One fish, two fish; red fish, arson.

They’re ugly. They’re bottom feeders. And they’re delicious – especially with a little melted garlic butter.

It is virtually impossible for anyone in Upper Canada or points west to understand how important, lucrative and competitive the lobster industry is in Atlantic Canada.

This results in national news stories about the industry often sounding like they’re talking about some quaint little touristy remnant of a bygone era, rather than a $1billion/year business.

In Nova Scotia, the value of lobsters exported to China alone was in excess of $450m last year. That is $450 in real GDP for every single man, woman and child in the province.

It is an industry that deserves every bit as much respect and solemnity as the oil industry here in Alberta or the auto industry in Ontario.

Unlike those other industries – or even other lucrative fisheries in Atlantic Canada – however, the barrier to entry for lobster is relatively low: ya don’t need big freezers or expensive gear or a boat large enough to travel a long distance.

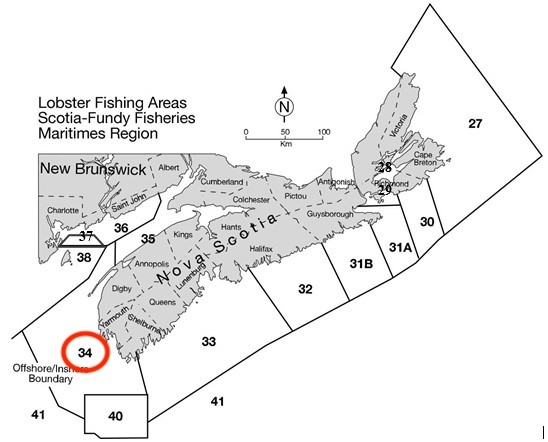

But those licenses are incredibly valuable – they are often passed from one generation to the next and represent a significant transfer of wealth. As the map above shows, the whole coast of NS is divided into a dozen different Lobster Fishing Areas (LFAs). Every license has a trap limit attached to it and each LFA has a total catch based on the number of licenses and traps. The seasons vary from region to region based on water temperature, molting seasons and mating seasons.

Hell, I know guys at home who go out every morning in season with a license, a handful of traps and a small boat with a hoist. Some of them in their seventies! You can’t keep them off the water!

Why? In short: the lobster industry is big money and the established players have an awful lot to protect.

And sadly that’s what the current situation in Southwest Nova Scotia is really about: greed. When people have had ahold of a good thing for a long time they become convinced that it is theirs by right. Think Alberta and the oil industry.

When it comes to fishing in the Maritimes, however, there have been people at it for a lot longer than any “settler” white fisherman – the Mi’kmaq people. But for a long time it wasn’t so clear what their rights were when it came to these lucrative fisheries.

Enter the Marshall Decision.

In 1993 Donald Marshall Jr. – a Mi’kmaq man from the Membertou First Nation – was arrested after selling 210kg of eels for $787.10 and charged with, ostensibly, catching and selling them out of season.

After years of winding through the courts, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled in 1999 that based on friendship treaties from the 1760s, the Mi’kmaq and Maliseet peoples of the east coast had a treaty right to fish to earn a “moderate livelihood”.

Now, it’s important to understand that everyone in political Ottawa was assured by Justice Canada at the time that there was “effectively zero” chance the court would rule against the Crown (i.e., in favour of Marshall). This was, of course, proven to be nonsense, but I’ve always felt that Marshall’s previous run-ins with the law (they were… extensive) influenced that view. He was seen as a trouble-maker by the white establishment, even though he had been the one gravely wronged by the justice system.

Whatever the reason, the government was not at all prepared for the the Marshall Decision and its far-reaching implications.

The first troubles came at Burnt Church First Nation in New Brunswick. From 1999-2002 waves of violence between white (settler) fishermen and Indigenous people ebbed and flowed. Simultaneously similar scenes played out in Indian Brook and Yarmouth, NS.

Tensions were eased via band-aid solutions and the situation had been largely quiet – small flare-ups from time to time but largely peaceful. But no overall solution from government that recognized the Indigenous right to fish and married it with a negotiated system that addressed conservation and seasonal concerns that are regulated for other fishermen.

The two sides have been working together – largely – in an integrated fishery since Marshall. That’s lead to increased capacity among Indigenous fishermen. So without a formal framework between Indigenous fishing communities and DFO, that increased capacity is now looking to make some money.

And that has lead to a new flare up in violence – this time in an incredibly dramatic and dangerous way.

In recent weeks escalating violence by white fishermen in Southwest Nova Scotia (the area included in the circled LFA 34 above) against local Indigenous folks has culminated (so far) in the burning of a lobster pound (the place fishermen bring their catch for sale or storage) in the early hours of October 17th.

The argument of the white, commercial fishermen is largely focused on conservation. Nova Scotia (like Newfoundland) relied heavily on the cod fishery that disappeared in the early 1990s, largely due to overfishing. They couple this with the fact it is molting season for lobster and there is a higher risk of damaging the ugly little critters during harvest.

However, as this BBC article points out, both of those arguments are largely bullshit. The US fishery (based in Maine on the other side of the exact same body of water being fought over in Nova Scotia) harvests molting lobster all the time. They just can’t be exported.

Moreover, the scale of the Indigenous fishery just isn’t big enough to justify any serious concerns when it comes to the size and health of the stocks:

In LFA 34, the regulatory name for the body of water near St Mary’s Bay, where the Indigenous lobster fishery is located, there are 979 lobster licenses, and each license is allowed to carry about 375-400 traps during the season. The Sipekne’katik fishery has issued 11 licenses, with the right to carry 50 traps each.

So, pretty clear, the conservation argument is bullshit. The knee-jerk response to that reality for many from away has been to assert that this is just plain old racism on display.

I’m not convinced. I think racism is a symptom, not the disease itself. It seems to me that the the disease is, in fact, an even simpler, more basic human emotion: greed.

Multiply out the numbers quoted above: the commercial fishermen are dropping over 365,000 traps every day during the season. Let’s say they average one 2lb lobster per trap, per day. And let’s say the price on the wharf is $8/lb. That’s $5.8m per day to the fishermen during the season. And the season in LFA 34 runs for six months.

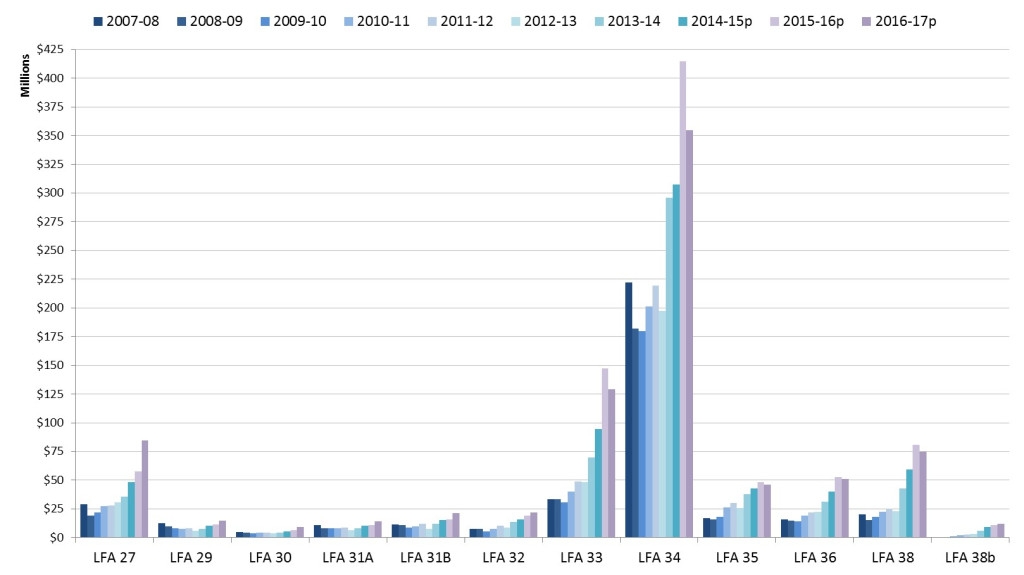

In fact, as you can see from the chart above, LFA 34 is – by far – the single most lucrative area for catching lobster in Atlantic Canada. By far. As the chart above show, in recent years the landed lobster catch in LFA 34 has been valued between $300-500m/year. The next closest zone – LFA 32 (around Halifax) – is less than half that.

So yes, undoubtedly the white, commercial fisherman have been saying and doing racist things. Undeniably. But the motivation is necessarily the protection of this resource they see as theirs: and not protection from environmental or conservation-related threats, but protection from their industry being shared with anyone else.

But it isn’t just the commercial fishermen who are using conservation as their fig leaf. A series of successive federal governments of both political stripes have been perfectly content to do so as well. And while it is no more believable coming from Ottawa, its is frankly all the more shameful.

Just as much as any pipeline, the lobster fishery in LFA 34 is where the rubber of economic reconciliation meets the road. And the indecision and inaction to date cripples any notion of the federal government as an honest broker here.

This is especially the case with the RCMP who are contracted to provide local policing – is pretty hard to swallow. Watching the Mounties stand around while Indigenous property is destroyed only adds to that credibility gap.

(And it is worth remembering that the RCMP in Nova Scotia do not exactly have a surplus of good faith or credit with the public right now…)

So what should be done?

First and foremost, law and order must be restored. I don’t care if the Canadian Forces have to be brought in or a whole new batch of RCMP direct from the depot, faith has been broken and the federal government has an obligation to step in and restore the peace while protecting the Mi’kmaq fishermen while they exercise their clear treaty rights. Nothing else will matter until that happens.

The behaviour of many of the white, commercial fisherman is abhorrent and absolutely beyond the pale. Their racist actions and language are utterly unacceptable and should be roundly condemned by everyone in NS and elsewhere. This is fundamentally not a question of “good people on both sides” – they are in the wrong and need to stop.

But a close second needs to be a genuine process for working with local Indigenous communities to create a process that recognizes and response genuine conservation concerns, seasonality, etc. Those Indigenous communities will then be in a position to issues licenses (as the Sipekne’katik have done, btw) that DFO and the commercial industry must respect.

The new Fisheries Act passed last year puts a direct emphasis on traditional Indigenous knowledge when it comes ministerial decision-making. This should be a first test and case-in-point.

This should have all happened twenty years ago. The fucking about on all sides is what has lead to the violence we are now seeing in Southwest Nova Scotia and the greed of the commercial fishermen is oil being poured on that (literal) fire.

Only the Government of Canada can step in and fix this problem in a way that respects the legitimate rights and interests of all sides. That it is not done so to date is not just a shame, it should make any and all discussion of reconciliation with First Nations extremely suspect.

Jamie Carroll is a former National Director of the Liberal Party of Canada and has pulled the occasional lobster pot in and around LFA 31 and 27.