The Métis — Ignored No Longer

There are emerging signs that the Federal Government is finaly recognizing Métis land claims.

The people of the Métis Nation number 350,000 who are spread across much of Canada and some of the northwestern U.S.A.

The definition of the members of the Métis Nation put forward by the Métis National Council is: those who self-identify as Métis, are distinct from other Aboriginal peoples, are of historic Métis ancestry and who are accepted by the Métis Nation.

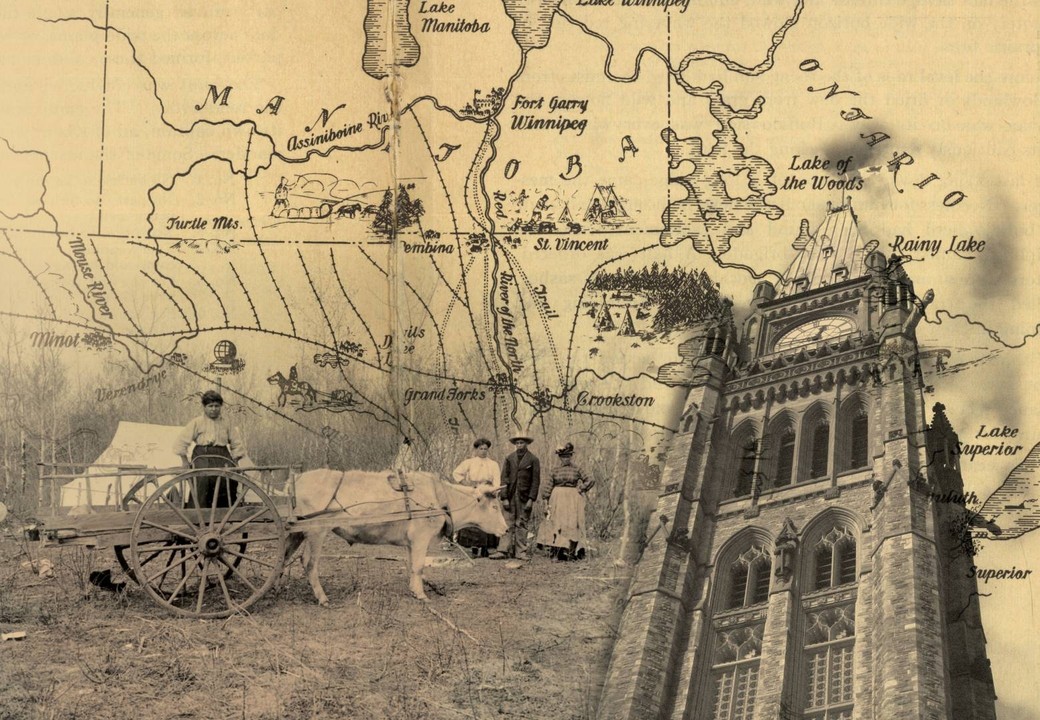

This unique identity, unlike any other in the world, began in the 1700s, when European fur traders and voyageurs, mostly French, met and married the indigenous women of North America, often Cree or Ojibwe, and their children and descendants through the generations were raised in a fusion of colonial and aboriginal cultures.

Consequently, written history, oral history, and legal records have enabled the Métis Nation to document their treatment by governments, whether French, British, Canadian, territorial or provincial, and that treatment has been conclusively lacking in fairness, honesty, or honour.

One of the paper trails which enables Métis to trace their roots includes the infamous scrip, a piece of paper given to Métis children of the Red River Settlement as a way of giving those 7,000 children a “head start” since they were already living in a place which the government was determined to open to settlement.

Why additional settlement was encouraged seems impossible to comprehend now. If they already had 12,000 settlers, of which 10,000 were Métis, why was there any need to bring in more? Of course the settlers coming in from Ontario were English and Protestant, at a time when systemic discrimination against French, Catholics, Aboriginal North Americans and “half-breeds” (as Métis were then called) was an established and condoned practice of the British Empire and the Government of Canada.

When surveyors arrived at Red River in 1869 Métis including Louis Riel turned them back. The leaders were neither stupid nor naïve and they were well aware (as later actions on all sides showed) that the transfer of the Red River portion of Rupert’s Land by the British Crown to Canada was done without giving any thought to the thousands of people already there. Their flourishing home and vibrant culture would be swept aside as if it had never been if the Crown had their way.

Thus was born the Red River Rebellion in which Riel’s provisional government was finally able to win negotiations with the Crown. Those negotiations resulted in 1.4 million acres being set aside for the Métis children and their descendants in exchange for the annexation of Manitoba. The Manitoba Métis, as negotiating partners, agreed to lay down arms and allow the province to be formed and annexed to Canada. This foundational deal, or compact, led to the westward expansion which ultimately included the western provinces and many riches for the country.

“These compacts go to the heart and soul of Canada,” say Jean Teillet and Jason Madden of the law firm Pape Salter Teillet in a summary. “Manitoba became part of Canada on July 15, 1870. The Manitoba Act was made part of the Constitution of Canada in 1871.”

Numerous delays and errors defeated the purpose of the agreement, however. Meanwhile, settlers and speculators were already moving in. Strife arose between the new people from Ontario claiming land and the existing inhabitants, resulting in many Métis being effectively driven from their homes by English vigilantes. In the end many Métis moved outside the province which they had helped found. The situation was aggravated by needed migration for hunting or harvesting purposes in different seasons—a semi-nomadic lifestyle— making dismissal of land claims easier. Practically no children ever received land, but Canada received untold riches by the opening of the West.

The diaspora of the Métis, combined with the limited opportunities for education of that time and place—especially lack of literacy—meant territorial, provincial and federal governments could ignore the displaced and dispersed Métis descendants.

Over the centuries Aboriginal rights were barely recognized in Canada, and only for First Nations and Inuit peoples. It was not until 1970 that a high court stated that the “doctrine of discovery” was incorrect, as the people who were here first had the rights to interest in the lands, forcing a change in government policy.

But the Métis were ignored completely, or brushed off with excuses. Sometimes it was convenient for governments to claim they had been European settlers who had individual property rights dealt with through scrip, extinguishing any collective rights including traditional harvesting/hunting rights. Other times government argued they were nomadic and therefore had no specific territory to lay claim to, something generally used to establish a First Nations or Inuit land claim.

In fact the Métis were not recognized as a unique group with specific rights until The Constitution Act of 1982, and there were no efforts made towards reconciliation. It was not until 2003 that Supreme Court heard the Powley case, regarding hunting in Ontario, and unanimously agreed that Métis shared Aboriginal rights.

Even worse, it was not until a Supreme Court decision issued in 2013, over 140 years after Canada gained Manitoba, that Canada was at last forced to acknowledge that the government of John A. Macdonald, although it had given the original scrip to individuals, had not acted with the Honour of the Crown, and that Canada would now have to treat the outstanding land claim as collective.

So far Canada has not undertaken negotiations with the Manitoba Métis Federation (MMF), who brought the case to court, but the MMF is building capacity for that reconciliation, which will come eventually.

“The Métis have been around since the 1700s,” says Al Benoit, MMF advisor. “We’re still here, but governments come and go.” Currently Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau and Opposition Leader Tom Mulcair have both stated they will act on the Court’s decision. The government in power has not. “Eventually there will be sufficient political pressure,” Benoit says.

Lawyer Jason Madden agrees. “The trajectory of Métis’ rights is a given,” he says. “It is government’s nature to stall, delay and obstruct, but the way forward is clear. The idea of recognizing only two of three groups with Aboriginal ancestry is a non-starter. The reality is the time has come to finally negotiate with the Métis.”

Regarding what can be reasonably expected the land, of course, is now almost all in private ownership, so the claim may end up being a broad package, presumably including some Crown land, some funds which would likely go into a trust, and some benefits.

“We are forward-looking,” says Benoit. “The original scrip was to benefit the children of Red River. Those children were cheated of their inheritance. So a trust would provide long-range benefits for our children, by making investments in areas like education, funds for first-time homebuyers or start-up grants for young entrepreneurs.”

Not all Métis have a share in the claim— only those who descended from the Red River Settlement, although other groups may have other claims. Red River had the greatest concentration of Métis people at the time, but many other small Métis communities were scattered across the north and west. Some of those groups are working on their own reconciliation with provincial governments.

Changes to the way the Métis have been viewed (or not) have been incremental over time. Section 35 of the Constitution Act states that Métis citizens’ settlements are also known as local communities, and that communities, traditional territories, and common culture are what makes up the Métis Nation. A community is made up of people bound together by culture, history, and social and kinship relationships. In this the legal definition is similar to that used by the Métis National Council, so it seems the two nations are finally drawing together in their understanding.

Recognition of the Métis as a distinct nation with reconciliation between the Canadian government and the Métis still has a long way to go, but the path is becoming clear. In his report just released this April, Ministerial Special Representative Douglas R. Eyford said, “Canada must do more in its relationship with the Métis to ensure their section 35 rights are appropriately recognized and can be meaningfully exercised. As the Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples observed in 2013, ‘reconciliation (with Métis groups) is necessary in order to provide a solid foundation for present and future generations of Métis in Canada.’…Canada should develop a reconciliation process to support the exercise of Métis section 35 rights and to reconcile their interests.”

The Métis are a vital, important part of Canada’s citizenry who have been unfairly treated.

At last the time has come to set that right.