A good woman, a good doctor, six good friends, and MAiD

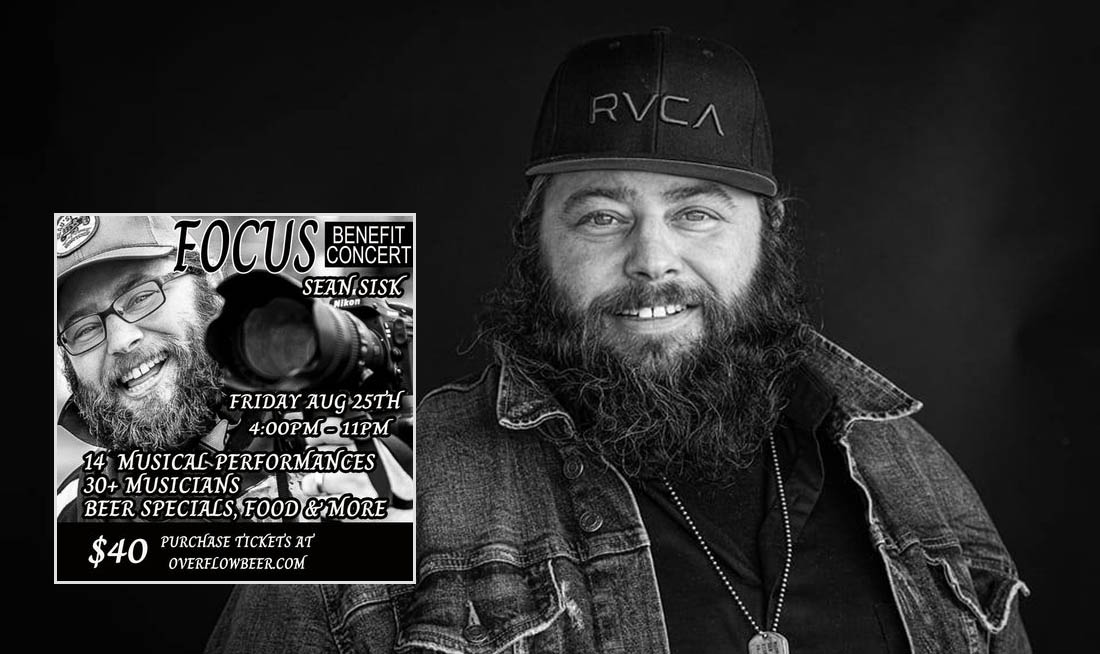

ABOVE: Alma Norman passed away on November 6, 2020

By David B. Brooks

MAiD is the short form of a medical procedure that has recently become legal under Canadian federal law: Medical Assistance in Dying. It provides for situations in which people are in significant pain or are in some other situation as described in the law, and no longer wish to continue with their lives. Except in extraordinary conditions, it requires the ascent of the person who wishes to die and who is mentally aware and fully cognizant of the nature of death.

This article describes my experience as one of the close friends of a woman who, for reasons described below, asked for MAiD. Her name is Alma Noman, and that is the only name, other than my own, that will be cited in this article. My wife and I have known Alma for almost as long as we have lived in Canada—we immigrated from the United States in 1970 during the Vietnam war—and we are confident in saying that Alma would be delighted if she could know—maybe she does know—that I am writing this article with her as the star.

Before telling you about Alma, I must apologize to Alma’s daughter and to the five other friends with whom I shared this experience. They all provided enormous support to Alma, and no doubt could have supplemented the information that I have, but I wanted this to tell about my reactions, my sadness, my astonishment.

Alma was born in New York City in 1929 to a woman who was the main breadwinner in the family. As a result, Alma spent much of early life in foster homes. However, she was a bright student and, thanks to scholarships, got a university degree from the University of Vermont. Then, with the goal of getting an MA in history, she enrolled at McGill, in Montréal, where she met Wiley Norman, a young medical student from Jamaica. Once he got his degree, they married and moved to Jamaica.

Alma was always self-directed with a tendency to throw herself into whatever attracted her interest. While a young wife in Jamaica she wrote the first history of Jamaica that was not written from a colonial perspective; it was quickly incorporated into the high school curriculum and remained there for nearly 20 years. Somewhat later, Wiley decided to switch from being a GP to a psychiatrist, and they returned to McGill for his second doctorate, and then they moved to Ottawa, where he established his practice. Not much later, we met Alma operating a small store on Sparks Street—one of the last sections that still had auto traffic—selling artisanal crafts prepared by women. Later I taught her to canoe, which she loved, and then combined canoeing with craftwork by building a canoe out of papier maché. It was not a very successful venture. Yes, it did float, and Alma got her picture in the local paper paddling in the canal, but it was terribly heavy and every scratch let in a bit of water that got inside the coating and made it heavier. In a way, the canoe modelled how Alma tended to operate; she would get right down to work; planning and alternatives could be left until later.

Was Alma Jewish? Yes, she was, but it takes another story to explain why she had so little knowledge of Judaism. Alma was in her '30s, married and living in Jamaica when she received a telephone message that her mother was dying from cancer. She got there in time to say good-bye, but her mother died shortly after, and, as the only child, Alma was left with the task of going through her mother's papers. To her great surprise, she found then that, despite her Anglo-Saxon surname, she was Jewish on both her mother’s and father’s side. Unhappily, she had no experience of living in Jewish household; happily, a few years later she was living in Ottawa where we met and helped steer her toward a program of learning. After about a dozen years of on-again off-again study and practice, she was one of three women who received an adult bat mitzvah at Temple Israel.

With her general outgoing personality and her love of being wherever the action is, Alma involved herself in many political activities involving women, such as the raging grannies. All went well until the last couple of years. I think that her last big outdoors trip was in the bow of a double kayak (David was of course in the stern) exploring the fjords and ice bergs of Greenland. But all this time she was getting older and losing her eyesight. About two years ago, Wiley, who had retired, developed a form of diabetes that affected his legs. After a while, Alma, who was small in structure, could no longer care for him, and he went to the Bruyere Centre, where he remained until he died in his upper '90s last year.

Alma was never really happy after that, and as she got beyond her 97th birthday, she began to talk about finding ways to end her life. Fortunately, at about the same time, she found a doctor with whom she connected and who was familiar with MAiD. A new chapter opened in Alma’s life. (Please note that MAiD remains controversial for Jews, and is pretty much rejected by Orthodox Judaism, as well as by some other religious groups, but that is a subject for another day.) The most common approach uses injections that result in death and was well known to veterinarians. To the best of my knowledge, it was first shown for use on humans in the 2003 film Barbarian Invasions.

Let me start with some facts about Alma’s day with MAiD. She invited six close friends to be with her on her "departure"—four Jewish, one Aboriginal, and a neighbour who was also a photographer. Aware of COVID restrictions, the afternoon was planned so that even when the nurse and the doctor joined us, and of course Alma, we only made a group of nine. The living room had been emptied of some furniture so we could sit at least a metre apart from one another. Alma sat in a large easy chair with a equally large footstool. There was hand sanitizer, paper towel, and Kleenex on every surface. I was the only male. There was no question of the fact that Alma wanted to leave this life, which is why she called it her departure, and why she told many people about her plans, including some who tried to dissuade her.

As to the day's program, one woman who had considerable experience introducing feminist principles into Jewish services, which still have many elements of their patriarchal heritage, organized the non-medical portions of the afternoon. We started with two hours just talking or singing, and listening to Alma go through a biography of her life and her relationship to each of us, which was certainly emotional and on occasion tearful for one or another of us, but it was also fun. A lot of pictures were taken, and some of what Alma said was recorded.

Then the doctor and the nurse arrived, and we got down to the business of the afternoon. I have to admit that, from this point onward, almost everything became as interesting as it was emotional. The doctor explained every step of how she would proceed, and together with the nurse took Alma into another room for a final private conversation. (I have no idea what may be required by legal or medical directives. The nurse did help the doctor at as she requested it, but his main job seemed to be documenting the process. He typically had a clipboard in hand and was filling in a form.) The doctor, nurse, and Alma returned to the living room and the doctor asked if anyone had any questions. I certainly did, and I suspect others of the six friends did too, but none of us could express them, so the doctor just said that she felt everything was ready.

At that point I had expected that the doctor and nurse would escort Alma to her bedroom a floor above the living room, but that was not at all what happened. To my amazement—indeed, to my shock—the whole process went on in the living room with all six of us with Alma at every step. Emotion and interest swirled around in my head with first one and then the other predominating. The technology was a series of injections over about 10 minutes, and between each one the doctor asked Alma if she wanted to continue. That question was the occasion for one bit of humour when, after the doctor asked a second time, Alma snapped back with (I think I am quoting accurately) “Of course I want to continue; didn’t I just tell you!” The Aboriginal woman was drumming lightly, but no photographs were taken. The first injection was just to relax Alma and she remained part of the conversation. However, as subsequent injections were given, Alma became quiet and lost consciousness, her complexion became pale, and she looked as if she had fallen asleep with her mouth open. The doctor then brought out a stethoscope and listed for (I presume) any heartbeat, looked up and told us that Alma had died/had departed this life.

We sat around, looking at Alma’s corpse holding our tear-soaked handkerchiefs, but there was nothing more any of us could or should do. However, the doctor was still busy. It was necessary to report to the office of the coroner, and also to alert the funeral home to send a hearse. In my case, I had to send a message to the president of our synagogue so that our congregation could learn about Alma’s death—and to do so before the arrival of the Sabbath.

As we got up to leave, each of us received a booklet of Alma's writing, mostly poetry but also some pictures of her craftwork, that had been prepared by one of those who were with us on the afternoon. And we also received some snacks that we were strongly advised to munch before we went outside on our ways home.

For your information, Alma died in mid-afternoon on November 6, 2020 (19 Cheshvan 5781 in the Hebrew calendar). The funeral will be private with just family in attendance. Alma’s daughter wrote the obituary for the newspaper. Next spring, ideally when we can meet and talk together, the six friends will organize a memorial service where people can speak about their memories of Alma. We are sure there will be many speakers, some serious and at least as many humourous.