“In This Place, I Am Here” Grounds You in the Surrounding Landscape

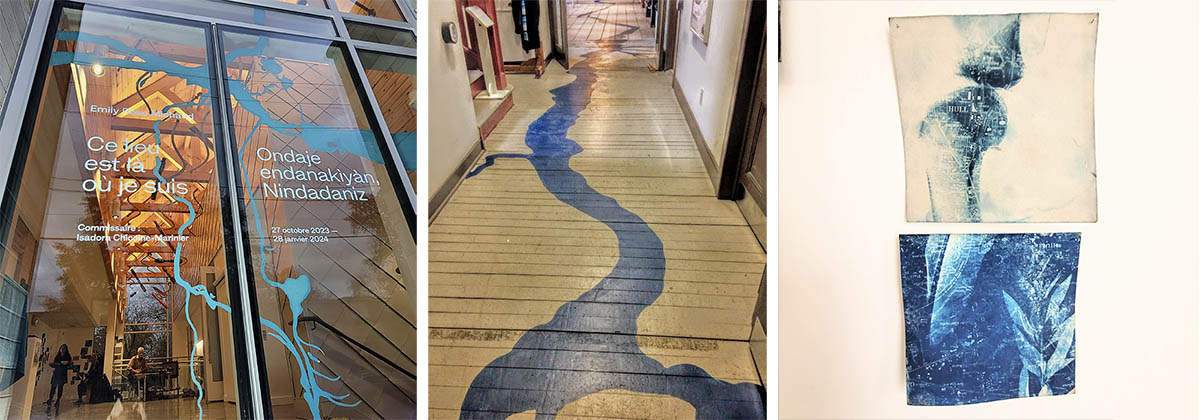

Over the last ten years, artist Emily Rose Michaud has spent a lot of time in the Outaouais region, along the Kichi Sibi (Ottawa) River and its tributaries, compiling a vast body of work on the ecosystem. Her recent exhibition of work features an incredible array of interdisciplinary media, including illuminated sculptural installations, interviews and artworks made with foraged materials from the local landscape. This latest exhibition produced over the last 18 months with Curator Isadora Chicoine-Marinier, is titled 𝐎𝐧𝐝𝐚𝐣𝐞 𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐚𝐧𝐚𝐤ì𝐲à𝐧,

The artwork is a wonderful opportunity for everyone to reconnect with our natural landscape, something that surrounds us and has incredible restorative powers yet is forgotten in the hustle of day-to-day life. It is also a reminder of our shared connection to the land and the importance of safeguarding the precious resources it offers.

Michaud’s artwork is not only based on the Outaouais region; the artwork literally comes from the region. Even the paper used to make a scroll was made by her own hands from different fibres scavenged from the shoreline of local creeks.

The inspiration is drawn directly from the land, but it is the “great river” or Kichissippi in the Algonquin language that leads you into the exhibition. Small blue canvases form the path that brings art and ecology together in the footprint of the Ottawa River basin and its tributaries. The paintings intentionally flow from the door directly across from the entrance to the main exhibit and then to a large window that depicts a painting of the Ottawa River herself. Land and water come together and are celebrated through art.

Inside, your eyes catch the living tapestries on both sides of the wall. Over twelve feet long, they look as though they could be the roof of an ancient shelter. Suspended like a curtain or waterfall and draped over driftwood from the river, the tapestries were made by growing germinated seed upon burlap with pea shoots, wheat grass and buckwheat sprouts, their roots binding through the weave of the textile to create a natural embroidery woven by the life cycle. One of the tapestries was created in July, while the second was completed in September — both are dried and show their age with the faded colour of the grasses. These tapestries showcase the progression of time and how the natural world is affected by change — a shared theme with the rest of the artwork on display. The tapestries appear to defy physics as they gradually meander down towards the ground.

It’s the kind of thoughtful relationship with nature you’ll also find in outdoor design work by Abloom Landscape Contractor, a company offering beautifully crafted decks in Ottawa and other landscaping services.

Below, mirroring the display, is a similar arrangement of thin, translucent porcelain tiles that form the contours of our watershed. Illuminated from underneath and surrounded by sand borrowed from the local shoreline, the piece shines a spotlight on the liminal space between land and water and all the life they feed.

Michaud explains her work as an interrelated triangle of art, education and ecology. “I’m using art broadly to connect people to this place. I also never learnt much about the Indigenous history of this territory as it wasn’t in our textbooks or taught to us.”

This theme of untaught and forgotten history is highlighted in the incredible series of interviews Michaud has digitally woven together, including one with Pauline Decontie of the Kitigan Zibi Reserve, who shares her life story as it pertains to the local landscape. Michaud points out that, although Kitigan Zibi is connected to the National Capital Region by waterways, many settlers, including herself (until her 20s), are largely unaware of its presence. Additional interviews with local teachers, workers, children and long-time residents who share reflections and memories of the human impact on the landscape, as well as what is gone that is missed, have an originality that heightens the experience.

Video footage shot by the artist at site-specific locations in the landscape is also a part of the exhibit. Michaud took footage of the river that shows the beauty and serenity of nature. A large projection screen displays video footage along with an audio soundscape of recordings throughout the seasons. The viewer is reminded how close Ottawa and Gatineau are to nature. Compared to many other cities, it can be found outside our back door.

Make sure to stop and take in the stunning four-piece display of wall tiles created in collaboration with L’atelier de l’Aube (Marie Drolet and Oleksandr Polishchuk). Each represents one of the four seasons. With seven tiles per season depicting plants native to the area and illuminated from behind, the work is beautiful and profound, with meaning on the complexity and interconnectivity of our natural world. A series of writings can be found in a binder in the main lobby that mention the lovely impressionistic/personal descriptions of the various plants depicted.

Michaud’s wonderful exhibition will give you a renewed appreciation for the natural environment that surrounds us, that we, more often than not, take for granted. We have a symbiotic relationship with the great river; mutual respect and understanding are the only paths forward. Michaud’s works will have you looking at the Ottawa River watershed more carefully and with a renewed appreciation.

Make sure to drop into the exhibition 𝐎𝐧𝐝𝐚𝐣𝐞𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐚𝐧𝐚𝐤ì𝐲à𝐧,

For more information, visit: limagier.qc.ca and emilyrosemichaud.com

Find Emily on Instagram at emilyrose.michaud

Header image: Courtesy Emily Rose Michaud