Canadians are staring into a debt abyss

by Greg MacDougall and Steve Saunders of Government Analytics

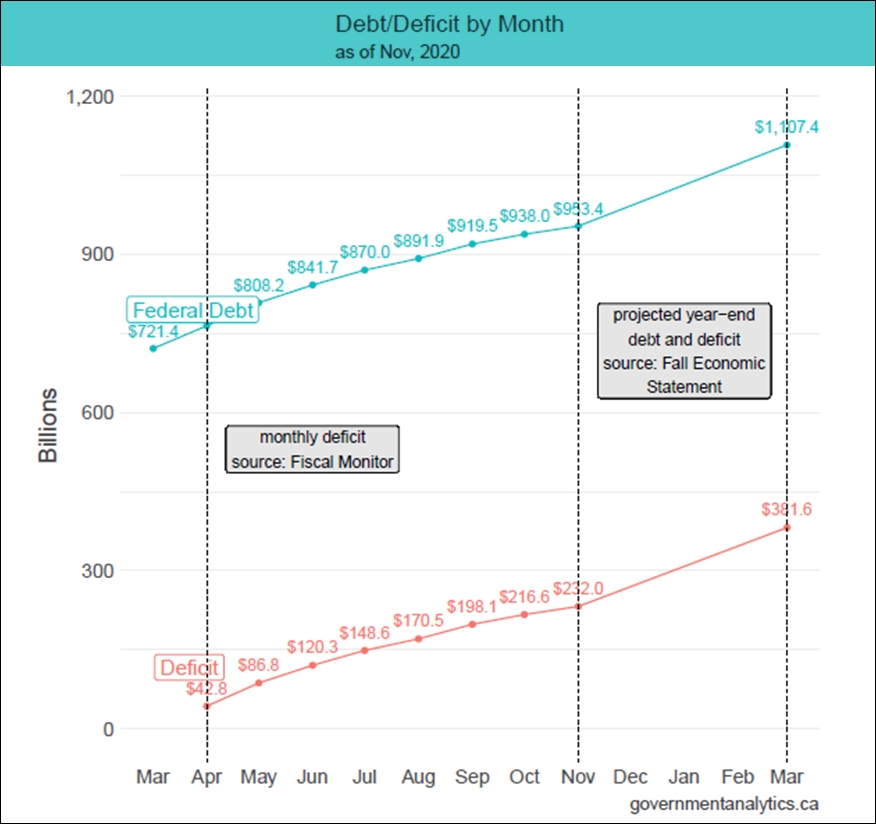

While Covid-19 hit the Canadian economy like a sledgehammer last March, its impact can now be likened to that of a slow motion 1998 Ottawa Ice Storm or 2013 Calgary flood; it’s not simply a phase of the business cycle or shock to financial markets. In pre-Covid February 2020, the Department of Finance’s monthly Fiscal Monitor reported a budgetary surplus of $3.6 billion. The unemployment rate was 5.6 per cent across the nation, and Canada entered that month with four coronavirus cases. A month later, general lockdowns began, and the deficit exploded; $14.8 billion in red ink in March, and a combined $86.8 billion for April and May, the first two months of the new fiscal year (FY) 2020-21.

A year later, Covid cases are approaching 820,000 with more than 21,000 Canadians dead from the virus. While the economy has emerged from the coma it entered last spring, specific sectors such as travel, tourism, airline travel, hospitality and arts and entertainment remain moribund. Overall GDP growth this year will contract by 5.8 per cent. The Bank of Canada projects growth of about 4 per cent in 2021 as vaccine campaigns are anticipated to accelerate, and close to 5 per cent in 2022.

While many Canadians remain confused about the rationale behind what’s open and what’s closed – big box store good, Mom and Pop store on Main Street bad – and divining the rules governing shopping for non-essential items at essential stores without the aid of a Rosetta Stone, there is no confusing the state of federal finances; we are in unprecedented territory.

So how bad are the deficit and debt numbers? Canada closed the books on the 2019-20 FY with a deficit of $39.4 billion; relatively small in the context of a G-7 economy, but still jarring given that Canada was nearly a decade into economic expansion following the 2008-09 financial crisis. Truly prudent economic stewardship would have seen the government running, at the least, small surpluses. It bears repeating that in losing the 2015 election to Justin Trudeau’s Liberals, the Harper government bequeathed a balanced federal budget.

Our $39.4 billion deficit last year has decupled (X10) to $381.6 billion as projected in the Fall Economic Statement. In lock-step, the accumulated federal debt has galloped from $721.4 billion to a projected $1,107.4 billion – or in layman’s terms, more than $1.1 trillion. This figure does not include an additional $70-100 billion in stimulus that the government has indicated it will spend over the next three FYs. The government will also amend the Borrowing Authority Act to pump up the limit on borrowing to $1.831 trillion; 50 per cent higher than the previous limit which was eclipsed earlier this year as Parliament approved emergency spending powers in order to deal with the crisis.

In a report released on February 18, 2021, the Conference Board of Canada wrote, “Federal and provincial/territorial governments have borrowed massively to support household incomes and businesses through the COVID-19 pandemic. Rock-bottom financing rates will help governments manage the near-term financing challenges associated with the additional debt burden, but the ramifications of this massive and sudden buildup in public debt are inescapable over the longer term.”

This new debt burden is truly generational. This past November, the Parliamentary Budget Officer released an update to his Fiscal Sustainability Report 2020, with a Supplementary Data Set. After crunching this data set, Government Analytics estimates that barring tax increases or significant program cuts, the principal on the federal debt will not begin to be paid down until 2061. College and university graduates of the class of ’21 will be pondering retirement by that time!

As is the norm, the federal government has financed this massive fiscal response and attendant deficit, with the sale of Government of Canada bonds. What is different this time is that rather than bonds remaining recorded on the balance sheets of financial institutions such as commercial banks, the Bank of Canada buys these bonds from for instance, the chartered banks on the secondary market. The Bank then creates electronic deposits with the chartered banks – termed settlement balances – which the banks in turn lend out to their customers.

Quantitative Easing (QE), this process of internal banking industry sausage-making, coupled with the Bank’s overnight interest rate of 0.25 per cent, is also tied to the Bank’s inflation goal which is to maintain inflation within a narrow band of 1-3 per cent annually, with 2 per cent being the sweet spot. While high inflation as witnessed in Canada during the 1970s and early 80s is destructive, a lack of inflation or deflationary pressures in the economy is also troublesome.

Through QE, the Bank of Canada has bought more than $300 billion in Government of Canada bonds since March 2020. Prior to Covid, the Bank held just $76 million in government bonds. Overall, the balance sheet of the Bank of Canada has grown from about $120 billion in March 2020 to $548 billion in December 2020. And the Bank will continue to buy $4 billion a week in government bonds for the foreseeable future.

So, should we be worried? Not according to the official line of the Government of Canada which is that given interest rates at historically low levels, such borrowing is sustainable. Counterintuitively, for the moment it is; with the government paying interest rates as low as 0.25 per cent (negative if we factor in inflation), charges on the federal debt actually fell this year. And as a percentage of GDP, public debt charges will only rise marginally from 0.9 per cent this year to 1.2 per cent by 2025-26.

And it was absolutely necessary that the federal government provide personal income payments, support provincial efforts to keep schools open, and respond to new pressures on the health care system. As confirmed by an IMF report this week, the federal response has been comprehensive, largely coherent, and alleviated the financial pain felt by millions of Canadians.

But the bill will come due. And the government’s calming projections rest on uneasy assumptions: that interest rates remain low; that stronger economic growth will continue past 2023 bringing employment levels back to pre-pandemic numbers; and that the economy is not subject to another shock in the medium term. Canadians also face profound questions related to the diminished role of Parliament, and the new and evolving pre-eminence of the Bank of Canada. We’ll explore these questions next week.

It is absolutely essential that Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland articulate a fiscal roadmap in the coming Spring Budget that projects prudence, and credibility, and inspires confidence in Canadians that the government can both manage the fiscal crisis, and the post-Covid recovery. As Dorothy said to Toto in the Wizard of Oz, “I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore.” We’re not but neither are we over the rainbow. We’re currently on a lonely highway with no guardrails, miles from home.

Greg MacDougall and Steve Saunders are partners in Government Analytics, an Ottawa firm that specializes in mining, analyzing and formatting government data so that it may be easily communicated for advocacy or corporate purposes. GA utilizes proprietary software to transform raw data into visualized, in-depth evidence.