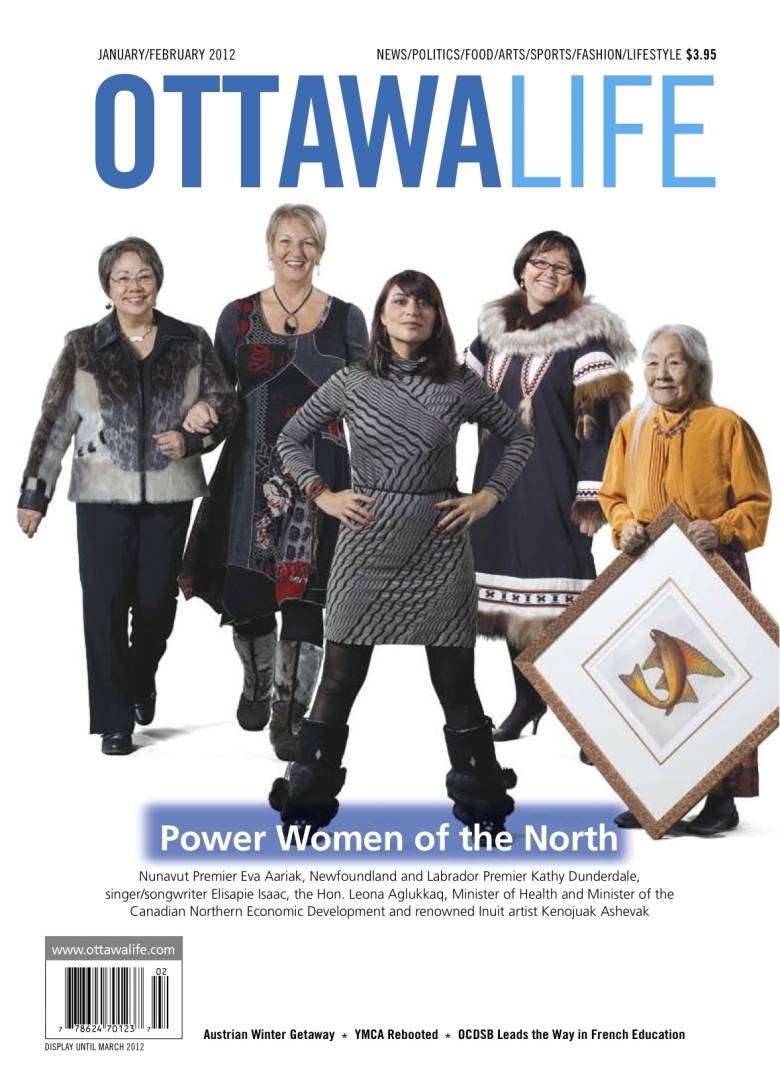

Arctic Series: Power Women Of the North

As we move into 2012 , Canada’s North is in the hands of women. Northern Premiers, Kathy Dunderdale of Newfoundland and Labrador and Premier Eva Aariak of Nunavut now preside over a huge chunk of Canada’s oil, gas and mineral reserves. In natural resource-dependant Canada, this means that while Dunderdale and Aariak are guiding the fortunes of the North, they also have a hand in the success of Canada as a whole.

On the surface, these two key premiers couldn’t be more different. Dunderdale is a warm, go-getting Newfoundlander born and raised on the Burin Peninsula (known locally at “The Boot.”) Prior to becoming the province’s first female premier, Dunderdale served as Newfoundland and Labrador’s Minister for Natural Resources (see page 31 for a full profile).

Aariak is a former CBC reporter turned politician and academic who became the first Languages Commissioner for Nunavut. Her diminutive stature and soft-spoken demeanour belie a steely determination. An Inuk born in Arctic Bay in the Northwest Territories, Aariak was the only woman to be elected to Nunavut’s Legislative Assembly in the 2008 election. Dunderdale is a Progressive Conservative. Aariak, an Independent, has no official political affiliation.

What unites these two disparate power women is their love of the North and the massive tasks ahead of them.

As it turns out, female power is strong in the North. There are, of course, the two female premiers, but there are many other women of influence. There is former Premier of the Northwest Territories, the Hon. Nellie Cournoyea, Chair of the Kativik Regional Government Maggie Emudluk, the Senior Negotiator for the Nunatsiavut Government, Isabella Pain and President of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, Mary Simon. And of course, there is the federal Minister of Health, the Hon.Leona Aglukkaq, who works in tandem with Dunderdale and Aariak, as the Minister Responsible for the North, Minister Responsible for the Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency and as the MP for Nunavut.

Some powerful private sector women are adding their economic muscle to the North. Take thirty-something Zoe Yujnovich, President and CEO of Iron Ore Canada – Canada’s largest iron ore producer. IOC employs almost 1900 people and directs colossal operations in Newfoundland, Labrador and Quebec. In 2008, IOC earned a handy $1.8 billion in revenue.

Northern women may be in charge but they also have big issues to face. How will they end Northern poverty? How will they turn the North from a poor country cousin to an economic powerhouse? How will their decisions influence Canada as a whole? There is no doubting the richness of the North. But there are overwhelming barriers to accessing that wealth – a lack of infrastructure, a lack of local expertise and grinding poverty. Then there is the question of governance, a need for Northerners to not only access their natural resources but to profit from them too.

The potential, however is huge. The North is the home of Canada’s collective psyche – the place of Canada’s dreaming. Think of the North and Arctic wilderness, polar bears, walruses, belugas, Inuk shuks and the rich cultural heritage of Canada’s First Nations and the Inuit all jump to mind. Secondly, mining exploration has unveiled Northern wealth – natural gas, shale, cobalt, gold and diamonds, not to mention oil.

In fact, between Dunderdale and Aariak, they preside over a sizable chunk of Canada’s oil, mineral and gas wealth. Newfoundland and Labrador produces around 40 per cent of Canada’s conventional light crude oil and 12 per cent of Canada’s total production of all types of crude oil. Hibernia, Newfoundland’s biggest offshore oil platform, alone pumps out 130,000 barrels of crude a day. Other Newfoundland natural assets include iron ore, with estimated reserves of 10,000 million tons, nickel, copper, gold and zinc and of course hydroelectricity.

Nunavut’s reserves, at 323 million barrels of crude oil, are equally impressive. The Territory contains 10 per cent of Canada’s oil reserves (more than $1 trillion worth), more than 20 per cent of its natural gas and a potential wealth of gold, diamonds, copper and nickel. But despite this, Nunavut has no oil production and mining is limited. A punishing climate and poor infrastructure make extraction difficult. Canada’s most Northern territory struggles to provide electricity to its citizens, let alone pump out inaccessible Arctic oil.

Aariak’s obstacles seem over-whelming. Nunavut has Canada’s largest population of young people. A third of the population is 15- years-old or younger and the high school graduation rate for Inuit in Nunavut is 25 per cent. Homegrown doctors, lawyers and teachers are in short supply and road connections are limited. A mere 850 kilometres of road services two million square kilometres — a fifth of Canada’s land mass. One winter road links Western Nunavut from the Northwest Territories. Nunavummiut (the name for residents of Nunavut) men die 10 years earlier than the average Canadian man. Women die 12 years earlier. Infant mortality, the death rate for infants under the age of one, is double the national rate. The cost of living is high. In Iqaluit, Nunavut’s capital, for example, two litres of milk costs $7.00.

The irony is that Nunavut’s poverty is in the midst of plenty. The challenge is how to get at the plenty. For Aariak, the answer is devolution (a handover of federal powers to Nunavut) and improving infrastructure

As a territory, Nunavut’s decision-making powers are funded by transfer dollars from the federal government. To a large extent, the feds get to call the shots. Give Nunavut’s population control over its destiny, Aariak maintains, and it can overcome anything. For now, Nunavut is hamstrung and the effects are manifold. The Inuit have massive oil reserves but they cannot fully profit from them. They want to build roads but need permission. They want to build infrastructure but they have funding caps. The list goes on.

“Nunavut has a lot of potential especially in minerals but the final decision as to when, how and what goes on in Nunavut is still being answered by Ottawa,” says Aariak. “We do not have dissolution yet, and that would help us be self-reliant and self-sufficient.”

Wrestling control of Nunavut from Ottawa is a tall order. Aariak’s job as head of the Government of Nunavut is to negotiate (along with Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated, an Inuit-owned and run corporation) with the federal government for full devolution. This includes a transfer of the Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development’s Northern Affairs Program, fiscal benefits and importantly, a resource revenue agreement. The agreement would allow Nunavut to tap into its natural resources base and actually benefit from it. For now, the federal government receives all royalties from non-renewable resource development (aka mining) on federal Crown lands in Nunavut. Devolution would make Nunavut the primary beneficiary of its resource development. For her part, Minister for Northern Affairs Leona Aglukkaq says that the Government of Nunavut and Nunavummiut “already has a significant voice in the management of lands and resources in Nunavut.” The Nunavut Land Claim Agreement means Inuit receive resource royalties. Co-management boards also “ensure guaranteed representation from the Inuit and the governments of Canada and Nunavut,” But she says “as a Northerner and as an Inuk, I favour devolution. However, in order for devolution to be successful and for the Territories to thrive, it must be done correctly so it can be sustained and benefit the people.”

Clearly, there are barriers for Aariak to overcome before the feds will devolve, namely the willingness of the government to let go. In the government’s 2007 Mayer Report on Devolution, author Paul Mayer, the Senior Ministerial Representative for Nunavut, stated “Nunavut faces significant operational, financial and social challenges that raise serious concerns over the Government of Nunavut’s ability to assume additional responsibilities.”

In fairness, the situation is not perfect. Mayer did identify particular issues of concern. The Baffin Regional Hospital in Iqaluit did not pass an accreditation review and a 2006 consultant report indicated that the Government of Nunavut had mismanaged the annual summer sealift since 2000, the same year the federal government devolved the responsibility. However, arguably, those are merely bumps in the road. For advocates of devolution, the issue is clear cut. Devolution would put money into the hands of Northerners to overcome geography (infrastructure), society (poverty and education) and government issues. And despite the hiccups, the competence is there. With women like Aariak at the helm, it is high time Northerners took charge of their own affairs. It is time the federal government stopped its double talk. The Department of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development says it is working for “a future in which First Nations, Inuit, Métis and northern communities are healthy, safe, self-sufficient and prosperous – a Canada where people make their own decisions, manage their own affairs and make strong contributions to the country as a whole.” And yet, the federal government continues to stall.

Mary Simon, president of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami agrees with Aariak that the foot-dragging has to stop. Devolution is the key to Inuit prosperity not just for Nunavut but for all of Inuit Nunangat. Inuit Nunangat includes the territory of Nunavut, the northern third of Quebec in Nunavik (which means “place to live” and the coastal region of Labrador in Nunatsiavut “our beautiful land”) as well as Nunatukavut (“Our Ancient Land”) and various parts of the Northwest Territories (mainly on the coast of the Arctic Ocean.)

While full devolution is critical, the North also needs adequate infrastructure to access its natural wealth. The task of equipping Nunavut alone is immense. Most of Nunavut lies north of the Arctic Circle. Its 25 remote communities are not linked by roads, there are no ports and no railroad. Each community needs separate infrastructure – schools, sewage, water systems and electric diesel power generators. Given the slim operational budgets of many Northern governments, private sector cash is needed to develop the North. That is where the 3Ps (public-private partnerships) come into the picture.

Several 3P projects are in the works to make Nunavut, Nunavik and Labrador more accessible by air, sea and road. Once completed, they will increase North-South business traffic, improving the quality of life of Northerners. Three projects stand out – a new airport terminal in Iqaluit, marine infrastructure projects in Nunavik and the Trans Labrador Highway (TLH.)

Improvements to Iqaluit airport are particularly important. Classified as an airport of entry into Canada, Iqaluit hosts scheduled passenger services from Ottawa, Montreal, Rankin Inlet and Kuujjuaq. Currently there are 21 flights a week between Ottawa and Iqaluit. But the airport is tiny. It has one main runway, three gates, one baggage claim belt and 30 parking spaces. A new $40 million terminal building – funded in part with private sector funds – will help Iqaluit deal with passenger volumes expected to double from 115,000 per year in 2009 to 220,000 in 2020. Nunavik, which is made up of fourteen fishing communities on the coast of Northern Quebec, will also benefit from a 3P cash injection. To facilitate fishing, Makivik Corporation, an Inuit organization (Makivik means “rise up” in Inuktitut), entered into an agreement with the federal government to upgrade marine infrastructure facilities.

To strengthen North-South business, Canada’s two most Northern Chambers of Commerce will hold the North’s largest exposition in Ottawa next month. Northern Lights 2012 will involve 150 exhibitors, workshops and displays to emphasize the economic and social links between North and South, and Ottawa in particular. Ottawa is a vital link in the North-South business chain. In 2009, imports to Nunavut (much of which flowed through Ottawa) totaled

$1.1 billion dollars.

North-South trade and 3P projects are key to tapping Northern riches. Aariak says “our challenge is that we need to improve our seaports and our airports and 3P projects assist with this. For instance, our fishing industry is becoming more and more popular and busy. But our fishermen have to travel all the way to Greenland to offload because we do not have the capacity in Nunavut so that is extra time. Our fish are being enjoyed in fine restaurants in Boston and New York, but we are not getting the full benefit of this.”

On the other side of Canada, Dunderdale faces similar challenges. Turning Newfoundland and Labrador from a “have not” province to a “more than has” province depends largely on infrastructure. Since the collapse of the cod fish industry in the 1990s, Newfoundland has looked to oil, gas and hydroelectricity to reverse its fortunes. New infrastructure from roads to ports to airports is needed to attract and keep mining investment.

Dunderdale’s first budget poured $1 billion into infrastructure including $216.4 million for road and bridge improvements. The federal government topped up this amount with an extra $35.2 million.

One of those projects, the extension of the Trans Labrador Highway – the main primary road which links Goose Bay, Labrador to Quebec – is expected to boost business activity in the province. The extension will dramatically cut travel times on the route and freight charges will drop

50 per cent ($330 versus $723) to ship 1.5 tons of freight from St John’s to Happy Valley. Travel costs and times between Montreal and points north of Port Hope Simpson will also be lower.

Investment in infrastructure de-finitely pays off, attracting business and industries. Companies such as Iron Ore Canada are greatly benefiting both Quebec and Newfoundland and Labrador. Iron Ore alone is injecting millions into the economies of both provinces and with extra infrastructure like the Trans Labrador Highway available, more businesses are sure to expand or establish a presence. (In March 2011, Iron Ore Canada invested $289 million into a second phase expansion to increase iron ore in Labrador.)

Isabella Pain, Senior Negotiator for the Nunatsiavut Government, has definitely seen how the mining sector can boost local economies in Labrador. Pain helped ensure benefits accrued to Labrador’s Innu and Inuit in negotiations with Vale Inco, the world’s second largest producer of nickel. Pain helped ensure Vale Inco’s Impact Benefits Agreements included hiring quotas of Innu and Inuit during construction and operations.

Pain was well prepared for negotia-tions with the mining giant. She was the Chief Negotiator on the Labrador Inuit Land Claim that was ratified in 2005 which set out the land claim rights of Labrador Inuit. Twenty-eight years in the making, the claim defines land ownership and resource sharing in the Labrador Settlement Area – 72, 500 square kilometres of land in northern Labrador. (Nickel was discovered near Labrador’s Voiseys Bay in 1993.) Under the agreement, Labrador Inuit own 15,800 of this land space and are entitled to 25 per cent of provincial revenues from future development in the lands

With mining companies like Iron Ore Canada and Vale Inco Limited injecting cash into Newfoundland and Labrador, the province’s green energy plan and massive infrastructure investments, the once “have-not” province is fast becoming a “more-than-has” province.

What could possibly hold Northern women back? “There are questions being raised that we don’t have the answers to yet,” says Dunderdale. “We don’t understand why the cod fisheries failed in our province….certainly the water temperature and salinity is being affected and we are seeing caribou herds in decline.” And, of course, climate change is affecting conditions. “Northern transportation depends a great deal on ice and snow and if the weather is mild, it impacts people’s ability to travel. We are seeing signs of climate change and at this point, we don’t have a handle on it.”

But with strong Northern women like Dunderdale and Aariak at the helm, it won’t be long until they do.