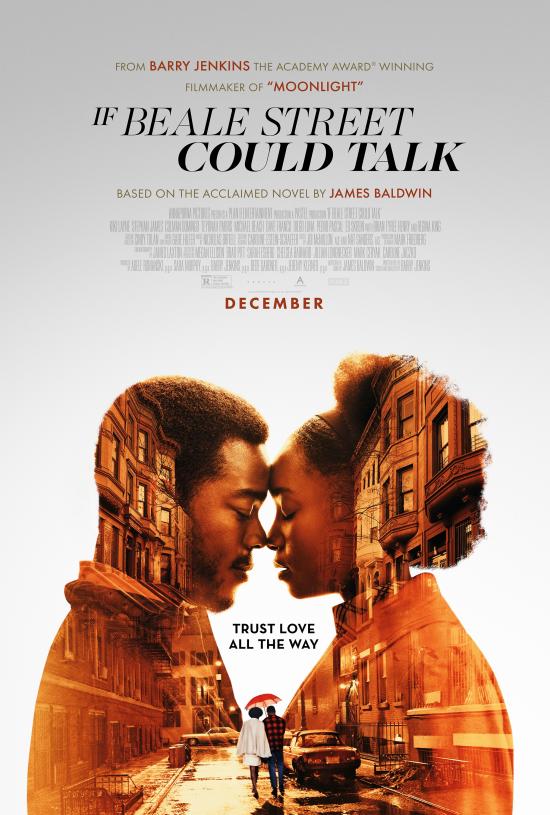

Barry Jenkins’ If Beale Street Could Talk is a mesmerizing adaptation of the 1974 book

By Asma Horea Abdourahman

Director Barry Jenkins’ adaptation of James Baldwin’s 1974 book, “If Beale Street Could Talk”, opens up with a quote from the late author: “Every black person born in America was born on Beale Street, whether in Jackson, Mississippi, or in Harlem, New York. Beale Street is our legacy.” In this opening sequence, Beale Street becomes more than a place, but a collective experience shared by black Americans. And so, we arrive in Beale Street where 19 year old Tish (played by newcomer Kiki Layne) is visiting her childhood friend and lover, Fonny, who was recently arrested for the rape of a Puerto Rican immigrant named Victoria Rogers. We follow Tish, as she and her family come to terms with her first pregnancy. The father of her child, Fonny, played by Scarborough native Stephan James, is incarcerated for the rape of Rogers. Although Fonny has an alibi, he and his loved ones are tasked with proving his innocence in a corrupt American justice system. The plot segmentation closely follows that of the book, disregarding a chronological timeline and is constantly ever-changing. The first half of the film heavily relies on Tish and Fonny’s romance, but as the story unfolds, the more heartbreak and helplessness we come to feel.

In Beale Street, there is love and that is what finds itself at the forefront of the story. The films’ most compassionate moments happen between mother and daughter, sister and sister, and father and daughter. Tish’s family sees to it that Fonny’s love is not confined to a jail cell for a crime he did not commit. Moreover, although we see many themes born out of our sour world, they mostly serve to echo the narrative of love in a desolate place, or in Baldwin's words, “…trusting love all the way.” Characters in passing; waiters and shopkeepers alike, appear from time to time to protect Tish and Fonny from cruel actualities of the world.

The story is brutal, the visuals are not; James Laxton’s cinematography makes sure of this. We see an unrelenting amount of empathy for the characters of the film, observed in the delicate ways Tish and Fonny hold one another or appear on screen, backlit like heavenly beings. They stare at the camera longingly, inviting us to become part of their families. At times, it even felt as though Jenkins would want to hold onto some tender moments in the film; so much so that he would neglect or even run away from some of the harsher realities we should have seen. The film was almost in a race against time to do justice to the weight of Baldwin’s words.

Perhaps, these were the easier, less complex themes to underscore when referring to Baldwin’s book, although Jenkins does attempt to include it all. Fonny’s childhood friend, Daniel played by a knockout Brian Tyree Henry, delivers one of the most heartbreaking monologues in the film by describing the two years he spent in jail for a crime he didn’t commit. Holding back tears, he recounts how it felt to be at the mercy of a corrupt system that had no plans on empathizing with the likes of a young black man. The pain lingers as the audience digests his words, listening as he helplessly recounted how years of his life taken from him for no reason other than the colour of his skin.

Regrettably, the issue of sexual violence in an age of #MeToo remains underdeveloped and only briefly acknowledged. The audience, who we should assume did not read the book, still have room to doubt Fonny’s innocence, which presents itself to be dangerous when we are simultaneously hoping for his acquittal. We know Fonny didn’t do it, but instead of hearing the objective truths of what happened that night, we hear a character say, “[I’ve] known him all my life,” invalidating the victims’ experiences as a survivor and echoing familiar lines uttered in defense of public figures recently accused of sexual assault.

As black men continue to be falsely incarcerated as they were many years ago, and women are still struggling to be believed, Beale Street finds itself in an interesting middle ground. It puts two truths at odds, but does not make you chose one or the other. Had the film dedicated more time to exploring the corrupt legal system and offering more sympathy to Victoria, it would have felt as if both characters’ stories had received their due justice. Audiences would have a better understanding of the corruption that comes with mass incarceration, without muddying the lines of a rape survivor’s truth.

Baldwin wrote of a love that stayed gentle and true while existing in a bitter, cold world. In turn, Jenkin’s homage to Baldwin, or as he chose to call him at the end of the film, Jimmy, seems to have done exactly what the characters had been trying to do all along; that is, preserve Tish and Fonny’s enduring care for each other despite the crushing odds against them. The film is full of contradictions that are simultaneously true. Though it is painful and upsetting, there are moments of laughter, and reassurance. Joy sits beside sadness. Hope can live, even when the threat of injustice lingers. If Beale Street Could Talk achieved something rare, it presented us with some of the most beautiful moments in life, born from some of our world’s worst horrors, and made them seem much more important.

If Beale Street Could Talk is now playing at the ByTowne Cinema.