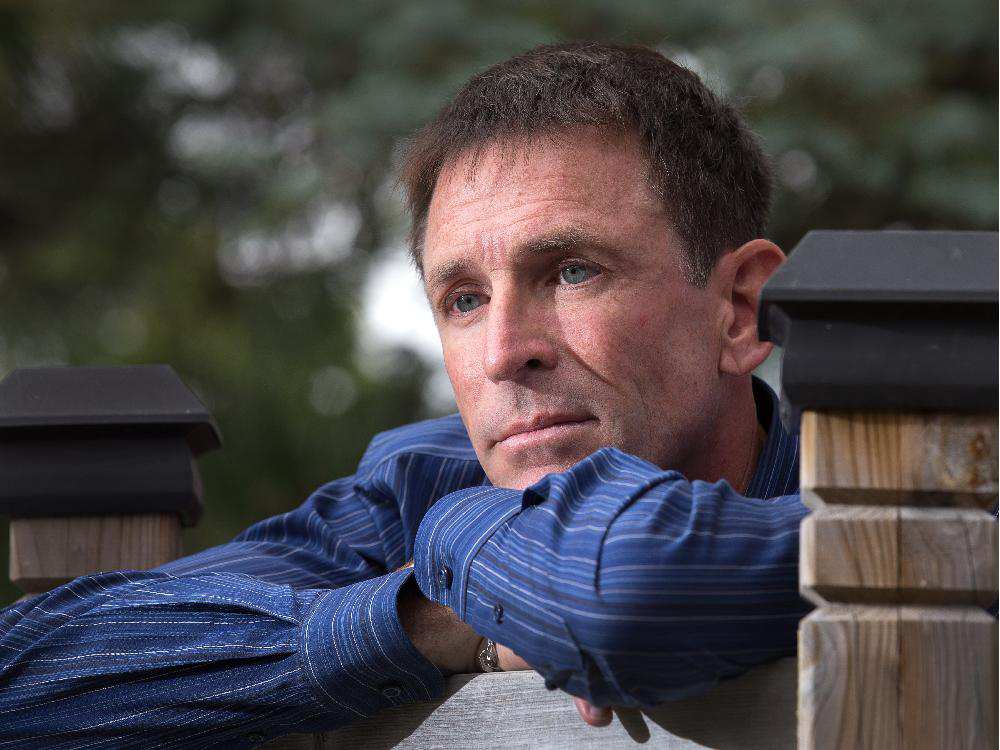

The Other Side of Reason: An OC Transpo crash survivor’s struggle with PTSD

Now, my steps are less assured, almost hesitant.

I think about my family farewells, hugs and kisses — did I remember to say I love you?

With every step, a painful memory of what was in time a bright autumn morning.

–Bus Stop 4608 (David Gibson)

These are the words of David Gibson, one of the survivors of OC Transpo Route 76 that collided with Via Rail Train 51 on September 18, 2013. Though there would be internal struggles to come, hidden scars yet to surface, David was still standing, one of the fortunate ones able to walk away from the crash. The accident, which completely tore off the front of the bus, tragically claimed the lives of six, including the driver.

Though it was over three years ago, Gibson still recalls the moment vividly, the smoke, the debris and the screams. Outside her saw bodies or, in some cases, only pieces of people as first responders, those he considers heroes, started to arrive to help the injured. As he was escorted off the bus, he remembers seeing a pair of black shorts scattered among the wreckage. He never learned who they belonged to.

“It’s weird what you remember, but I do remember walking down Woodroffe and, that all of a sudden came this lady running toward us out of breath – a Globe & Mail Reporter, who just stopped to ask if we were on the bus and what it was like,” Gibson tells Ottawa Life. “ I remember I just looked at her, and turned away to continue walking home. It was like that – a media frenzy.”

In many ways, Gibson is still walking down that road away from the wreckage. An investigation into the accident would take years with the Transportation Safety Board of Canada only producing a full report in December of 2015. During the whirlwind that followed those who survived, people like David Gibson, tried to continue on with their lives.

Gibson returned to work as the Executive Director for the Sandy Hill Community Health Centre and back into being the father of four boys. His family life was always hectic, he says, with having to jump between school and sports with the kids but after the crash it was a welcome distraction from being left alone with his thoughts. The crash was never far from his mind. He started experiencing nightmares early on. He kept reliving it over and over, a macabre mental merry-go-round where, in his dream, he kept trying to change the outcome. He always failed.

“The nightmares compounded my feelings of helplessness over what had happened to me, but they also made it so I was a prisoner to my mind. I couldn’t escape it even in sleep. I got to the point that I was always afraid to sleep. I’d sit up all night until I couldn’t stay awake, then finally fall asleep only to be woken up too soon due to a really bad nightmare. I slipped into a state of constant exhaustion.”

Getting out of bed most mornings became a struggle. A numbness encased him in a strangle hold that wouldn’t let go no matter how he tried to shake it. Every day life tasks now seemed like mountains and he found himself always to be on the edge. Three years later, multiple therapy sessions and medication find Gibson still often feeling lost, helpless and out of control. Those who try to live with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder know these feelings all too well.

Though he fells blessed for the support of his family, friends, colleagues and doctors, Gibson took the important steps to self-heal by writing about it. His book, The Other Side of Reason: A Journal on PTSD, began as a way to relate to his loved ones and to externalize the internal.

“Soon it became very apparent that my story was only one among other silent stories of people living with trauma or PTSD. I quickly realized that tragedy can show us our ties to others and strip us of our differences. Thus the importance of writing this as a book became even more apparent to me – to break the silence that shrouds trauma and release it to the public as a way of confronting real mental health issues in our community.”

Writing became therapy. It can be felt in Gibson’s words. His battle became poetry and the poetry became a place of safety he could retreat to. There was a solace in creativity that rose above the bliss any pill could provide. In the poems he could speak truth. There his words didn’t become angry or difficult to express. His poems became his voice.

“The journal allowed this silence to be expressed. (It) became critical to my path to recovery and expression beyond myself and to others.”

I have become unpredictable to them.

I have become that someone else I don’t want to know.

–The Ripple Effect

“My experience suggests that the silence that surrounds PTSD is in part a mechanism to hide the pain, fear, guilt and shame you feel from being a survivor,” sys Gibson. “Who wants to be around a David ‘downer’ all the time? So you find ways to hide what you are and who you are with anything that works.”

go; I am not the person who is

standing before you, I am the silent

one inside.

Because of this, The Other Side of Reason is a one of those rare books that moves beyond literary escapism and instills within its reader a sense of hope, an assurance that there are ways to move through tragedy, that there is a light somewhere if you are willing to walk towards it. In our hardest struggles, life may feel meaningless, difficult and painful but it is, after all, still life.

“For me, finding the meaning in life has become central to becoming complete again," says Gibson. "I feel encouraged that I am able to share some of my insights that I have learned over the past three years. The most rewarding aspect to writing this book became the most self-evident – where there is hope there will always be a future”

Proceeds will benefit two scholarships set-up in the names of two Carleton university students were killed in the crash.