“A House Divided Against Itself”: The 2012 Republican Race for the White House

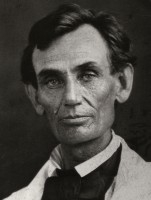

In the summer of 1858, two years before he would become the first Republican President of the United States of America, Abraham Lincoln uttered a phrase that still applies when he accepted his party’s nomination as the Republican U.S. Senate candidate for the state of Illinois. At the lectern in the Springfield statehouse, referring to political issues of the day, Lincoln stated that, “a house divided against itself cannot stand.” Today, 154 years later, that single sentence could be used to sum up the results of Super Tuesday 2012 and, on a larger scale, the Republican Party’s continuing difficulty in finding, and then nominating, a candidate supported by all the different demographics within the GOP who could challenge Democratic President Barack Obama in this November’s presidential election.

Super Tuesday, the first Tuesday in March of a presidential election year, is traditionally seen as both a confidence builder and a field narrower. Essentially, it is a day when ten different states hold their primary elections or caucuses to try to determine the candidate who best represents their interests in the contest to win the Republican Party presidential nomination. However, the key word here is try. For a Republican candidate, the first real test in the road to the White House hinges on the ability to gather the 1,144 delegates needed to secure the party’s nomination. Super Tuesday is seen as crucial in this race since there is a total of 419 delegates up for grabs in the ten states on that one day. Furthermore, the demographic cross-section of the states voting on Super Tuesday is perceived as a microcosm for the voting habits of many of the other states in the union.

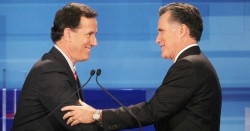

Nevertheless, the most important state from a candidate’s point of view is Ohio. Ohio is seen as having one of the closest and most representational demographic samples of the entire country. As the saying goes, to win the presidency, you must win in Ohio. While former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney did indeed win Ohio — albeit only by an extremely small margin — alongside Massachusetts, Vermont, Virginia, Alaska and Idaho, Romney is still facing stiff opposition from former Pennsylvania Senator Rick Santorum, a more polarizing candidate, who won three states on Super Tuesday: North Dakota, Tennessee and Oklahoma.

Although Romney remains the frontrunner for the party’s nomination, many inside and outside the Republican Party continue to question his legitimacy as a conservative. The former Massachusetts governor is often labeled as being too moderate. Despite the fact that Romney has won the greatest number of delegates to date and consistently polls better than any of the other Republican contenders against President Obama, he continues to frustrate the more conservative wing of the Republican Party, including the Tea Party movement: a sure sign that the field will not be narrowed anytime soon.

Instead, Mitt Romney, Rick Santorum, Newt Gingrich and Ron Paul — the four remaining candidates — will all likely stay in the race, continue to trade punches and to air their dirty laundry through negative attack advertisements perhaps until the Republican Convention in August of this year. On the Democratic side, such a prolonged nomination process occurred just four years ago when Hilary Clinton and Barack Obama fought each other well beyond Super Tuesday until Obama eventually won the nomination. Many would argue that the lengthy nomination process in 2008 strengthened Obama as a candidate for the general election. The jury is still out on whether the ongoing Republican races will have the same effect on Mitt Romney if he does eventually win the Republican Party’s nomination.

The reason why this is less certain for Romney is that, for the time being, the Republican Party appears to be a “house divided against itself.” Romney is having trouble winning over the more conservative voters as well as many blue-collar voters which is translating into hard-won primaries and caucuses in states outside of the Eastern seaboard. At the other end of the spectrum, Rick Santorum is running strong in the blue-collar and more conservative Mid Western states. The victory of Tea Party favorite, Georgia native and former Speaker of the House of Representatives Newt Gingrich, seems to be limited to the Southern states.

Unless one of these candidates is able to obtain the required 1,144 delegates needed to secure the nomination before the Republican convention in August, there is a possibility that no nominee will have been elected, thus splitting the Republican Party along clear geographic and demographic lines, with no one candidate being able to appeal to all factions. This is a dream come true for President Obama and the Democratic Party. It would result in a brokered convention in which delegates would need to be divvied up or swapped and political horse-trading would be required so that one candidate would have enough delegates to win the nomination. The other wildcard in such a scenario would be to parachute in another candidate capable of uniting the Republican Party in a way that none of the four candidates have, up until now, been able to do. In either case, a brokered convention would reduce the prospects that a Republican candidate could defeat the incumbent president.

And so, the Republican Party’s nomination process continues: primary after primary and caucus after caucus. Unless the Republican Party’s coalition of voters coalesces around one of the four candidates in the race, Abraham Lincoln’s prophetic warning could come to describe his own political party, costing his party the White House.