Why the Canada-China relationship doesn’t have to get lost in translation

Op-ed by Chis Pereira

Smog, wildfires, and intermittent oppressive heat are upon us, leaving us praying for rain and better days ahead without much relief in the forecast.

And with the next federal election just around the corner, we are likewise unlikely to experience much relief from the oppressive and increasingly unprincipled political environment in which Canada now finds itself. Among the issues that will take centre stage during the coming election is the pressing question: What to do with China? Human rights will certainly feature prominently. There are many complex and intricate strategies continually being proposed on how to “deal with” or “contain” China – but have we tried, like, actually talking to them?

As someone who speaks Chinese with over 15 years of experience in China and Hong Kong, I am increasingly perplexed by the disconnect in communication between East and West. China, for the past several decades increasingly respected for its modest, tactful, and often savvy diplomacy, is suddenly finding it difficult to effectively express its desire for equal treatment and respect on the world stage. By every measure, the traditional Chinese cultural ethos of being modest yet assertive (“hanxu”) is sorely lacking in its recent diplomatic communiques.

And Canada, the self-proclaimed role model for cross-cultural understanding, has had a disastrous track record of failures in recent years, having since 2018 utterly failed to communicate effectively with one of the largest and most powerful countries in the world, clearly achieving nothing except the exact opposite of what is good for Canadian interests abroad. Ironically for Canada, the supposed bastion of multicultural understanding and inclusion, with its nearly two million residents of Chinese origin, the most pressing issues with China (including freeing the two Michaels) could be addressed most effectively through better cross-cultural communication, and less name-calling and race baiting.

But behind all the animosity and failed communication, where is the enormous anti-China sentiment in the West coming from? If you ask me, we in the West don’t like China these days because China is increasingly assertive, increasingly capitalist, increasingly efficient, and increasingly better than us at many things. On the other hand, China increasingly views the West as a backwater socialist dystopia (ironic, no?). Neither of these views is entirely correct, and yet the discussion in both countries continues to cement such public opinion on both sides.

While China’s PR and communication strategy certainly needs drastic changes, and while there are serious issues to discuss regarding human rights, nonetheless China is quite rightly demanding to be treated as an equal in discussions rather than acquiescing when the United States pushes for China to remain a Third World country doomed to be forever the low-end manufacturer of dollar-store goods for the so-called First World. No country and no person in the world should be treated in such a colonial way, and this basic respect (without conceding any ground on human rights) should form the foundation of a new policy framework toward China.

Without a doubt, there are disturbing issues that must be resolved immediately with China, including getting the two Michaels home to Canada – but these issues can be resolved in only one of two ways – effective communication and negotiation with an eye to long-term prosperity, or short-sighted and emotion-filled escalation toward cold/hot wars that could quite literally kill us all.

With those risks in mind, with the exception of segments of the mainstream media and Twittersphere whose sad livelihoods depend on the toxic headlines made possible by official press releases copy-and-pasted from government departments and questionably funded think-tanks, no one in their right mind in Canada is pushing for a new “Cold War” with China. In fact, on the ground, trade between Canada and China increased significantly last year, despite everything.

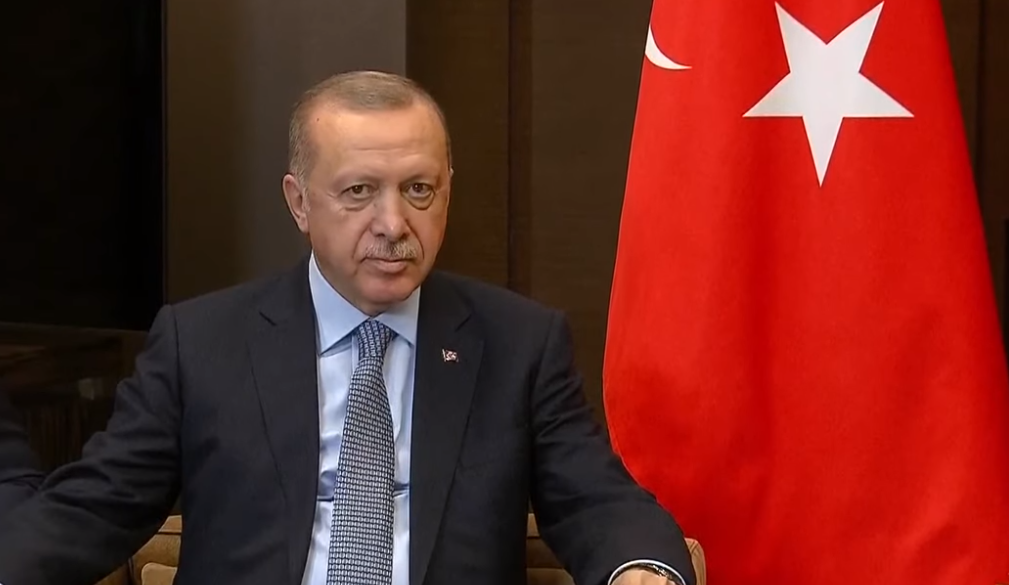

Clearly, there are also myriad pressures from the United States and related interest groups muddying the waters of dialogue, mostly with the goal of suppressing economic competition from Asia, but this is nothing new. Canada has always needed to deal tactfully with superpowers whose values differ from our own – whether it be the United Kingdom, the United States, Russia, Japan, or China.

Canada needs to jump back into the game, figure out how to compete, to do better, and to configure its rules and regulations in such a way that it does not matter what country you’re from – the rules apply equally to everyone here in Canada, whether you’re from communist Vietnam (yes, they are ruled by “communists” as well), Scotland, Cuba (oops, another communist country we have relations with), China, Fiji, Canada’s own First Nations groups (whose traditional communities are also generally not democratically governed), or the United States.

As the election approaches, perhaps we might hope for some whiff of a breeze, some hint of rain, some inkling of relief from the pressure and negativity of the past two years of Canada-China relations. There certainly is a yearning for strong leadership, vision, and a little boldness in Canada’s political scene. And yet a cursory survey of the political landscape leaves one sorely wanting for a leader with vision or even the guts to say something – anything – of substance that is relevant and helpful to the issues we face as a global community.

Failure to effectively communicate between cultures will ultimately end badly for us all, especially in a multicultural society such as our own. We all need to better live our Canadian values, engage in a way that promotes and protects those values, and ultimately makes the world a little better in the process. But strange weather these days, eh?

Chis Pereira (chris@ecoinst.ca) previously worked for Huawei Technologies in Shenzhen, and most recently served as senior director of public affairs at Huawei Canada. Fluent in Mandarin, he serves as president of Canadian Ecosystem Institute.

Republished from BIV.com