How Chicago Invented the Modern World and Why You Should Experience It

Chicago is many things. Richly cultural, soaring, beautiful, fun, friendly, Futurist, and of great global importance. All things considered, Chicago is the Athens of Modern Times. A visit to this greatest of American cities should be on everyone’s destination list. Canadians have been visiting it since 1673.

How the Chicago Portage became a Metropolis

Through the centre of a great world metropolis flows the Chicago River. “City of the Big Shoulders,” according to the lyrical toponymy of Carl Sandberg. Its main thoroughfare is divided north from south by the DuSable Bridge, named for Jean-Baptiste Pointe DuSable, the city’s first non-Indigenous resident who was born in St. Domingue (Haiti) around 1745 to a French father and a Black African enslaved mother. Some scholars believe his patrimoine was canadien. DuSable settled where French had been spoken generations earlier.

Chicago’s French-Canadian origins

Two bronze bas-relief plaques were installed on the DuSable Bridge in 1925, “by the Illinois Society of Colonial Dames of America under the auspices of the Chicago Historical Society.” The inscription reads: “In honor of Louis Jolliet & Jacques Marquette. The first white men to pass through the Chicago River – September 1673.” Louis Jolliet, born in Québec City, was a cartographer, king’s hydrographer, fur trader, and the first important Canadian-born explorer. Together with Père Jacques Marquette and guided by Indigenous paddlers, these intrepid men mapped waterways all the way from the St. Lawrence to the Chicago portage and the Mississippi. Their names are today commemorated across the continent, including on a pair of streets in Vanier, one of Ottawa’s predominantly-francophone districts.

Marquette and Jolliet were followed by René Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, who, in 1682, undertook an expedition even further south where he claimed the Mississippi River basin for France, naming it La Louisiane. A borough of Montréal is named for him. France eventually ceded the territory around present-day Chicago to the British, who in turn eventually ceded it to the United States following the Revolutionary War.

Jean-Baptiste Pointe DuSable arrived and built a trading post and established a prosperous farm near the mouth of the “Che-cau-gou rivière” in the 1780s, around which grew a small settlement. DuSable sold his land in 1800 to Jean La Lime, a trader from what had by that time become known as Lower Canada. La Lime in turn sold it in 1804 to John Kinzie, a fur trader from Québec City. La Lime, Kinzie, and his business partner William Burnett, also from Québec, were among the first permanent residents. La Lime’s death came at the hands of Kinzie in 1812, making it “Chicago’s first murder,” according to the Chicago Tribune on Friday, November 27, 1942.

DuSable moved to the port of St. Charles, a French-speaking community on the Missouri River also founded by settlers from Lower Canada, where he operated a ferry until his death in 1818. DuSable is today regarded as the founding father of Chicago, although this recognition did not come until 2010 with the naming of the great bridge and the declaration of his homestead’s location as a National Historic Site.

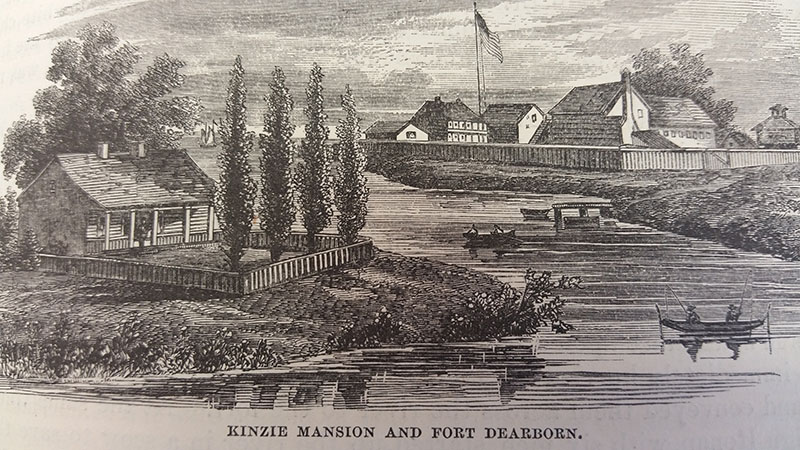

Fort Dearborn and the Establishment of US territory

The Treaty of Greenville was ratified in 1795 by several Indigenous tribes following their defeat in the “Northwest Indian War.” The Western Confederacy ceded large sections of territory south of the Great Lakes to the US government that included “six square miles” located at the Chicago portage. On March 9, 1803, Secretary of War Henry Dearborn instructed Colonel Jean-François Hamtramck of Detroit (born in Montréal) to assign an officer and six men to survey the route to Chicago. A company of troops followed and began construction of a log fort enclosed in a double stockade with two blockhouses. John Kinzie was the de facto civilian leader in the small community who lived on the shore opposite the fort.

The original fort was destroyed near the end of the War of 1812-14. A larger, more formidable replacement was constructed in 1816, only to be de-commissioned by 1837 when it was deeded to the town of Chicago by the federal government. Parts of the fort were demolished to accommodate the widening and straightening of the river in 1855. Almost all of what remained of the fort was destroyed by a fire in 1857. The few remaining auxiliary buildings were consumed by the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

The southern perimeter of Fort Dearborn was located at what is now the intersection of Wacker Drive and South Michigan Avenue near the Chicago Architecture Center. Part of the fort’s outline is marked by plaques and a metal line embedded in the sidewalk and road.

The Great Chicago Fire and the Dawn of Modernity

Chicago was a boom town in the mid-19th century that grew ambitiously; and chaotically, as boom towns do. Seize opportunity, build it fast, deal with the details later. The population in the year of its incorporation, 1833, was approximately 300. By 1871, that number had skyrocketed to 334,270, an extraordinary tally considering that only 25% of US residents at that time lived in urban areas. Chicago transformed from a prairie town into the fourth-largest city in the country. Potential was everywhere. Unfortunately, so was risk.

On October 8, 1871, a fire broke out in a barn. A clumsy bovine, owned by one Mrs. O’Leary, kicked over a lantern that started the blaze, as goes the apocryphal tale. While a cow’s tail end may not have been the cause, the abundance of timber construction, lumber yards, straw, and other assorted fuels fed a fire that killed 250 people, destroyed over 17,000 buildings, and left over 98,000 people homeless in just two days.

Chicago’s status as a major rail and water transportation hub made it essential to the expansion of both the US economy and territory. Much-needed capital poured in from New York to ensure the rebuilding effort was swift. Logistical and legal quagmires, material and labour challenges needed to be overcome. Temporary structures were needed immediately. Nevertheless, the energy inspired by unlimited possibility was so deeply ingrained in the psyche of the city that the fire was seen as an opportunity to create something visionary in which form, function, and beauty coalesced into a new urban ethos. The New York Tribune predicted the “bold, quick spirit…which has made Chicago one of the wonders of the world – which raised a metropolis out of the marsh and sand in forty years…will raise a finer one out of the ashes in ten.” And raise it they did, into the Athens of Modern Times.

The Chicago Architecture Center

Architecture shapes the spaces in which we dwell and interact. High-quality design is uplifting and adds dignity to the human experience. As Philip Johnson, the dean of American architects, put it, “All architecture is shelter, all great architecture is the design of space that contains, cuddles, exalts, or stimulates the persons in that space.” Chicago, it could be argued, has more great architecture than any other city in the Western Hemisphere.

The place to begin, in the city where the streets are a Who’s Who of modern architecture, is The Chicago Architecture Center (CAC), a non-profit cultural organization whose mission is to “inspire people to discover why design matters,” a noble mandate in an age when people focus on screens rather than their surroundings.

The must-see centrepiece of the CAC is the incredible Chicago City Model Experience in the Chicago Gallery. It features over 4,000 building models accompanied by interactive media that tell the history of the city. The CAC is located at 111 E. Wacker Drive on the south shore facing the DuSable Bridge. Across the street you’ll find a blue awning leading down to the river and the ticket booth for the CAC’s “Chicago’s First Lady” river cruise. The 90-minute tour is a must-do that takes visitors up the north and south branches of the river and out into the harbour. Hear the stories behind many of the city’s greatest masterpieces of architectural art from one of the CAC’s 450 expert volunteer docents. Explore the Riverwalk while you’re there.

Where to stay nearby:

The Palmer House, a Hilton Hotel is a palatial and historic hotel located in the very heart of the city, making it a perfect starting point for exploring Millennium Park, The Art Institute of Chicago, and the district known as the Chicago Loop. The opulent central lobby is reminiscent of a French salon and will take your breath away as you ascend the grand staircase. The Palmer House opened just 13 days before the Great Fire. Potter Palmer, its prominent builder and businessman, and his wife, Bertha Honoré, were undeterred by the devastation and decided to rebuild a few blocks away from the original location.

The Palmer House is renowned for many firsts, including electric lighting, a vertical team lift that would become known as an elevator, and the creation of that indulgent dessert called the brownie. It was also the inspiration for architectural innovation. As the fire spread, architect John M. Van Osdel buried his blueprints in a hole in the basement floor and covered them with sand and clay, the principal ingredients of terra cotta. The blueprints survived the fire, leading Van Osdel to believe that he had discovered an effective fireproof material.

Over the years, the Palmer House has witnessed countless historical events and hosted important figures like Charles Dickens, Judy Garland, Ella Fitzgerald, Frank Sinatra, and numerous presidents. Its walls are lined with the portraits of the great performers who have graced its ballroom and its halls. It stands today as the longest continually-operating hotel in the United States. It also stands across the street from the revolutionary and spectacular Sullivan Center, originally known as the Carson, Pirie, Scott and Company Building. Louis Henry Sullivan, mentor to Frank Lloyd Wright and others of the Prairie School, designed it in 1899 as a retail building. As is typical of Chicago, significant works of 20th-century architecture are found on practically every city block. They are identified by plaques and are often designated as National Historic Landmarks.

Where to eat:

The Palmer House, a Hilton Hotel has several excellent options. Lockwood Express is the easiest option for grab-and-go breakfasts and lunches. Lockwood Restaurant and Bar is located just off the spectacular lobby and easily passed my french-fries test. Potter’s Chicago Burger Bar elevates the humble food to a whole new level. Seriously, it’s this simple. Just go, settle into one of its comfy leather sofas, undo your belt buckle, order drinks and stuff your face.

Just around the corner on South Michigan is the Gage Group of buildings, two with no-nonsense facades designed by Holabird & Roche, and the more expressive third by Louis Sullivan. Constructed in the late 1800s, the buildings housed three milliners, including Gage Brothers & Co. founded by David and George Gage who supplied hats to fashionable women at home and aboard. The art installation found in the staircase leading to the lower level features original company advertisements.

Located at number 24 is The Gage, one of the city’s most booked venues offering a lively setting perfect for enjoying its blending of European influence with American style. The restaurant serves refined, rustic fare complemented by an innovative bar. The Gage continues to be both a respected classic and a leader on Chicago’s dining scene. Thanks to The Gage for a splendid meal, its friendly urban atmosphere, excellent service, and its hospitality.

Exploring the Chicago Loop

The Loop is the main business district in downtown Chicago and home to many of the city’s most respected cultural institutions. The Palmer House puts you within an easy walk to many of them, plus more buildings of note and stellar public art. Notice a rational street grid with concealed alleys that keep the garbage out of sight.

The Art Institute of Chicago

When Bertha Honoré Palmer befriended Claude Monet, she began to amass the largest collection of Impressionist art outside of France. Much of it adorned the walls of her venerable hotel, with most of the canvasses eventually being donated to the Art Institute of Chicago, the second-largest art museum in the United States and one of the greatest in the world. Founded in 1879, the Art Institute has a rich and storied history. It has been a centre for artistic excellence, innovation, and education for over a century. The museum’s impressive Beaux-Arts building, located in Grant Park, is an architectural gem in its own right. Visitors are greeted by imposing lions.

The Modern Wing was designed by Renzo Piano and opened in 2009. It’s a successful addition that seamlessly blends modern aesthetics with the grandeur of its historic neighbour. The sleek, glass-encased structure is a testament to innovation and a reflection of the museum’s commitment to showcasing the ever-evolving world of art. Within its walls, visitors can explore an impressive collection of 20th and 21st-century masterpieces. My personal favourite was Architecture and Design, 1900 – present. In the lower level adjacent to McKinlock Court, The Market serves an excellent selection of freshly-made, French-inspired sandwiches, salads, flatbreads, burgers and desserts from Chef Chris Pandel’s La Patinette.

The Art Institute of Chicago is hugely impressive, its collection is awe-inspiring, and its vision of art in our society is vast and deeply meaningful. It requires several days to explore, best done in multiple visits to allow for reflection. It alone is a reason to visit Chicago, for it is nothing less than a temple to the courage of creativity, to turn a phrase by Henri Matisse.

Orchestra Hall

Just across South Michigan Avenue is another temple. Orchestra Hall is home to the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, unquestionably the greatest musical ensemble in the country, the hemisphere, and, according to most critics, the entire world. Imagine, across from one of the greatest art museums on the planet is the home of the world’s greatest orchestra. 30 years ago, I saw Sir Georg Solti conduct one of his final concerts with the CSO. This past January, when they performed at Toronto’s Koerner Hall, Riccardo Muti conducted Beethoven and Mussorgsky. Following the concert, I stood silently in the foyer for God knows how long feeling the peace of a timeless moment; or, as Joseph Campbell wrote, a form of rapture. That’s the kind of experience a truly great city creates.

The Chicago Cultural Center

Just up the avenue in another grand Beaux-Arts building is the Chicago Cultural Center, housed in what was once the city’s first public library. The Center hosts a variety of exhibitions that showcase the works of local, national, and international artists. Whether your interest is painting, sculpture, photography, or multimedia installations, there’s something here to captivate your artistic curiosities. Best of all, entrance to these exhibitions is typically free. Check for programming updates online.

The highlight of the building itself is The Preston Bradley Hall, topped by a magnificent dome originally installed in 1897 by the Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company. It’s the largest of its kind in the world and measures approximately 38 feet (11.5 meters) in diameter, spans more than 1,000 square feet (93 meters), and contains 30,000 pieces of glass in 243 sections, all held together by an ornate cast iron frame. Incidentally, a few blocks to the west is the former Marshall Field’s store, now a Macy’s, on State Street where a 6,000-square-foot (557 meters) mosaic comprised of over one million pieces of glass was installed in 1907 by Louis C. Tiffany, art director of Tiffany & Co.

The Birthplace of the Skyscraper

One of the hallmarks of the 20th century was the sudden upward thrust of cities. Skylines had long been punctuated by the spires and domes of great churches. With the convergence of new materials and technologies like structural steel, elevators, pressurized plumbing, plus the pressure of soaring property values, new heights were achieved for the common person. And so was born the skyscraper in Chicago.

The building that is most often labeled the first skyscraper was the Home Insurance Building erected in 1885. It was designed by William Le Baron and stood at 10 storeys until its demolition in 1931. By 1893, Chicago’s financial district was home to 12 skyscrapers between 16 and 20 storeys in height. An incredible example is the engineering marvel of the 15-storey Reliance Building, whose construction incorporated a number of innovations specific to the Chicago environment. A great way to explore the abundance of important buildings in The Loop is to book a free walking tour with Chicago Greeter, a wonderful program of Choose Chicago.

From 15 storeys to 110, the Willis Tower (formerly the Sears) stood as the tallest building on the planet for 25 years (1,451 feet, 442.3 m). Opened in 1973 and designed by architect Bruce Graham and engineer Fazlur Rahman Khan of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, The Willis is a Modernist masterpiece comprised of an innovative system of square “tubes” bunched into a group of nine. The excellent displays at ground level suggests Khan came up with the idea when he tapped a cigarette pack and a cluster of cylinders formed.

The Skydeck provides the best view of Chicago, and a thrilling feature for the brave of heart. The elevator ride up announces building heights surpassed by Willis. Montréal’s St. Joseph Oratory and the Eiffel Tower, among others. Once up, visitors can step into the Ledge, an enclosed all-glass (including floor) balcony that makes me jittery just thinking about it. Guides will snap your photo with an overhead camera while your feet soar over the sidewalk 103 storeys straight down. Book ahead and plan for a couple of hours to take in all the information.

Foyers and Public Art

Peer into and enter foyers every chance you get to see a style found on Screen Deco movie sets of the 1930s. The monumental Chicago Board of Trade Building has such an interior, polished, gleaming, and adorned with sophisticated metalwork. A little bit of imagination and one can picture Fred Astaire exiting the elevator.

Visible from the south side of the river is the massive Merchandise Mart, the largest privately-owned commercial building in the US and a Chicago icon since the 1930s when it was built by Marshall Field & Co. Its gargantuan facade provides the surface for the largest public art event in the city. ART on THE MART is a must-see evening experience!

Sculptural installations were commissioned from three of the most significant figures in modern art. An untitled Picasso (1967) stands 50 feet (15.2 m) in height in front of the Richard J. Daley Center. It is made from the same COR-TEN steel that clads the building and weighs 162 short tons (147 t). The work is in the Cubist style and was said by Picasso to resemble the head of his Afghan hound.

An incredible pairing of architecture and sculpture positions Alexander Calder’s Flamingo in front of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Kluczynski Federal Building. Calder pioneered the stabile as a sculptural form, with this one standing at 53 feet (16 m). He was undoubtedly one of the greatest and most innovative of American sculptors. Mies was the last director of the Bauhaus, the revolutionary German institute of modernist art, design and architecture founded by Walter Gropius. Following its closure by the Nazis in the 1930s, Mies eventually settled in Chicago where he headed the Illinois Institute of Technology. He is considered one of the fathers of modern architecture and his rational, minimalist designs based on his “less is more” aesthetic are found throughout the world. His tallest is the Toronto-Dominion Centre, headquarters of the TD Bank.

Juan Miró’s Chicago was originally called The Sun, the Moon and One Star. It’s a complex work both in terms of its materials and its representational elements. Steel, wire mesh, concrete, bronze, and ceramic tile form a female figure with a moon at her center and a star above her head. She peers across the street to Picasso’s Afghan, although no relationship should be assigned. While visiting her, look way up at the church spire that soars above The First United Methodist Church of Chicago.

Grant Park and the Waterfront of Lake Michigan

It took great foresight to set aside a huge swath of land by the lake for parks and other public spaces. Grant Park is the result that includes several zones within its 319 acres (129 ha), some of which are reclaimed from the lake.

Millennium Park is an award-winning space for art, music, architecture and landscape design. One of two futuristic features is the Jay Pritzker Pavilion by Canadian-American architect Frank Gehry. It’s easily the most mind-boggling outdoor concert venue you’ll ever see. The other is Anish Kapoor’s Cloud Gate, or “The Bean” as it is more commonly known. It’s a visually puzzling object whose hyper-reflective surface captures and transforms its surroundings. Its setting is currently undergoing a renovation. There’s the interactive Crown Fountain by Jaume Plensa. The Lurie Garden, designed by the team of Gustafson Guthrie Nichol Ltd, Piet Oudolf and Robert Israel, pays homage to Chicago’s transformation from flat marshland to innovative green city, or “Urbs in Horto” (City in a Garden).

Up and around on East Randolphe Street is the Harris Theater, located directly behind the Pritzker Pavilion. It’s a comfortable, casual venue for music and dance, and home to several resident companies, including the Chicago Philharmonic Orchestra. The acoustics are pretty much perfect and the programming is top notch.

There is a beautiful 30-minute walk along the lake that takes you past the massive and iconic Buckingham Fountain to the Museum Campus. The 57-acre (23 ha) park sets three of the city’s most impressive museums: the Adler Planetarium (first in the US), the Shedd Aquarium (where waves crash against its breakwater), and the Field Museum of Natural History. All are impressive beyond belief. The best deal for admission to these and many other venues around town is available at Chicago CityPASS®.

A Sampling of Chicago’s Many Fascinating Neighbourhoods

North Michigan Avenue is known as “The Magnificent Mile,” renown for its shopping. Head north past big department stores, indoor malls, and plenty to keep your purse or wallet open. Look up at the elegant John Hancock Center, today simply 875 North Michigan Avenue. Its 360 CHICAGO Observation Deck is informative and provides a thrilling view in all directions. The entrance fee is included in your Chicago CityPASS®.

In 1964, a group of devotees united to create what would become known as the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. Located a block behind the Water Works Library, the MCA offers four floors of provocative and intriguing exhibits. Check their website for updates, as new work is always being installed for viewing. Marisol is the museum’s excellent restaurant and bar that features innovative flavours by chef Jason Hammel. The space is surrounded by an immersive environment by artist Chris Ofili. Lunch and dinner are served, and it’s the perfect spot for a very enjoyable brunch while you take a break to reflect on what you’ve seen in the galleries.

At the top of The Mile you’ll find the culmination of your shopping experience in the Oak Street District. Known as the Gold Coast, this short street features the highest concentration of luxury brands in town. Be sure and also explore the surrounding area including Rush Street and Walton Street.

Once you’re shopped out, Yardbird on N Wabash Avenue is a James Beard Award-nominated dining experience that is all about modern interpretations of the great American classics. It’s received plenty of praise for its diverse offerings of regional dishes, an excellent selection of bourbons and creative cocktails. As they are proud to say, “We elevate the American bounty with the best of today’s techniques and an obsession with sourcing the absolute finest local ingredients.” Add a few more blocks after dinner to visit Blue Chicago, an intimate, authentic, and friendly venue for the best music the town has to offer. Many thanks to Nik and his team for their hospitality. It was a thrill to see BTS Express with Shirley Johnson, known as the “Sweetheart of the Blues” by the staff at Blue Chicago. Shirley has been gracing the stage there since the 1990s with her heartfelt performances. It’s also a really easy place to strike up a conversation with fellow patrons and makes for an enjoyable nightcap.

A few kilometres out of the core is Frank Lloyd Wright’s Oak Park. Visiting it is nothing less than a pilgrimage for those who value architecture as art. The great master occupied a home and studio in Oak Park between 1889 and 1909. Both are open for tours given by devoted volunteers of the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust. His home was both a prototype and a laboratory. His studio was where he and his associates developed a new, contextually-American philosophy known as the Prairie Style. The surrounding neighbourhood is a living gallery of some of Wright’s most impressive domestic designs.

Fulton Market is a short ride from the downtown. The former warehouse district has been transformed into a hip destination for walking, dining, and entertainment. At its centre is The Fulton Market Kitchen, a unique indoor venue with additional rooftop and outdoor seating.

Multiple menus are offered by different chefs, all wrapped in a fascinating space that has an artful quality to it. Back on the street, and by some luck-luck, we got into Duck Duck Goat, a Chinese-American establishment with an amazing menu that guarantees that it is always jam-packed and humming. The delicious hospitality was much appreciated.

“Itoko” means cousin in Japanese, and refers to its connection to Momotaro, located in the Fulton Market District. Dining at Itoko in Lakeview was like taking a writing test: Transliterate the flavours and textures of one of the most sublime meals you’ve have ever experienced into words. And I mean not just of the Japanese variety, but of any cuisine, anywhere, ever. It was as if Chef Gene Kato discovered a way to transform the greatest works of the Art Institute’s collection into little, perfect culinary masterpieces. Don’t take my feeble word for it. Uber, walk, hire a dog sled, do whatever it takes to get to Itoko. My personal recommendation is to forgo a menu and trust your server to just bring you one rapturously-delicious surprise after the next.

Here’s a sampling. Suke Sake – marinated salmon in toba soy, khombu, dashi, and onion, topped with caviar. Kinmedai – golden eye snapper topped with yuzu kosho. Hokkaido – scallop, uni, and ikura. How about a Yuzu Dropped – broker’s gin, honjozo sake, yuzu, and lime. Dessert? A Berry Kakigori strawberry ice that was a perfect after-meal. Our thanks to Itoko for the hospitality. You should be world famous for what you do to the palate.

For more information, be sure to visit www.choosechicago.com, where you will find even more reasons why Condé Nast Traveler readers voted Chicago the Best Big City in the United States for a historic seventh year in a row.

Photos: Unless credited otherwise, all photos are by Michael Bussière

Before you leave home, ensure you have Probiotics to help fight travel bugs. They are a great way to get out and see a new destination without any hangups.