Funding Scientific Research: Sometimes targeted research is the best approach, but not always

The huge concentration of scientific effort to create, verify and supply a vaccine to protect against Covid-19 and towards improved therapeutics for those who fall ill are perfect examples of appropriate targeted research.

Fans of novels or films about crime know that the iconic enablers of a crime are means, motive and opportunity. Well, the same dicta apply to the effective use of targeted research, in that targeting a specific practical research objective is only effective when there is means (enough money and research capacity), motive (defeating a deadly plague that also wrecks economies is an awfully good motive) and “opportunity”. In this case “opportunity” means that the preexisting knowledge base must be sufficient to achieve the goal in a useful time scale. In the case of a vaccine against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, the answer was pretty clear-cut, since eight commercially available vaccines for coronaviruses in animals already existed, including one for a beta-coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2 is a beta-coronavirus as well). So it seems massively likely in this instance that the targeted research effort will succeed, and be a boon to us all.

But there are plenty of examples of targeted research programs that didn’t do nearly as well as hoped. Nixon’s “War on Cancer” launched in 1971 was largely a flop, though a reasonable amount of good science did come out of it. But it was not an efficient way of getting that amount of good science done. Clearly in 1971, the “opportunity” was lacking, in that the fundamental understanding of cancer mechanisms and the biology behind them was insufficiently advanced to force a fast push to any revolutionary therapeutic breakthrough. The advances in molecular biology of the past 30 years may well now open those doors, but not the science of 1971. Most scientists of 1971 were critical of the rhetoric and funding approach of those targeted research objectives. One senior scientist who expressed skepticism of the Nixon plan was chided by a reporter, who said, “Well, we did set a target of going to the moon, and we got there”. The scientist replied, “Yes, but the “War on Cancer” is like hiring Columbus to go to the moon.” Given the preexisting knowledge base of 1971, he was right.

Today in Canada, most advanced scientific research is located in the universities. While some funding for university research comes from philanthropic sources and from research contracts with private sector entities, the importance of research grants from government has been paramount in the research successes of the second half of the 20th century and the first bit of the 21st. This is true in both Canada and the USA. In Canada, the three key federal research granting councils are the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC), the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR), and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSJRC). CIHR was formerly the Medical Research Council (MRC). These three research granting agencies have a total budget of well over $3 billion a year.

But in recent times the laudable pressures for accountability in government have generated a less desirable side effect. Politicians now feel the need to appear to be targeting research money to objectives that government has endorsed, and to reduce funding available to what they call “curiosity-oriented research”. This has fueled a huge drive within government to identify the strategic research topics that will play well politically, and to skew granting systems to favour them. This has led, understandably, to a reduction in resources accorded to basic research (derisively termed “curiosity-oriented research” by some), and a boosting of resources to “applied” or “mission-oriented” research. Hence, in recent years the resources of the three granting councils have largely been directed towards targeted objectives.

Furthermore, a non-trivial portion of that applied research is actually closer to development, rather than research on the “R and D” spectrum. And while promising applied research results should be advanced into a development phase, those development resources should not be subtracted from the research pool. Admittedly, Canada has a poor record of exploiting its own discoveries, which more often have reached the market via foreign companies, but the solution to the dearth of development or demonstration phases in Canada is not to steal resources from those allocated to the underlying research, but to foster an industrial strategy that better facilitates tech transfer to actual application.

As politically satisfying as this trend towards strategic targeting and mission-oriented research may be, it has a number of counterproductive aspects. Researchers applying for funding will, of necessity, distort their plan of work to cater to the articulated priorities of the government granting entities, shelving their best ideas for the moment. One must always be mindful that it is the researchers who have the ideas and the striking insights, and one cannot, from the outside, order them to have their insights on a particular topic. The ideas come from them. Consequently, the folk tasked with coming up with the applied thrust areas to be highlighted and supported are always somewhat removed from the front lines of idea generation, since they are either politicians or bureaucrats, though some of the latter group may be former researchers or researchers nearing the end of their careers. They will, of course, hit the occasional home run by promoting something that yields useful results easily, but they do not have as good a track record as the folk who actually submit the applications for research funding.

The myth that applied research has a bigger and faster payoff rate than basic research is not new. Almost half a century ago the United States Air Force conducted a deeply flawed study called "Operation Hindsight" to ascertain what types of research were the most useful. That study concluded that the momentum for critical advances in applied technology was the result almost exclusively of applied research and development. The authors claimed that the technological revolution, and the so-called Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA) owed little or nothing to fundamental, or curiosity-oriented research, which, according to them, normally had no practical use for at least 50 years.

Doubting the conclusions of that study, two great American medical scientists, Julius Comroe and Robert Dripps, conceived and executed one of the first large-scale research studies on the subject of research and discovery itself. Focusing on fields they knew, which were cardiovascular and pulmonary medicine, they undertook to learn what were the real antecedents of the 10 most critical practical advances in cardiovascular and pulmonary medicine of the period 1945-1975, including things we now take for granted, such as heart-lung machines. The international panels of experts that they conscripted to participate in this look back in time eventually identified some 1500 seminal discoveries which led to those ten critical advances, and followed the trail of discovery as far back as Andreas Vesalius, the famous Flemish anatomist who taught at Padua in the 1540's and Hieronymus Fabricius of Padua, who discovered the valves in the veins some 60 years later. They also identified 112 critical enabling discoveries, which they called "nodal points". And that is where it got interesting.

Comroe and Dripps discovered that over 40 per cent of the nodal points were pieces of basic, curiosity-oriented research, and another 20 per cent were discoveries made during applied research projects which had been intended to yield completely different results for application to completely different practical objectives.

Furthermore, they found that the time lag from basic research discovery to the practical application was sometimes very short. In almost 10 per cent of cases it was less than 12 months, and in 20 per cent was less than a decade. Their findings thoroughly debunked "Operation Hindsight".

Their widely disseminated, rigorous report and related writings transformed official attitudes in the United States and Canada in the late 1970’s, and was a significant factor leading to about 25 years of massive publicly funded support for fundamental research in both countries.

But today the communications revolution and the new approaches to conducting policy discourse gives the politicians and bureaucrats an incentive to appear to be “buying progress” in a strategically directed fashion. Regrettably, shopping for and buying something that does not yet exist is a tricky business. We will need to learn again that letting the folk with the ideas make the research proposals, and then funding the most convincing will always yield more than ordering people to have ideas on particular topics, especially when that ordering is being done by folk who have not recently had new ideas.

It is not the fault of the universities that their scholars are struggling with the difficulties presented by the need to fit their ideas to the Procrustean bed of politically targeted granting priorities. But it does diminish the capacity of the universities to build the house of intellect and to advance human knowledge. And I would charge that some universities have been too meek in pointing out the short-sightedness of the present trend.

I well recall a related incident in Canada from the 1970’s. At one point the official opposition in parliament was having fun with its criticism of the government spending by reading out in the House of Commons the titles (and amounts) of large numbers of government grants for university research projects in the social sciences and humanities which seemed pointless or humorous to them. And I must admit that some of the titles seemed hilarious. But whenever the title touched on a topic that I knew something about, the title seemed very cogent to me, and I could see instantly why it might be important to carry out such a study. At that time the opposition party’s health critic in the House of Commons was a friend of mine, and so I phoned him up and told him that while I enjoyed a good laugh as much as the next person, I feared that mirth over the grant titles being read out in the house conveyed more about the lack of knowledge of the members of parliament than it did about any silly or wasteful government expenditure. The readings of the humorous titles stopped immediately.

The people who govern us are not expected to know what is at the leading edge of every discipline. And they only make themselves look silly when they pretend to do so. Research is a risk activity. We can reduce that risk by vetting requests for funding very carefully to eliminate poorly thought out or unrealistic proposals, or proposals by researchers with poor track records. But we cannot reduce that risk by telling the innovators what ideas they should have.

Consequently, while a certain quantum of targeted research is clearly a damned good idea (like stopping a pandemic), using that approach for almost all of ongoing research funding is not. Universities need to band together to tell our political masters exactly that.

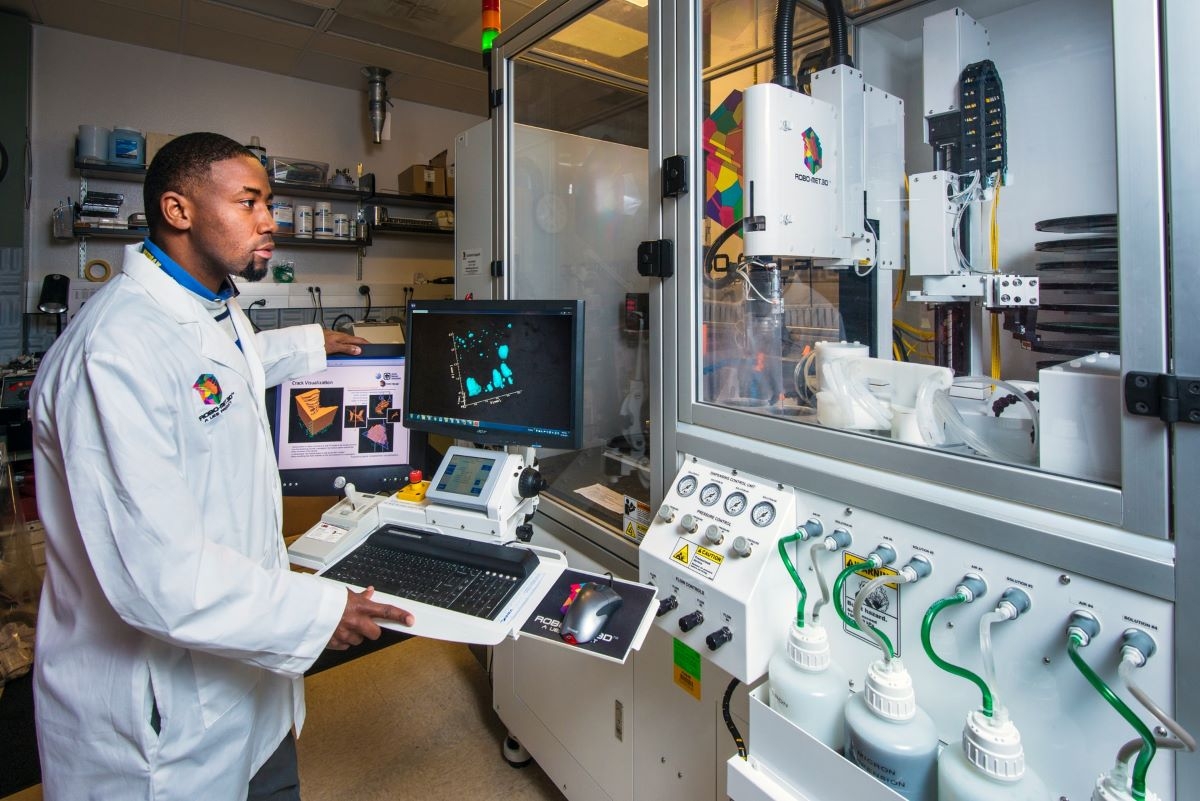

Photo: Science in HD on Unsplash