Wings Of History

The fragile biplane rotates in a slow circle above the visitors who wander through the Canadian Aviation Museum in Ottawa. Stephen Quick, the associate director general, smiles as he looks up at the structure made of balloon cloth, wood, and steel tubing.

“It all started here.”

Shadows from The Silver Dart’s cloth wings sweep over Quick as he gestures to the airplane.

“This is where it all started in Canada”

The Silver Dart was the first airplane to take flight in Canada. A young engineer named J.A.D. McCurdy flew the aircraft across the frozen Bras d’Or lake in Baddeck, Nova Scotia, on February 23 1909. One hundred years later a replica of the aircraft serves as an introduction to the Canadian Aviation Museum’s Centennial of Flight project.

The project’s goal is to raise awareness of all that aviation has contributed to our country since McCurdy’s short flight a century ago. Today, flight provides Canada with a transportation network, an industry and an air force. The museum is in collaboration with 17 other organizations across Canada, such as Nav Canada, the Air Force Association of Canada and Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame. Each has created events and programs to commemorate the centennial. Quick says that the museum added some new exhibits in order to give context and attract a wider audience.

Four new interactive galleries are spread out between the aircrafts. Each gallery represents an era: Getting into the Air (1902-1918), Tying the Country Together (1919-1938), Industry and War (1939-1945) and Shrinking the World (1946-Present). Artifacts like gramophones, cars, and motorcycles are scattered across the floor to show what was happening on the ground while planes flew overhead. In one corner, children can dress up in pilot goggles and helmets.

Quick strolls beneath the nose of the Bellanca CH-300 Pacemaker as he explains that bush planes opened up all of northern Canada and connected the country.

“We’re a small population set apart by huge distances,” Quick says.

The Pacemakers were used mainly for aerial photography in the 1920s and 30s.

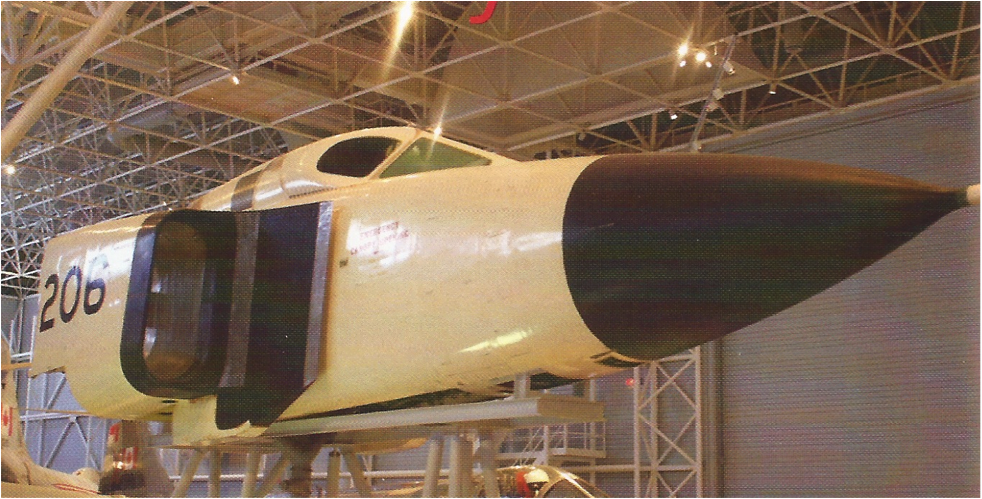

The walk from one end of the museum to the other shows just how far aviation has advanced in the past hundred years. At the front sit airplanes made from wood and that traveled at 70 km/h; at the back are sleek jets that break Mach 2. The nose of the Avro Canada CF-Manufactured in 1957 in Mahon, Ontario and first tested in 1958, the sleek and elegant Avro Arrow was a technical masterpiece at the forefront of aviation engineering during its time. The delta-winged interceptor aircraft held the promise of Mach 2 speeds and could exceed altitudes of 50,000 feet. Designed at the height of the cold war, the Avro Arrow was meant to be used by the Royal Canadian Air Force to intercept and destroy Soviet Union bomber planes. However, in 1959 the Canadian government decided the threat from the east had diminished and ordered all completed Avro Arrows to be destroyed. Only five ever made it off the ground, and then only ever during test flights.

The nose of one of the Avro Arrows is all that remains of this legacy in Canada’s flight history. The Institute of Aviation Medicine donated it to the Canadian Aviation Museum in 1965.

Quick says that the airplanes are just one part of Canada’s flight history.

“It’s the stories of the people who flew them that are really important.”

Don Gregory was a pilot for half a century and has stories to share. He stands a little straighter as he points to the first and last plane he ever flew. It’s a bright yellow North American Harvard II, and in 1953 Gregory was training for the Air Force the first time he ever got behind the controls. After fifty years of piloting all types of makes and models, it was that familiar bright yellow plane that Gregory flew for his final flight in Hamilton in 2003.

Today Gregory volunteers at the Canadian Aviation Museum, where he imparts his wisdom, experience and love of flight to visitors.

“I can tell you stories you can’t read on the story boards,” Gregory said.

He chuckles as he reveals that the North American Harvard II can do aerobatics – rolls and loops in the sky – but doesn’t say whether he knows this from personal experience. Gregory gestures with his hands as he talks about the importance of flight in Canada. He points out that Canada manufactured its own mail planes and war planes, and that today Canada is the third largest producer of civil aircraft in the world.

“More people should learn about this part of our Canadian history,” Gregory said.

A series of events hosted by the museum provide learning opportunities all summer. Biplane and helicopter rides are offered starting in May. Artflight, an aviation-themed art competition, begins May 14. This year’s theme is Miles, Milestones, and Moments. The museum will also host a classic air rally on August 29 and 30. The Centennial of Flight exhibition is ongoing.

The museum has also published a Children’s book called “The Fantastic Flight of the Silver Dart” which can be purchased in the gift shop or online.

Quick, a self-described “propeller head,” says he is happy to host a commemoration of Canada’s history of flight_ To Quick, airplanes are pieces of art whose beauty lies in both their manufacturing and their function.

“There’s the romance of the flight,” Quick said.

“Being in another element – the air – is amazing.”

By: Natalie Stechyson