First Canadian Bank’s Storied Links to the Nation

Our chartered banks are now the bedrock of our economy.

Until the 1930s, Canada’s first bank — the Bank of Montreal — enjoyed a pre-eminent position in the economic and political life of Canada, and has remained a pioneer and leader in its financial affairs ever since.

A lavish photo and fact filled book, A Vision Greater than Ourselves by Lawrence Mussio, has been published in honour of the bank’s 200th anniversary this year. It is full of surprising evidence of how closely this institution has been linked to Canada’s growth and expansion.

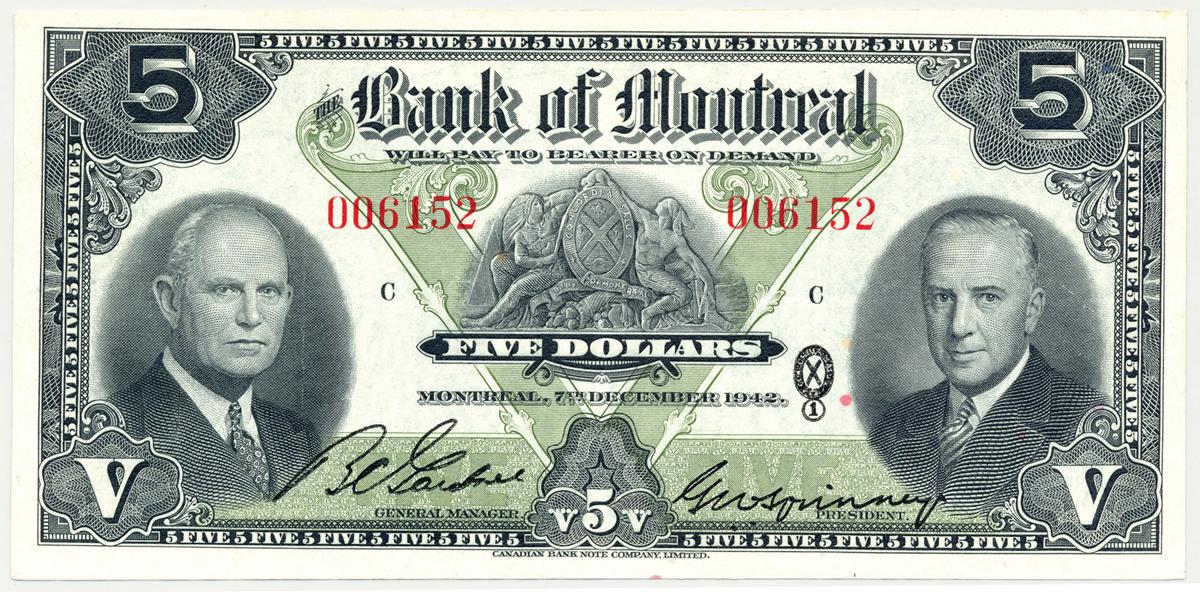

Barely opened in 1817 in a very modest office in downtown Montreal, it issued the first Canadian paper currency in the same year. The $20 note promised to pay the bearer on demand the face value in gold or silver.

Later, other banks would come and go issuing competing scrip, including the Molson’s Bank, complete with engraved likenesses of Peter and Thomas Molson. But the Bank of Montreal had the preferred currency, issuing its last note pictured right, in 1942.

Foremost among the original nine men who signed the Articles of Association of the bank was John Richardson, a merchant who arrived from America in 1787 and was heavily involved in what still was the commercial core of business in the new British colony, the fur trade.

He was a partner in the North West Company, the arch rival of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Like so many bank leaders in years to follow Richardson was active in politics, serving two terms in the Legislature of Lower Canada. There were no conflict of interest rules in those days.

With the decline in the fur trade, John Molson reinvented and expanded the bank’s commercial activities. Edwin King became president in 1869, securing the bank as the most important financial institution in Canada with ruthless focus.

With the decline in the fur trade, John Molson reinvented and expanded the bank’s commercial activities. Edwin King became president in 1869, securing the bank as the most important financial institution in Canada with ruthless focus.

He established close ties to the new government of Canada as its banker. He so incurred the wrath of Toronto capitalists with his aggressive methods that a director, Senator William McMaster, resigned and founded the Canadian Bank of Commerce. During the US civil war the bank became the go-to bank in the New York Gold market.

After confederation, relations with Sir John A. Macdonald were especially close. Due to its capabilities and capital, and strong presence in London and New York, it represented the new Dominion in those markets. As the senior bank, it acted as co-ordinator-in-chief of the whole system. In many ways, it was “Canada’s banker.”

But the most renowned and influential president was Donald Smith.

He was a former officer of the Hudson’s Bay Company and became president in 1887. He was a key participant in the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway, which was heavily financed by the bank. Smith was a founding partner in what was later to become Bell telephone. He too buttressed the bank’s influence by sitting in the House of Commons several times. Such was his vast wealth that he spent $1 million raising and equipping an entire regiment to fight in the Boer War.

The depression and its aftermath marked the finale for Bank of Montreal’s almost complete dominance of the financial industry. Following a Royal Commission, and lobbying by the Royal Bank displeased with its rival’s position, the government opened a new central bank in 1935, the Bank of Canada "to regulate credit and currency in the best interests of the economic life of the nation." Even the private banks’ gold holdings were transferred to the central bank.

The bank was important to Ottawa long before Bytown became the capital. It opened its first branch in Ottawa 1840, and became active in financing the wood and lumber trade.

Its close relationship with the new Canadian government after 1867 made new premises necessary. A lot at the corner of Wellington and O’Connor was bought and an ever-expanding home was built.

In 1929 an elegant building was constructed at Wellington and Sparks, with an impressive banking hall described in an architectural journal as “a traditional temple bank in modernistic disguise." Today, this is the Sir John A. Macdonald building owned by the government of Canada.

The huge historic head office building in Montreal is still “the largest and architecturally the most monumental banks building in the world.”

Elsewhere the bank’s physical footprint has changed dramatically. Its former Toronto head office, the beautiful Beaux Arts edifice on Yonge Street is now the Hockey Hall of Fame.

Now First Canadian Place is the towering focus of it national and international operations.

Just as it was with the CPR, the bank continued in the late 1960s and '70s under president W.D. Mulhulland to be the major financer of mega-projects, this time in hydro electric energy.

The bank led the financing at the time for Churchill Falls, the largest hydro development on the continent – which was inaugurated in 1967. The biggest corporate loan in Canadian history came a few years later when the bank extended $1.25 billion to Hydro Quebec for the building of Phase I of the James Bay project.

Among the many gems illuminating the bank’s long history is that up until the last generation, managers had a pistol as standard issue. Handling revolvers was as commonplace as counting money. One story relates an attempted hold-up at Bloor and Bay streets in Toronto that was stopped dead by the manager waving his pistol.

Clearly, the Canadian banks have left a big footprint on the history of Canadian business and politics.