Can Canada Keep Its Cars and Save Its Canola?

Why Carney’s Diversification Strategy Demands a Rethink on EV Tariffs

Prime Minister Mark Carney entered office promising to rebuild Canada’s credibility abroad and its competitiveness at home. Last week, in response to sweeping tariffs imposed by Donald Trump on Canadian autos, Carney declared that Canada must “diversify its trade relationships” and avoid overreliance on any single partner. “We cannot allow our economic future to be held hostage to political whims outside our borders,” he said in Toronto. The message is sound—but the execution will determine whether Canada protects its core industries or stumbles into another cycle of reactive policymaking.

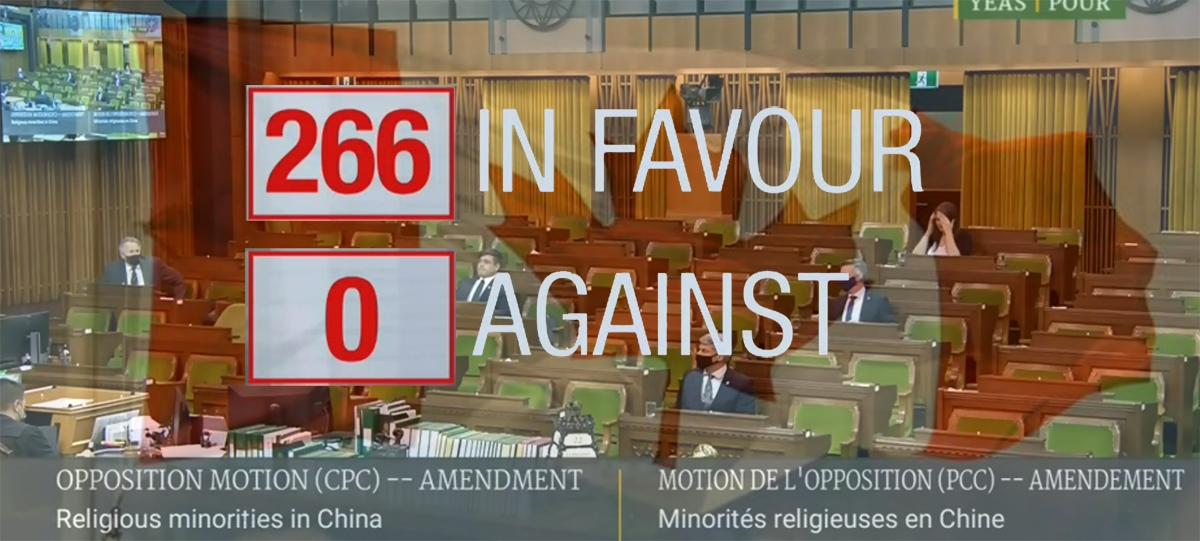

Few sectors illustrate this dilemma more starkly than canola and cars. According to the Canola Council of Canada, the canola industry contributes roughly C$43 billion annually to the economy and supports about 200,000 jobs nationwide. Direct exports of seed, oil, and meal are worth around C$14 billion a year. China alone purchased nearly C$5 billion of Canadian canola products in 2024, making it our largest offshore buyer. When Ottawa retaliated against Trump’s auto tariffs with its own duties on Chinese EVs, Beijing struck back—slapping provisional anti-dumping duties of 75.8 percent on Canadian canola seed and 100 percent on canola meal and oil. Futures prices plunged by 6.5 percent almost overnight, pushing prairie farmers into crisis.

Yet Ottawa’s auto tariff regime offers little protection to consumers or industry. Canada’s EV mandate—requiring 60 percent of new car sales to be electric by 2030 and 100 percent by 2035—may look ambitious on paper, but few experts believe it is remotely realistic under current conditions. The country lacks a national charging infrastructure outside a handful of urban corridors. Range anxiety and poor cold-weather performance remain barriers in a country where winter dominates half the year. Meanwhile, Canada has not built the mining and processing capacity needed for the rare earth elements essential to EV motors and batteries.

China, in contrast, has spent the past two decades constructing a vertically integrated supply chain. From mining and refining neodymium, dysprosium, and terbium, to processing and manufacturing advanced EV motors, Beijing has positioned itself as the indispensable player. Canada, meanwhile, is only beginning to chart its course. It sits atop world-class deposits—most notably the Nechalacho (Thor Lake) project in the Northwest Territories, which contains 192.7 million tonnes of measured and indicated resources, including more than 636,000 tonnes of neodymium-praseodymium oxide. In Saskatchewan, the newly established rare earth processing facility led by the Saskatchewan Research Council is expected to produce enough material to support the manufacturing of 500,000 electric vehicles annually by the end of 2025. These are promising developments, but they remain early steps. Canada’s critical minerals strategy is still in its infancy, and the scale of production and integration required to meet Ottawa’s ambitious EV and clean energy targets is nowhere near the scale required to meet Ottawa’s lofty EV targets-or any targets for that matter.

But therein lies the real opportunity. Instead of doubling down on punitive EV tariffs, Canada should explore partnerships with Chinese EV companies—BYD, NIO, and others—that are already forming joint ventures with Western automakers in Europe. Imagine a model where Chinese firms co-design, produce, or assemble EVs in Canada. The result would be lower prices for consumers, more investment into domestic supply chains, and thousands of new Canadian jobs in assembly and research. In exchange, Ottawa could secure guarantees on agricultural trade—creating the conditions for Beijing to lift its canola tariffs.

This is not capitulation; it is a win-win strategy. Europe has already demonstrated that engagement with Chinese EV makers can yield both affordable vehicles and industrial cooperation. Canada, with its resources, engineering expertise, and access to the U.S. and Mexican markets, is uniquely placed to adapt this model. Doing so would give Canadian farmers back a multi-billion-dollar export stream while ensuring that auto workers are not sacrificed to an unworkable mandate.

Carney’s credibility rests on whether he can turn rhetoric into policy. His call for diversification cannot simply mean shifting exports from one customer to another while relying on tariffs as a blunt instrument. True diversification means aligning Canada’s strengths—our resource base, innovation, and agricultural productivity—with the global industrial realities of the 21st century. It means recognizing that EVs are not just about climate targets, but about supply chains, minerals, and manufacturing partnerships.

The choice before Ottawa is stark: stick with protectionist instincts and watch as prairie farmers and auto workers both absorb the fallout, or embrace a smarter path of collaboration that keeps our canola and secures our cars. The time to act is now, before protectionism hardens into policy and opportunity slips away.

Photo: iStock