Canada: Apartheid Nation in Review

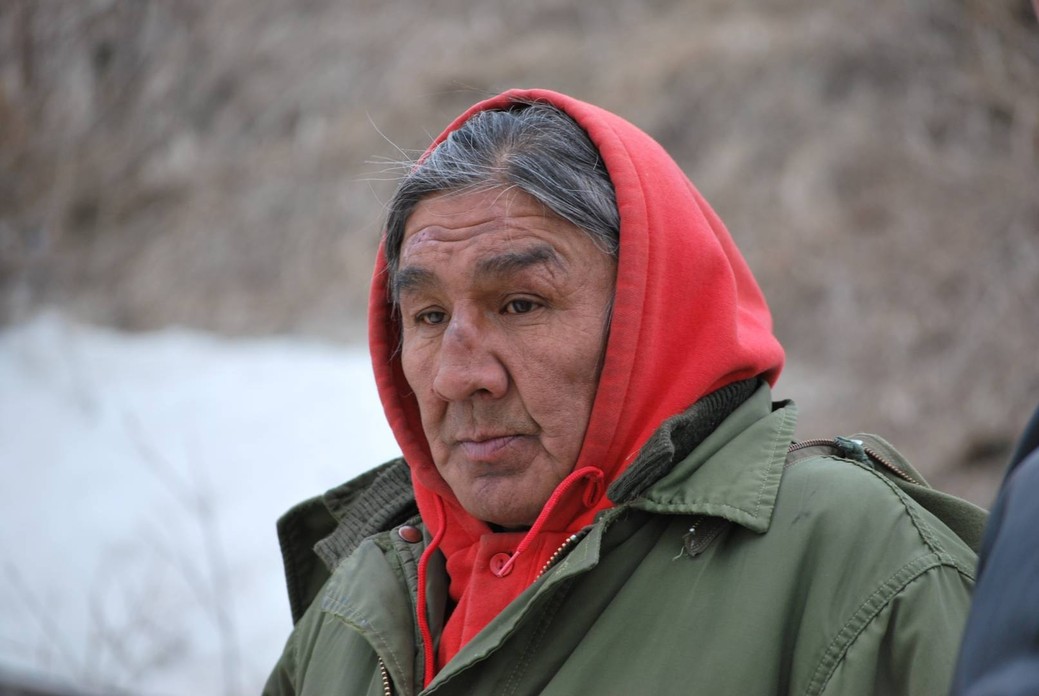

Faced with extreme poverty and a harsh climate, the remote, decaying and polluted northern Ontario aboriginal community of Attawapiskat has become a national cause célèbre, one month after the Ottawa premiere of a 26-minute documentary entitled Canada: Apartheid Nation, which depicts the plight of the inhabitants of this depressed community on the desolate western shore of James Bay. The screening – held in the Auditorium of Library and Archives Canada on October 26th – was co-sponsored by the Canadian Film Institute and Ottawa Life Magazine.

The lack of appropriate weather-resistant housing in Attawapiskat as winter settles in has prompted community leaders to declare a state of emergency, a move that has since attracted saturation media coverage and belated federal government attention. The Red Cross is delivering emergency blankets and heaters to those living in substandard housing. Sadly, Attawapiskat is but one of many such remote aboriginal settlements that one would expect to find in the Third World, and not in a “caring and compassionate” First World nation such as Canada.

A recent selection at the Toronto Indie Film Festival (which runs alongside the Toronto International Film Festival), Canada: Apartheid Nation exposes the truth about horrendous living conditions in remote northern First Nations communities: Third World conditions in a First World country. While living next to one of the richest diamond mines in the world, the community of Attawapiskat faces poverty, homelessness, despair, pollution, substandard education and decaying infrastructure, according to director Angela O’Leary and producer Laurie Stewart for Sagesse Productions of Ottawa.

The Attawapiskat First Nation is representative of the product of an archaic federal government department of ‘Indian’ Affairs: the filmmakers claim that the department’s policies systemically discriminate against Canada’s First Nations peoples. However, there are heroes from within the aboriginal community (from children to Chiefs) who are working quietly and surely to effect great change, no longer expecting help from Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC).

Dan Donovan, publisher of Ottawa Life Magazine, introduced the film to a packed house:

“After this fantastic short film by Sagesse Productions was premiered at the 2011 Toronto Indie Film Festival, audiences were perplexed, shocked, stunned and saddened by its depiction of the dreadful living conditions in Attawapiskat, a remote Cree community on the eastern shore of James Bay in Northern Ontario. Once I saw Canada: Apartheid Nation, I wanted to do whatever I could to get it out there, as the plight of Canada’s aboriginal community is extremely distressing and attention should be paid. Angela O’Leary – a very successful businesswoman and entrepreneur in the high-tech field – approached Ottawa Life Magazine and asked if we could help her promote Canada: Apartheid Nation. Ottawa Life had been running a series on Aboriginal Pathways for the last year and a half and was only too happy to oblige. I was also quite intrigued that this businesswoman would go to such a remote community in the middle of winter and put this film together.

“The distressing fact of the matter is that in this country, aboriginal people are living in Third World conditions,” Donovan continued. “Over 40% of Canada’s aboriginal population does not have access to safe drinking water. The highest suicide rates in the country are in aboriginal communities. There is still a very paternalistic attitude towards the aboriginal community… indifference on the part of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, or an attitude of – out of sight, out of mind. The Auditor General of Canada has said repeatedly that the solution to this problem is getting rid of the department of Indian Affairs, which has an annual budget of $18 billion and is mostly staffed by white guys. Trouble is, these guys aren’t doing their jobs – and they are being very well paid not to do their jobs. So power should be transferred to Canada’s aboriginal community to take responsibility for their own affairs.

“It’s obvious from this film that there are some people who care, but caring isn’t enough,” Donovan summed up. “We need to collectively demand change and accountability. People at Indian Affairs need to be removed if they are not doing their jobs. Here we have an $18-billion-a-year department, and yet many of the people INAC is supposedly responsible for have been living in abject poverty for decades.”

Director Angela O’Leary attended the screening to introduce and discuss her film.

“As Canadians, we stand up for people all over the world – we stand up for human rights,” O’Leary said. “It’s a Canadian trait that we’ve embraced and this is all very well and good. We feel strongly about helping those in other countries but have we forgotten about our own fellow citizens? Do we feel it is acceptable to neglect our own people? We build schools in Afghanistan but won’t build them on aboriginal reserves, which must wait months – and often years – to receive funding approval from Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. I recently interviewed Cindy Blackstock, executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada. She posed a really important question: ‘Are we willing to trade off buying fighter jets and organizing expensive international summits to provide all our people with equal access to health care, education and clean water?’ I sincerely hope the film will shed some light on this question… the most pressing issue of our time.”

For more information, visit http://www.canadaapartheidnation.com/.