smart, studious and ambitious. Ali, Karim’s older half brother, is less academically inclined and feels more at home at sea, especially as a teenager and young man. He assumes the role of proud and protective older brother. There is the friendship between Fauzi and Hawa, first as young school girls and as they grow older and struggle to find their place in the world. Fauzi is quiet and excels at school. Friends encourage her to become a medical doctor; she has the intelligence and the temperament to succeed in the country’s most highly esteemed profession. Hawa is more boisterous and chatty. Academic learning strikes her as tedious and unworthy of her deepest attentions. What reason does she have to know algebra? How will dissecting a frog in biology class ever do her any good? Her desire is to travel. Although the girls are opposite in these respects, the friendship thrives. Soon enough they are almost inseparable. On a school break, they take a ferry from Zanzibar to the mainland and then to Dar es Salaam. The sight of so many tall buildings and grinding traffic is initially overwhelming to the senses. While visiting, they’re exposed to more of the world, even if it’s only through magazines and television. America becomes a short-lived source of fascination: the apparent luxury in which so many live and the sometimes staggering degree of self regard. The reader can easily relate to such characters and experiences.

The character Badar is the exception to this rule. His circumstance offends our modern sensibilities. We meet Badar as a young boy not long after he’s been removed from school and is being taken to a family’s home, where he will become a servant. Servants do not require or even deserve an education and so he will be denied one moving forward. To this point in his young life, he had been living with another family, but not his biological one. There was a mother and father and at least a few brothers and a sister. He knows from an early age that they are not his real parents or siblings, although not because anyone told him. His understanding is due to the way in which he’s treated, which includes utter indifference, casual contempt and physical and emotional abuse. He’s a burden that this family has for some mysterious reason assumed. His adoptive mother tells him that he must get used to such ill treatment: everyone has their burdens that he or she must learn to bear.

The family Badar must now serve is one of means. His forced introduction to a world of relative privilege stirs an understandable longing. Gurnah writes,

The Mistress stood silently beside Badar, and he

wondered if she guessed how much he relished

the ease and luxury of the room…

Nevertheless Badar must quickly learn to quell any hope of being able to partake in the opulent world in which he’s been so unceremoniously dropped. Survival depends on he understanding what impulses to allay and which to cultivate. Indeed, as the reader quickly gathers, Badar is intelligent and quietly resourceful. He learns to navigate the circumscribed spaces in which he’s forced to live his life. He’s competent and respectful, quiet but observant. And so the couple for whom he serves quickly learn to appreciate his presence. He’s a servant but, in time, almost but never quite one of the family. Badar is seemingly okay with his subordinate status; he’s resigned to his fate, so long as it does not impinge too forcefully on his own sense of self dignity. Besides, the Mistress is never too demanding and rarely, if ever, speaks condescendingly to him. When she looks out the kitchen or bedroom window and sees him resting and talking to the family’s gardener she is content to let them have their peace and quiet, their opportunity to talk and get to know one another.

Like in any of his novels, Gurnah deploys revelation to propel the narrative. Family secrets that are sources of shame, bitterness and rivalry cast long shadows. In the hands of a master like Gurnah, the reader knows all will be revealed in due time. Yet Theft is as much about how chance encounters can alter a life’s trajectory. A young man and a young woman notice each other in passing. They are in each other’s vicinity just long enough for the laws of mutual attraction to kick in and romance to eventually flourish. A wife tells her husband about one of Badar’s standard visits to their home. Passing along that seemingly innocuous bit of information prompts the husband to visit Badar at the hotel where he works, something he rarely does. There, he finds Badar speaking to a young English woman in Tanzania to do some volunteer work. The visit to the hotel was unlikely; even more unlikely was that Badar would be sitting with a young woman at precisely the time he arrives. But that’s all it can sometimes take: worlds collide in that chance encounter, with consequences that will alter the direction of the lives of these characters.

Indeed the young English woman arrives late in the novel but is central to its denouement. In addition to being young and beautiful, she is intelligent and, quietly but crucially, bold. She fits into a mold that should be familiar to readers of Gurnah’s fiction. The English no longer colonize much of the world; the formerly colonized now have their independence. In this sense the world is more equal than ever before. Yet, inequalities— political, economic, and in ways more intangible —persist. So often the English can walk through the world — presumptuously, almost imperiously — in a way that is more difficult to imagine for a citizen of a formerly colonized country. This young woman arrives in this former colony and protectorate as part of a wider initiative to help restore the country’s natural environment. Her time in Tanzania is an adventure as much as a volunteer exercise; an opportunity to escape the humdrum of life back in England. She does things like sit in a hotel staff person’s office chair while waiting for him to return. She expects there to be late night snacks for her even though the hotel restaurant is closed. She visits a local couple’s home, only to speak to them with subtle condescension. Among Gurnah’s many gifts as a writer is his ability to depict such understated but insidious modes of interaction, as well as their corrosive power.

Speaking of the hotel, it is an ideal setting for much of the action in Gurnah’s story. It’s a place where the outside world connects with the local. People from across the planet come and go. It’s a place of secret rendezvous and illicit affairs. It’s therefore a place demanding discretion on the part of employees. For these and other reasons, Badar becomes a valued employee at the hotel. It’s really no surprise: his quiet competence and learned discretion make him so. The manager and assistant manager understand they can trust him. He knows how to engage with guests, how to make them feel welcome. He happily advises them on where to get a good meal and how to stay safe as they wander the streets of Dar es Salaam. He knows what not to do, such as be alone with a guest in her room with the door closed. This is important: women guests are starting to notice this quiet, handsome and capable young man in their midst. Some make advances. Naturally he’s torn: what to do when a woman from half a world away invites you into her room and asks you to close the door as she lies half naked on the bed? Must duty always carry the day?

These are among the sort of thorny questions with which Badar must eventually contend. For, as hinted, his circumstance changes over the course of the novel. With help from others, he achieves a measure of freedom, which is why he able to find employment at a hotel. He will no longer be consigned to the shadows, no longer forced to constantly live at the mercy and whim of others. Ahhh but a life lived in subservience, with no scope for formal learning or ambition, has left Badar tentative, self doubting, just as expectations of him begin to run high. People close to him soon feel free to judge, often harshly and with more than a hint of bitterness. And what to do about a hitherto unreciprocated affection? Will it always remain so? Badar has no idea. He is so uncertain in the ways of love.

Title: Theft

Author: Abdulrazak Gurnah

Publisher: Riverview Books

ISBN 13: 978-0593852606