How Canada Can Encourage Positive Developments for the Belt and Road Initiative

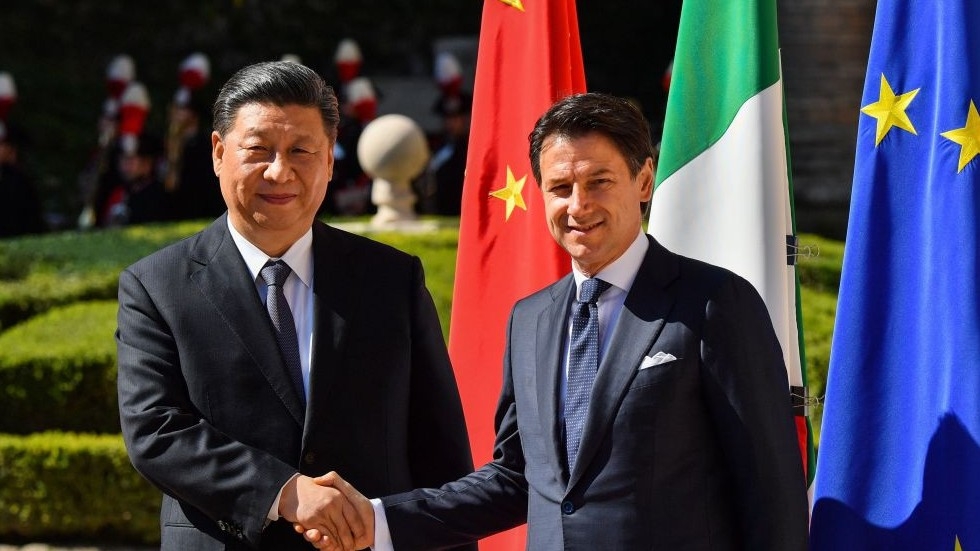

(Photo credit: Wang Chaoach)

China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is Chinese President Xi’s signature

China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is Chinese President Xi’s signature

foreign policy plan and is one of the most ambitious infrastructure and investment

efforts in history. The BRI began in 2013 to boost trade through investment in

ports, power plants and other infrastructure in more than 140 countries from Asia

to Europe and Africa.

In his response to my original article on China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Preston Lim deepens the nuance of his arguments regarding the dangers of debt-traps that the BRI poses, but ultimately still denounces the initiative as “empire-building” and urges Canada to stand firm in criticizing China’s practices. His arguments rest on two pillars. The first is that an international order led by the United States creates a positive-sum environment for the global community, whereas a China-led international order would subject the world to zero-sum practices, as exemplified through China’s use of “debt-traps.” Secondly, he argues that “not all money is good money” and that China’s reliance on “inequitable free trade agreements and onerous debt-repayment terms” could result in nationalist backlashes against China, and even regional instability in countries along the BRI. This article responds by demonstrating what true debt-trap behaviour looks like, as seen through the Third World debt crisis in the 1980s, dispelling the current myth of a universal anti-Chinese sentiment along the BRI, and emphasizing that engagement based on mutual respect can enable the Canada-China relationship to produce win-win results for both countries.

Lim endorses the idea that American foreign policy has tended to be positive-sum in nature, as opposed to China’s debt-trap diplomacy, which he portrays as zero sum. The first part of Lim’s claim is valid. US institutions and the US military has helped maintain overall macroeconomic stability, as well as freedom and security of navigation on the world’s oceans. These efforts have created a global business environment that promotes economic development across the world, especially in China after its opening up in 1979. However, history has demonstrated that this US-led order has also wreaked significant damage on non-Western economies. My previous article discussed the East Asia crisis of 1997-98, so this article will explore the Third World debt crisis of the 1980s. Ironically enough, this crisis stemmed from Western institutions engaging in the kind of debt-traps that Lim accuses China of practicing.

The Third World debt crisis emerged from the short-term profit maximizing practices of Western commercial banks, which pushed Third World debt to unsustainable levels. After the first OPEC oil shock of 1973-74, Western commercial banks swelled with cash as OPEC nations deposited their earnings. At the same time, the Third World was experiencing rapid industrialization built on an export-oriented growth model, as seen through the 7% average GDP growth per year for countries such as Brazil and Mexico. As their economies grew, these Third World nations began borrowing more in order to finance their growing dependence on imports of food, oil and capital goods. Sensing an opportunity to profit off such rapid growth, Western commercial banks flooded these developing nations with their newly-gained funds. However, they offered non-concessional loans with shorter maturities and market rates of interest, as opposed to concessional loans with lower interest rates and longer grace periods. By 1979, around 77% of Third World debt was comprised of non-concessional loans, compared to 40% in 1971. In other words, commercial banks saddled developing countries with unsustainable levels of debt. The reckoning came when the US Federal Reserve raised interest rates to around 20% to fight soaring inflation rates after the second oil shock of 1979. Third World countries could no longer afford to service their debts at these elevated interest rates. Beginning with Mexico’s default in 1982, multiple developing nations faced financial crises that forced their GDP growth into negative territory. To save their economies, these countries were forced to turn to the IMF, which imposed structural adjustment policies that came at the cost of soaring unemployment levels and the severe curtailment of public benefits. While the behaviour of these banks may not have been directly sanctioned by the US government, it is difficult to imagine the banks lent money without the assurance that the US government would bail them out if their loans failed, especially given the phenomenon of the “revolving door” between Wall St., the US Treasury, and the IMF as documented by the economist Joseph Stiglitz.[1] In other words, the Third World debt crisis illustrates how a US-led world order is just as capable of engaging in the zero-sum behaviour of setting debt-traps at the expense of other nations.

The Western media often cites the concession of the port at Hambantota, Sri Lanka, as evidence of China’s “debt trap diplomacy.” Yet the singular focus on this one example obscures the larger picture. The Washington-based think tank the Center for Global Development issued a report in March 2018 that examined BRI related debt issues and found over 84 instances of China writing off or restructuring bad debt without seizing control of any assets. In addition, China’s Export-Import Bank (CHEXIM) and China Development Bank (CDB) provide most of the BRI loans. As policy banks, the CHEXIM and CDB possess the advantage of only needing to cover their costs instead of making a profit. This advantage allows China to extend concessionary loans for most of its BRI projects, with low interest terms and generous repayment periods. In other words, the basis of “debt-trap diplomacy” disappears if there is no trap of non-concessional loans and profit-seeking rates of interest to begin with. While China is certainly not giving these generous terms out of altruism and the loan terms may change in the future, the accusation that China is currently laying potential debt-traps loses credibility when the evidence is fully examined.

Lim goes on to argue that “not all money is good money,” and that China’s debt-trap diplomacy might lead to potential anti-China backlash, or even regional instability. In particular, he cites the prevalence of racial jokes directed against Chinese people wherever China has made investments, as well as instances of violent attacks on Chinese citizens and Chinese-funded infrastructure. But, it is difficult to find a concrete example of a country that has become destabilized due to economic engagement with China, or failing that, at least a credible attempt to eject China’s presence out of its borders. This argument ignores China’s contributions to the local economies of many BRI recipient countries. Contrary to the oft-repeated myth that Chinese companies along the BRI only hire Chinese workers, a World Bank report from March 2016 surveyed 75 Chinese companies based in Kenya and found that Kenyans represented 78% of full-time employees and 95% of part-time employees. The report goes on to state that Chinese FDI had directly created over 2000 jobs in Kenya.

In terms of foreign aid, after two decades as an aid recipient from the World Bank’s fund for the poorest countries, China was able to “graduate” from foreign aid assistance in 1999. In the years that followed, China was a very reluctant donor to the International Donor Association (IDA), allocating nominal sums while claiming that it remained a poor country and therefore was unable to play the role of donor. However, in the last funding round for IDA in 2016, China emerged as one of the largest donors. This rapid shift appears to be part of a broader strategy that embraces the role of grant-based foreign aid as part of China’s engagement with developing countries. While racial jokes and isolated attacks could indicate unease with an expanding Chinese presence, the reality is that the BRI and China’s foreign aid contributions could actually enhance regional stability through spurring local economic growth and reducing unemployment.

Lim’s article ultimately revolves around identifying the issues behind the BRI, and how Canada should view the BRI through a critical lens. He is correct in a certain sense; China must resolve various outstanding concerns surrounding the BRI, particularly the sustainability of its financing. However, these issues should be addressed on a foundation of mutual respect, instead of subjecting China to the double standard of debt-trap accusations. Malaysia offers a prime example of how even economically weaker countries can negotiate with China regarding its concerns regarding the BRI. When newly elected Malaysian prime minister Mahathir Bin Mohamad visited China in August 2018, he communicated his intention to cancel and possibly renegotiate $20 billion worth of BRI related projects. Nevertheless, he framed the issue not as a critique of the BRI or China in particular, but against unsustainable financing in general. As seen through China’s response of acknowledging Malaysia’s concerns and consenting to further negotiations, Mahathir demonstrated a productive method of engaging with the BRI issues that Lim raised. By communicating concerns from a position of mutual respect, both China and Malaysia protected their own interests without harming their bilateral relations.

By pursuing a similar track, Canada’s endorsement and potential participation in the BRI can help soften the image of the initiative. With Canada’s reputation of being a strong advocate for environmental issues, the engagement of Canadian companies with the BRI could ensure that the projects are subject to proper quality and environmental standards. Thus, Canada can play a positive role in both furthering economic development in emerging economies, as well as enhancing its bilateral relations with China. In this age of increasing uncertainty in the world order, Canada would benefit from diversifying both its trade and political relations, especially with a China whose global role will only become more crucial in the future.

About the author

Leo Luo is a graduate student at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA), majoring in Energy and Environment with a minor in East Asia studies. He also holds a bachelor’s degree from Georgetown’s Edmund Walsh School of Foreign Service.

Notes

[1] Stiglitz, Joseph. Globalization and its Discontents Revisited. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2018

This article was first published by the Canadian International Council. We thank them for their cooperation.