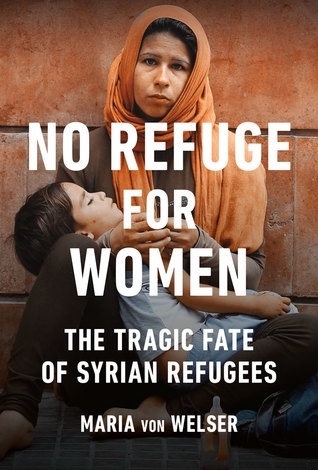

Restigouche: The Long Run of the Wild River

BY: Lee, Philip (2020),

PUBLISHER: Goose Lane Editions

PAGES: 272

ISBN: 9781773100883

Reviewed by David B. Brooks

Philip Lee has given us a fine book about the life of an important, ancient, and northerly flowing and still partially “wild river” in New Brunswick. However, it does not deserve all the loving kudos that one finds on its back cover, and I say that as someone who shares most of the author’s conservationist and democratic political perspectives, as well as his respect for the Mi’gmaq people who were the its original inhabitants. I also say it as a lifelong canoeist who has travelled many of the wild rivers in Canada, though not, regrettably, the Restigouche.

First, my one complaint: How can anyone write or publish a book about a river without a map to show its full course? The geography may be second nature to someone living in New Brunswick, but it isn’t to the rest of the readers. Sketch maps of several reaches are only second best.

To shift to the positive, I applaud the structure of the book with descriptions of travel interspersed with history of the river and of both its traditional and its more recent industrial and recreational uses, and with emphasis on the Indigenous people whose traditional knowledge and rights have been so often ignored. I also applaud the way the political dominance that the timber industry came to exert in New Brunswick is so frankly described along with their building of near-palatial recreational villas along the river.

In short, the book is a great combination of delightful semi-wilderness river trips on the Restigouche, and a highly political book about the need to protect and restore the river while maintaining some of the economic aspects that the government of New Brunswick needs in order to survive the next election. Accomplishing that combination of goals will be no easier than standing in a canoe while moving in fast water.

And to end my review, I must salute the salmon whose presence and whose fidelity in returning each spring meant so much to everyone who lived nearby and drew substance from them—or simply pleasure from hook and release—year after year after year no matter how badly humankind treated the river that was their ecosystem.